Cache Coherence Problem

Cache Coherence Issue

The cache coherence problem arises in multi-core or multiprocessor systems where each processor has its own local cache, and all processors share the same main memory. This situation creates the possibility of inconsistent views of memory across caches, leading to incorrect program behavior.

When multiple processors access and modify shared data, the cached copies may become out of sync. Ensuring that all caches reflect the most recent and consistent value of shared data is the essence of the cache coherence problem.

Causes:

- Multiple Copies of Data: Each processor may cache a copy of the same memory location. If one processor updates its copy, others may still use outdated versions.

- Write-Back Policies: In write-back caching, modifications are not immediately written to the main memory, increasing the risk of stale data in other caches.

- Concurrent Access: Simultaneous reads and writes to the same memory location by multiple processors can lead to inconsistencies.

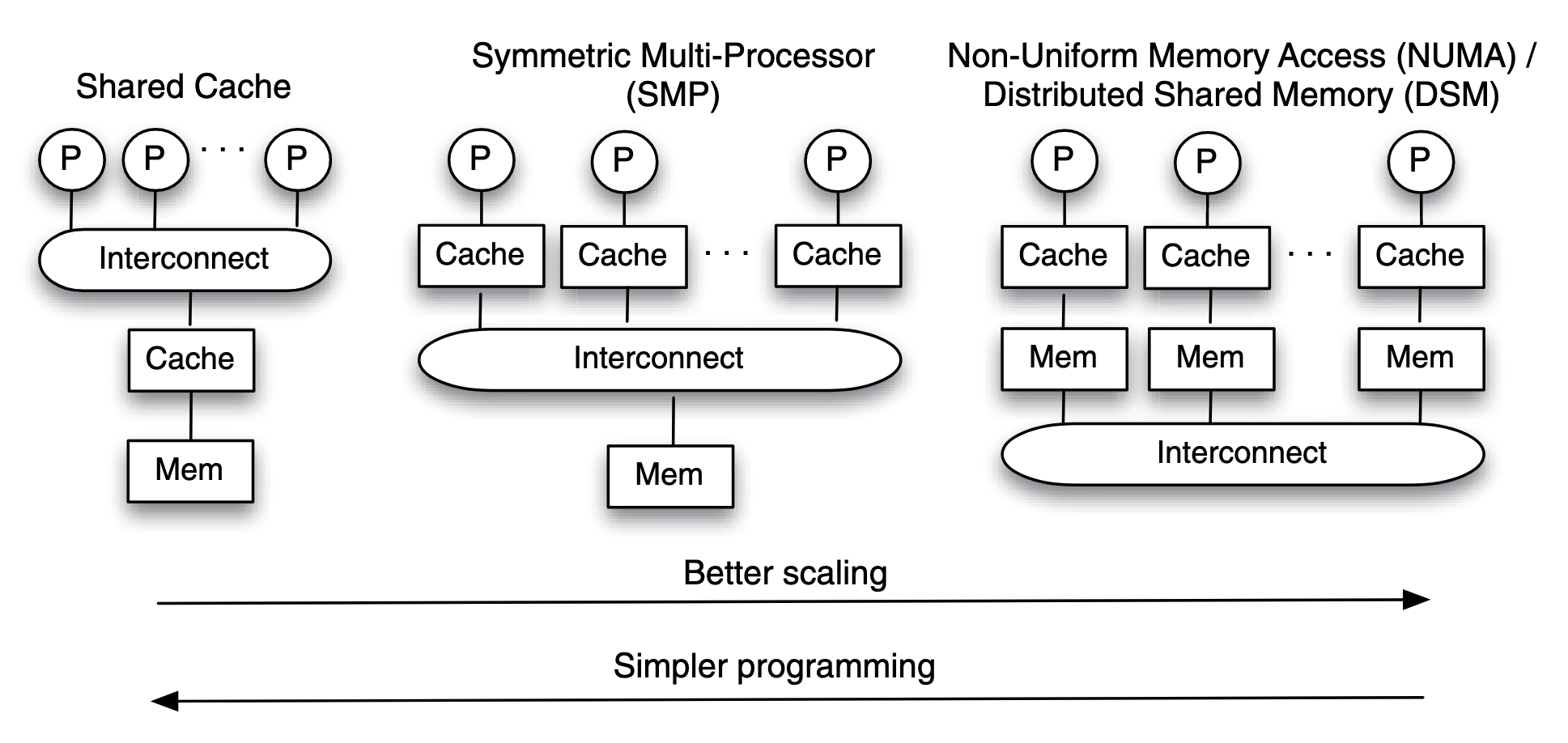

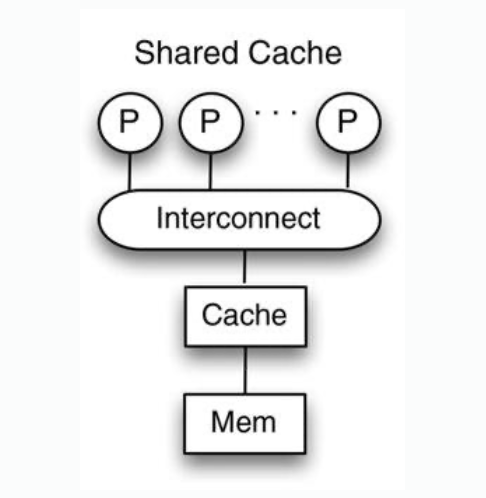

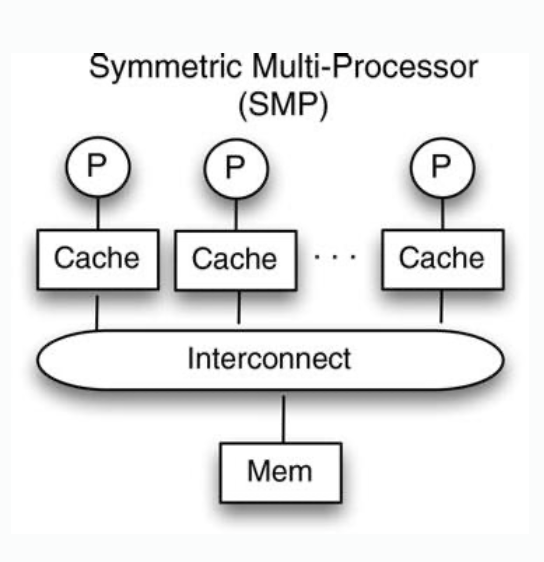

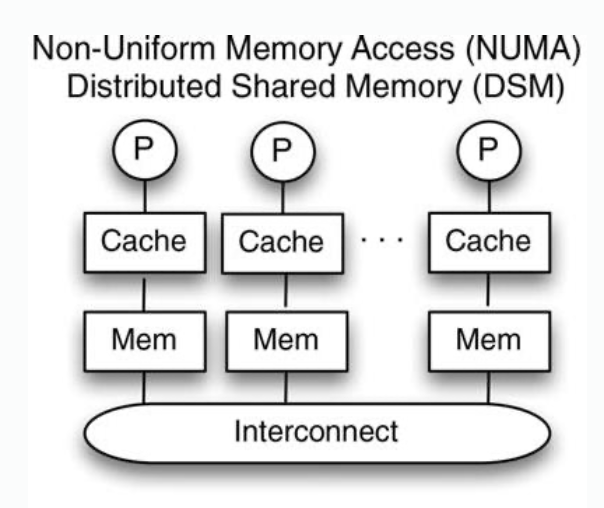

Figure: three different ways that multi-processors are connected. They differ in the level of the memory hierarchy they are interconnected at, and what interconnection is used.

Compared to shared cache system, symmetric multi-processor architecture allows better scaling, and a fast cache access time to the local cache, but the programming will be more complex due to the need for data locality in caches. Distributed shared memory in which memories are interconnected, is the most scalable.

An increase in the access time to main memory makes a smaller impact on the overall performance than the same amount of increase in the access time to caches. Adding extra few tens or hundreds of nanoseconds in latency to access remote memories only increase the overall latency by less than an order of magnitude. In contrast, adding tens to hundreds of nanoseconds to the access time of some segments of the cache that are remote will significantly reduce the overall cache performance.

| Which | Shared Cache | Symmetric Multi-Processor | Distributed Memory Access |

|---|---|---|---|

| Figure |  |  |  |

| Coherence situation | Cache coherence in shared cache architecture is automatically achieved. Only one copy of a cache block exists. | Coherence problems exist caused by reads and writes of the same address issued by different processors | |

| Disadvantages | Not scalable. Distance to cache. Access latency of cache increases as number of cores increases. | ||

| Note | Heavy load on interconnection | Reduced pressure on interconnect, only cache misses. | Reduced pressure on interconnect, some misses handled by local memory. |

Does interconnect support broadcast/snooping in symmetric multi-processor system?

For a multi-processor system, two requirements maintaining cache coherence are:

- Write propagation: propagate changes in one cache to other caches, namely, the requirement.

- Transaction serialization: multiple operations (reads or writes) to a single memory location are seen in the same order by all processors.

Write through policy (see Lecture - Memory Hierarchy) is not a solution for write propagation, in the worst case variable x is stored in memory, cache of processor and cache of processor , any changes to x made by processor will also be updated back to memory, but not updated in cache of processor . The problem still exists.

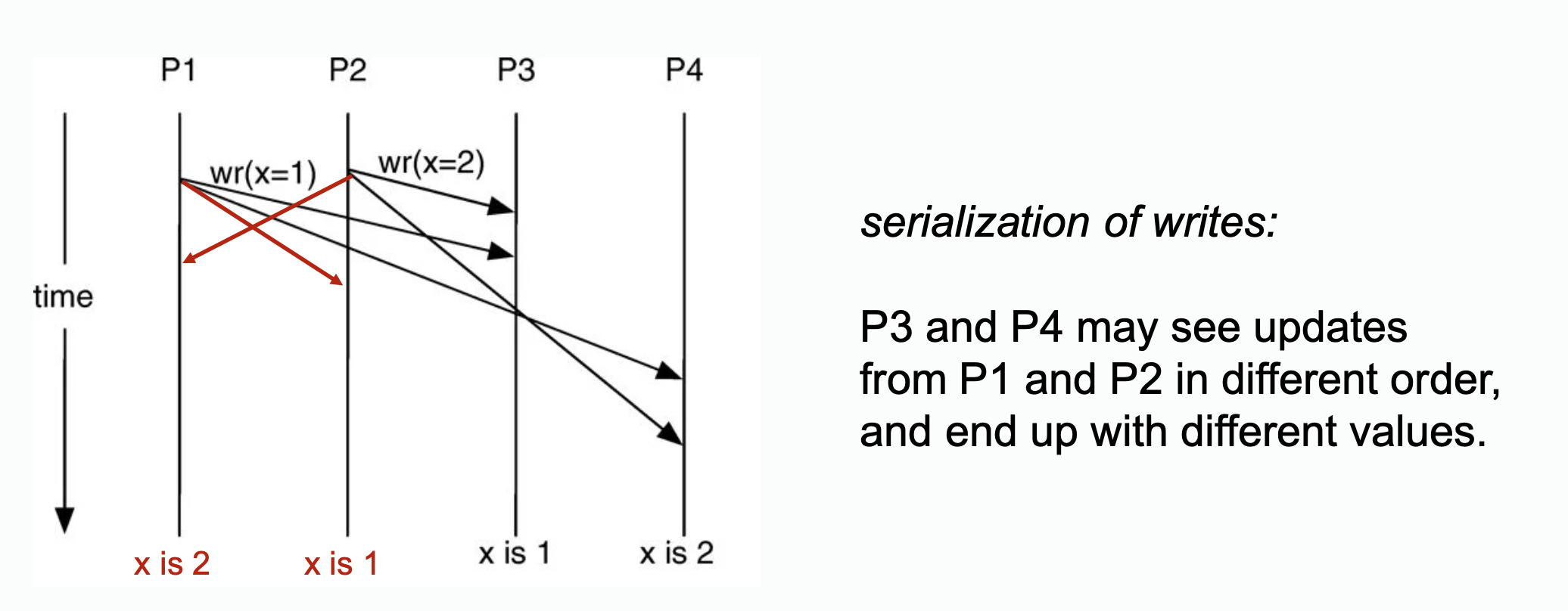

We often refer to a write operation as a write transaction and a read operation as a read transaction, implying that each operation has to be atomic with respect to one another. Note, however, that serialization between two read operations is not required because in the absence of writes, as long as the value is coherent initially, the reads will return the same value. Serialization between writes, as well as serialization between reads and writes, are required in order for all processors to have a coherent view of cached values.

Example without transaction serialization

>

>  Figure: need for transaction serialization between writes (a) and between a write and a read (b).

Figure: need for transaction serialization between writes (a) and between a write and a read (b).

Cache Coherence in Bus-Based Multiprocessors

Please refer to Lecture - Cache Coherence in Bus-based Multiprocessors

Coherence without a Bus: Broadcast Protocol with Point-to-Point Interconnect

The basic requirements of coherence protocol are:

- Write propagation: broadcast and snoop

- Transaction serialization: some components must serve as the ordering point. In bus based systems, its a bus; while in none-centralized system, a sequencer is required.

For a medium-scale multiprocessor system, a suitable alternative is to use point-to-point interconnection, while still relying on a broadcast or snoopy protocol. To implement snoopy coherence protocols in systems without a centralized bus interconnect, we need to address the challenge of enabling caches to observe memory transactions initiated by other processors.

Transaction serialization requires two things:

- a way to determine the sequence of transactions that is consistently viewed by all processors

- a way to provide the illusion that each transaction appears to proceed atomically, absence of overlap with other transactions.

Sequencer

Globally sequencing requests is more challenging due to the absence of a natural sequencer since there is no shared medium such as the bus.

- The first approach is to assign a sequencer whose role is to provide an ordering point for colliding requests and ensuring that requests are processed and seen by all cores in that order.

The second approach is to design the protocol to work in a distributed fashion, without having to assign a single sequencer.(this is not required by CSC506)

Here we use the first approach, all requests are sent to the sequencer, and the order in which they are received by the sequencer determines the order in which the requests are serviced. The same order must also be the same one observed by all processors.:

- A write request that arrives at the sequencer is handled by broadcasting an invalidation to all processors, which respond by sending an invalidation acknowledgment message to the sequencer or the requester (this is a design choice).

- A read request that arrives at the sequencer will also be broadcast to all processors, so that it can be determined where the block may be cached. If a cache holds the block in a dirty state, it will supply the block. When the requester obtains the block, it sends acknowledgment to the sequencer, which then considers the request processing complete.

- During the time request processing has started but has not completed, new requests that arrive at the sequencer will be rejected or serviced at a later time when the current request is complete.

This approach locks up the sequencer for the block address until the current request is fully processed. Such an approach reduces concurrency for request processing, but may be acceptable if the number of caches is relatively small.

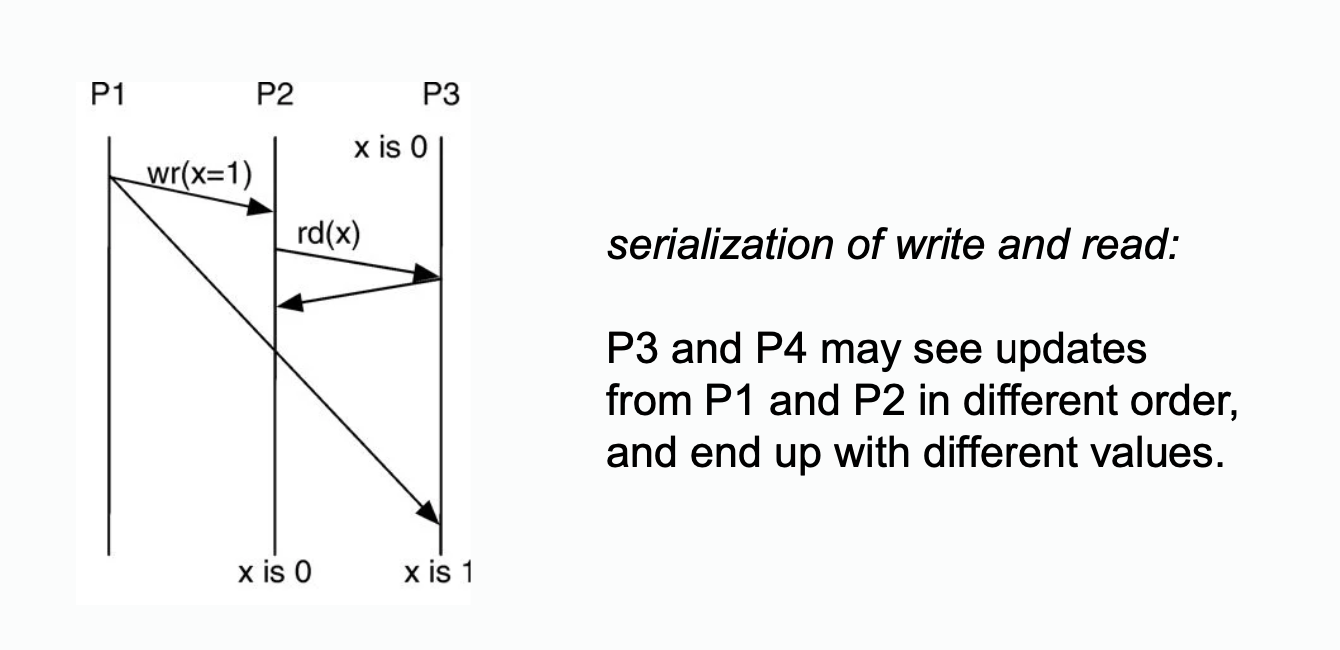

Example: 6-node system P2P interconnected, simultaneous write

Assume each node to have a processor/core and a cache. Now suppose that node A and B simultaneously want to write to a block that they already cached in a clean state. Suppose that node S is assigned the role of sequencing requests for the block.

Suppose that the request from node A arrives at node S before the request from node B. Here is what happens:

- (b) A and B sent

Upgrto S. - (c) S needs to ensure that the write by A is seen by all cores as happening before the write by B. To achieve that, S serves the request from A, but replies to B with a negative acknowledgment (

Nack) so B can retry its request at a later time. - (c) To process the write request from A, S can broadcast an invalidation (

Inv) message to all nodes as shown in part. - (d) All nodes receive the invalidation message, invalidate the copy of the block if the block is found in the local cache, and send invalidation acknowledgment (

InvAck) to node A. - (e) After receiving all invalidation acknowledgement messages, A knows it is safe to transition the block state to modifed, and to write to the block. It then sends a notice of completion to the sequencer S

- (f) Upon S receiving the notice from A, the sequencer knows the write by A is completed, it then proceed next to the request from B.

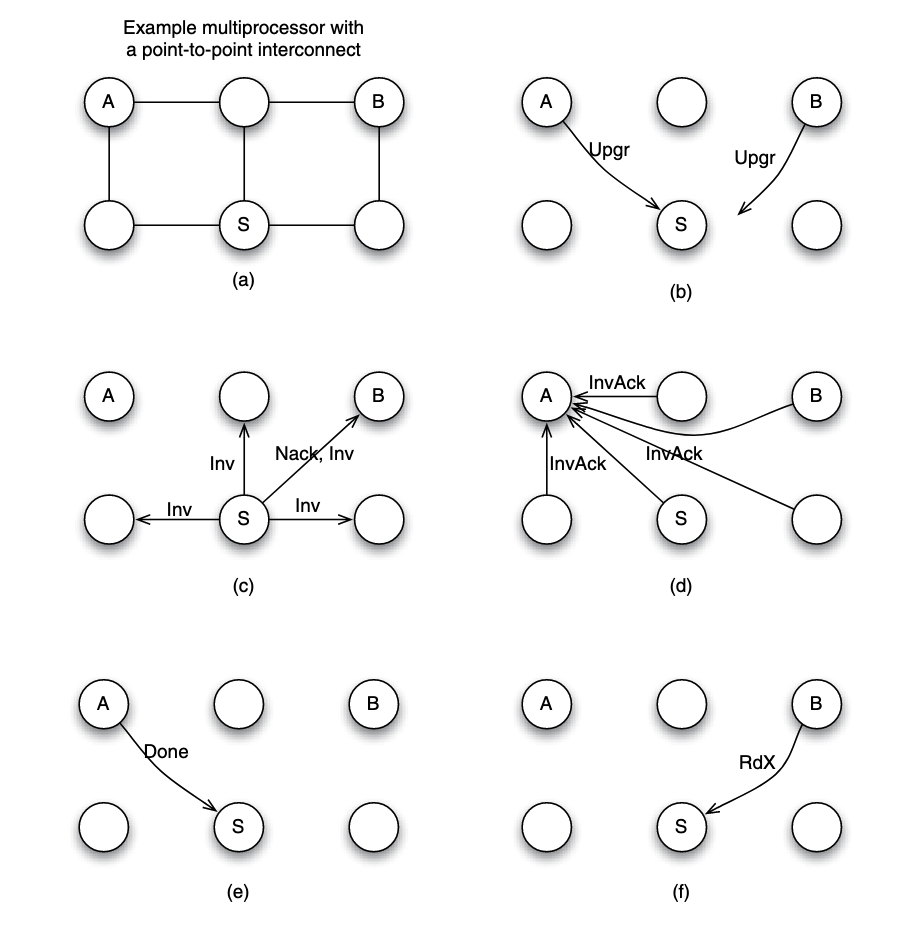

Example: 6-node system P2P interconnected, simultaneous read

Suppose that node A and B simultaneously want to read to a block that they do not fnd in their local caches. This situation is unique since it does not involve a write request, therefore we are not dealing with two different versions (or values) for the data block. Thus, it is possible to overlap the processing of the two requests.

- (a) Both node A and B send the read request to node S. Suppose that request from node A arrives earlier in node S, and hence it is served first by S. The sequencer S can mark the block to indicate that the read has not completed.

- (b) S does not know if the block is currently cached or not, or which cache may have the block. So it has to send an intervention message to all nodes (except the requester A), inquiring if any of them has the data block.

- (c) Suppose that node C has the block and supplies the block to A, while other nodes reply with NoData message to A.

- (d) In the mean time, let us suppose that the sequencer receives a new read request by node B. Since this is a read request, the sequencer can overlap the processing safely, without waiting for the completion of the outstanding transaction. It sends intervention message to all nodes except the requester B.

- (e) Nodes A and C have a copy of the block, and hence both may send the data block to node B.

Directory Coherence Protocol

Please refer to Lecture - Directory Coherence Protocol