Consistency and Synchronization Problems

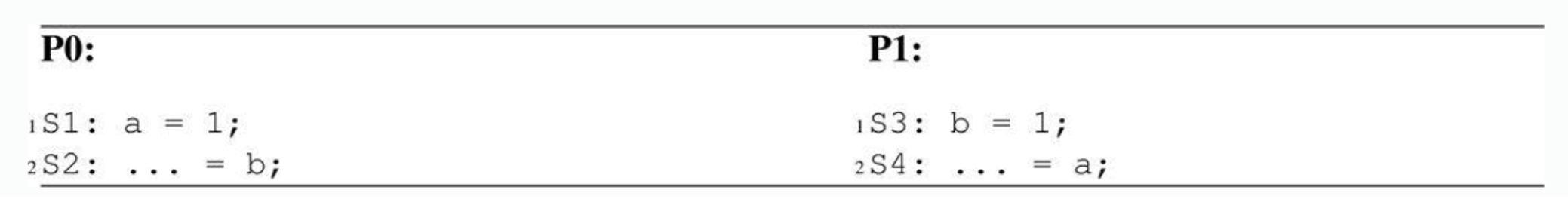

Whereas the cache coherence determines the requirement for propagating a change of value in a single address in one cache to other caches and the serialization of those changes, the memory consistency deals with the ordering of all memory operations (loads and stores) to different memory locations.

Familiar consistency models:

- Sequential Consistency is the strongest consistency that ensures all memory operations appear to execute in a single, global order called program order, and each of the memory operation should be performed atomically.

- Weak Consistency (related to barrier) divides operations into synchronization and data operations. It ensures consistency only at synchronization points. It's faster than sequential consistency but requires explicit synchronization.

- Release Consistency (related to critical section) extends weak consistency by splitting synchronization into acquire (before critical section) and release (after critical section). It provides finer-grained control over memory synchronization, improving performance. It only ensures consistency only between acquire and release operations.

Mutual Exclusion

Mutual exclusion requires that when there are multiple threads, only one thread is allowed in the critical section at any time.

Mutual exclusion is not a problem that is unique to multiprocessor systems. In a single processor system, for example, multiple threads may time-share a processor, and accesses to variables that are potentially modified by more than one thread must be protected in a critical section.

In single core: disabling all interrupts ensure that the thread that is executing will not be context switched or interrupted by the OS. This is costly. In multi-core: disabling interrupts does not achieve mutual exclusion because other threads in different processors still execute simultaneously.

What is a spin lock: It is a lock that causes a thread trying to acquire it to simply wait in a loop ("spin") while repeatedly checking whether the lock is available.

Program Order and Sequential Consistency

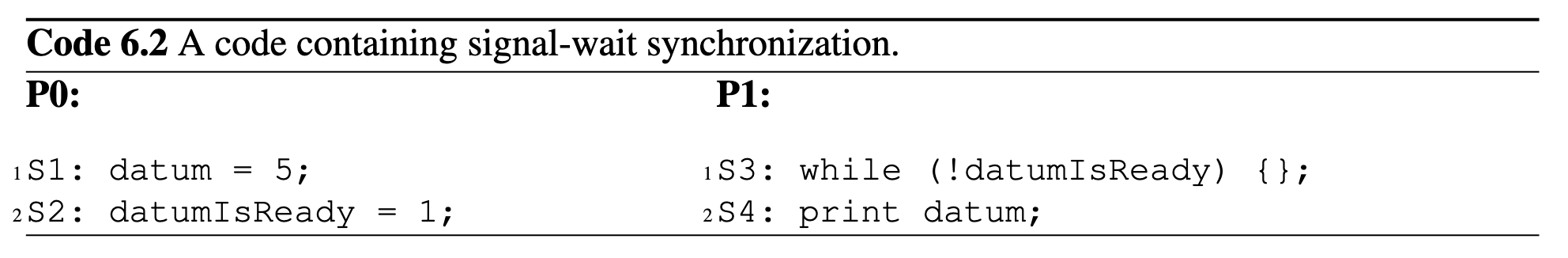

A simple example for this requirement is point-to-point(a.k.a. producer-consumer) shared memory program. Producer-Consumer (Events, Post-Wait) coordinates execution between threads where one (the producer) generates data, and another (the consumer) processes it. Synchronization ensures proper sequencing between production and consumption.

Producer-Consumer-style synchronization

P1 wait for thread P0 to pass some value to it through the memory:

In the above example, if the wait is achieved by a while loop as shown in code above, this can be incorrect because S2 may happen before S1, because in that case P1 will continue to print datum before it has the value 5.

Concept: Program Order S1 should happen before S2 as it is logically written in your program is called program order.

In C language, if a variable is marked as volatile, the compiler will ensure the sequence order of different access to this variable.

Another problem here is that S2 may propagates faster than S1, and P1 will first see S2's value than S1.

The two problems mentioned above, S2 may happen before S1, and S2 may propagates faster than S1, are memory consistency problems. The consistency deal with the ordering of all memory operations to different memory locations.

The strongest consistency is Sequential Consistency model, it guarantees that all loads/stores are the same as the sequential execution of the program.

Different Types of Synchronization

- Mutual exclusion: Ensures that only one thread or process can access a critical section (shared resource or code block) at any given time, preventing data races or inconsistencies.

- Producer-Consumer (Events, Post-Wait): Coordinates execution between threads where one (the producer) generates data, and another (the consumer) processes it. Synchronization ensures proper sequencing between production and consumption.

- Events (Signaling): A thread (producer) signals the consumer thread to wake up and consume the data.

- Post-Wait (Semaphores): Producer “posts” (increments) a semaphore to indicate data is ready; consumer “waits” (decrements) the semaphore before consuming.

- Barrier: Ensures that all threads or processes in a parallel program reach a specific point of execution (the barrier) before any of them proceeds. This synchronizes threads to a common point in the program.

| Type | Purpose | Key Mechanisms | Example Use Cases |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mutual Exclusion | Prevent simultaneous access to shared resources. | Locks, Mutexes, Semaphores | Accessing shared counters, file operations. |

| Producer-Consumer | Synchronize production and consumption of data. | Events (Condition Variables), Post-Wait, Buffers | Task queues, data pipelines. |

| Barrier | Synchronize threads at a common execution point. | Centralized counters, Sense Reversal, Messages | Iterative algorithms, phase synchronization. |

Software Based Consistency

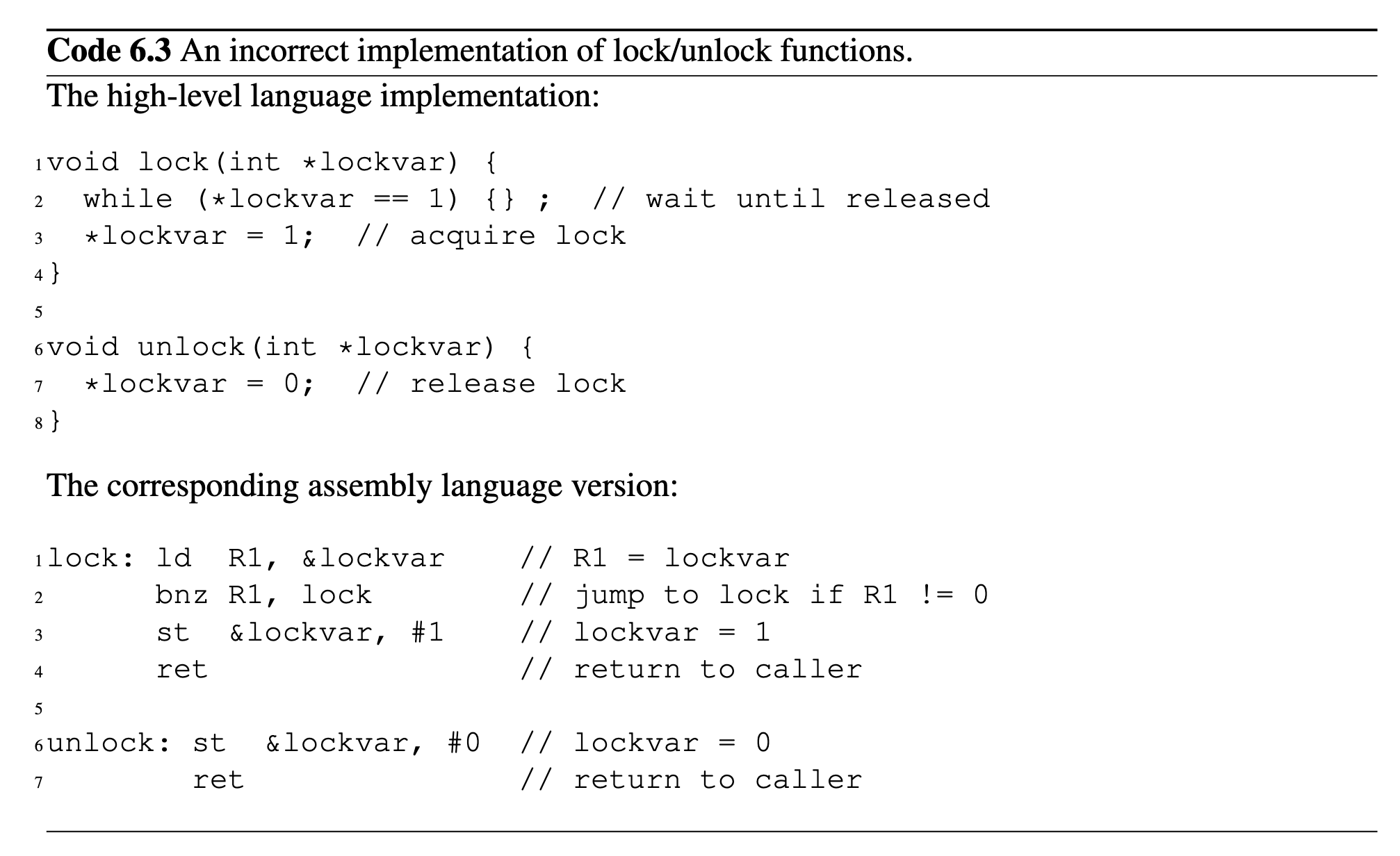

Naive software approach does not work,

⬇️

There is a software approach "Peterson’s algorithm" can deal with dual-thread situation, but gets much more complicated when there are more threads. Hardware support is much more simpler than that.

Naive software approach does not work,

⬇️

There is a software approach "Peterson’s algorithm" can deal with dual-thread situation, but gets much more complicated when there are more threads. Hardware support is much more simpler than that.

Metrics and Overheads in Consistency Model

- Scalability: how synchronization latency and bandwidth scale with a larger number of threads

- Contended latency: the time it takes to obtain a lock that will fail(because someone else is using the lock)

- Lock-acquisition latency: the time it takes to obtain a lock

- Uncontended latency(related lock-acquisition latency?): the latency when threads do not simultaneously try to perform the synchronization

Atomic Instructions

Concept: Atomic Instruction Atomic instruction implies that (1) either the whole sequence is executed entirely, or none of it appears to have executed. (2) only one such instruction from any processor can be executed at any given time.

For commonly used atomic instructions, consider register Rx and Ry, and memory location M, common atomic instruction includes:

test-and-set Rx, M: read from M, test to see if it matches some specific value(such as 0), and set it to some value.fetch-and-op M: read M, do increment, decrement, addition, subtraction on M, and write it back.exchange Rx, M: exchange the value in memory location M and value in register Rxcompare-and-swap Rx, Ry, M: compare M with the Rx. If match, write the value in Ry to M, and copy the value in Rx to Ry.

How is atomicity implemented (example in bus based system):

- Instruction is treated as a write , and cache fetches/upgrades the block in M state

- Protocol prevents other access while instruction is in progress.

- Could lock the bus, preventing others from requesting

- Owner (M) can defer responding to other requests, or send NACK t require a retry

Lock Implementations

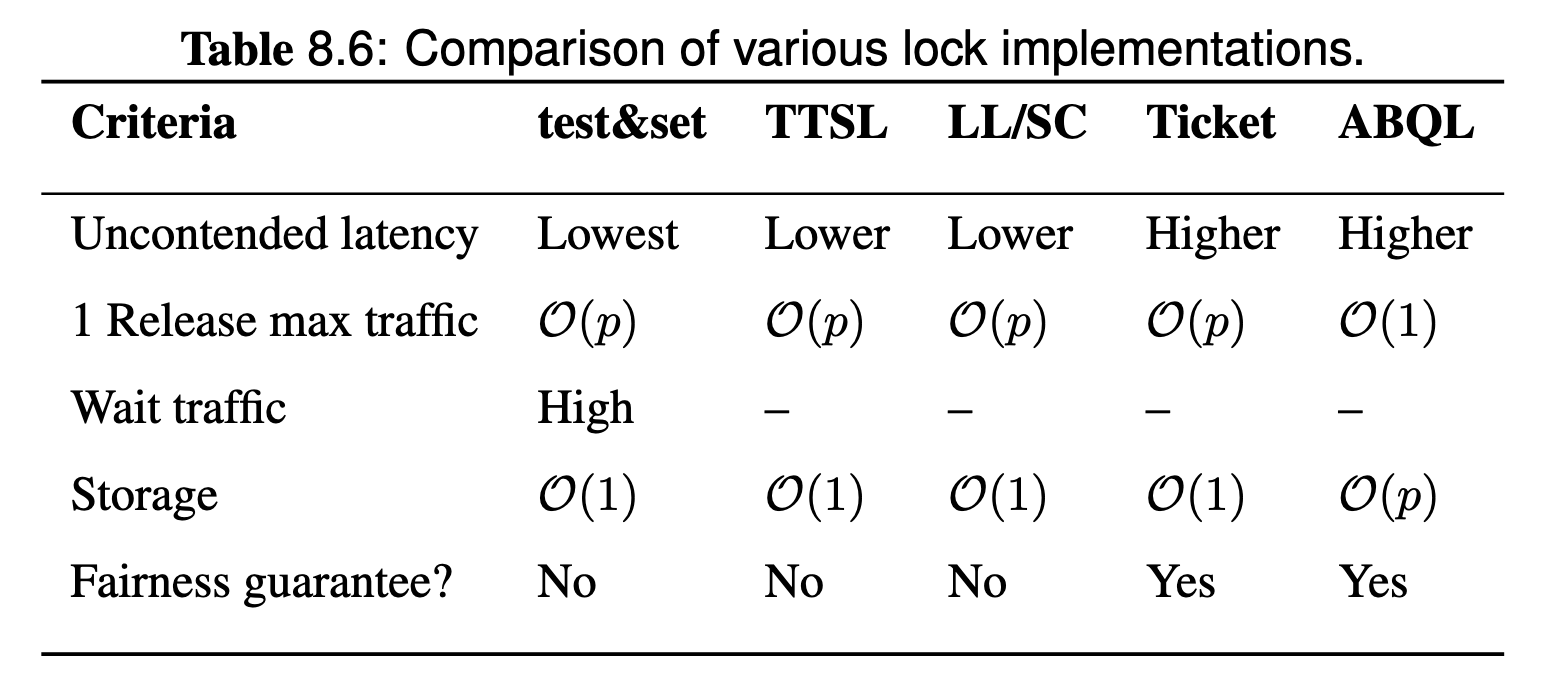

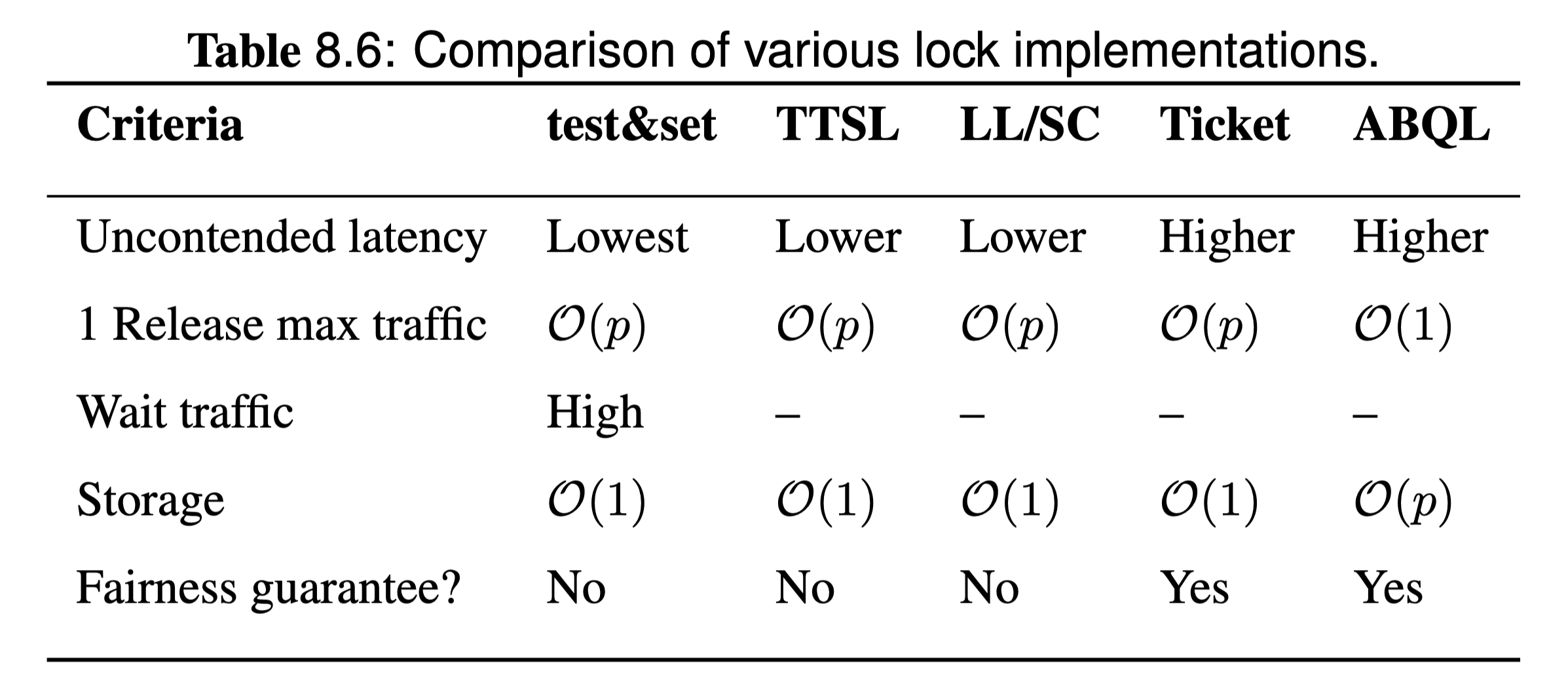

Summary:

- Test and set lock: a basic atomic instruction based lock implementation

- Test and test and set (TTSL): try to reduce

busRdXin test and set - Load linked and store conditional (LL/SC): a lower level primitive and general approach to implement atomic instructions, with different illusion on atomicity. Can be used without bus.

- Ticket Lock: try to introduce fairness in lock acquisition using queue.

- Array-based Querying Lock (ABQL): a improved implementation of ticket lock

I think remember every implementation in detail(how the assembly code looks like) is not the key, understand why these operations must be done as atomic(e.g. test and set) is the key.

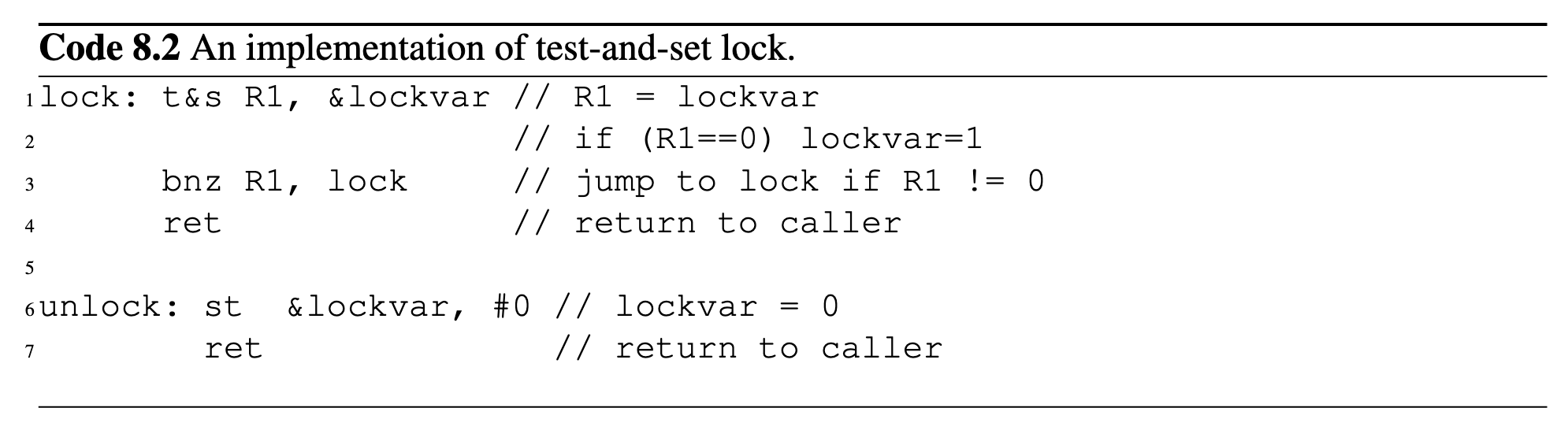

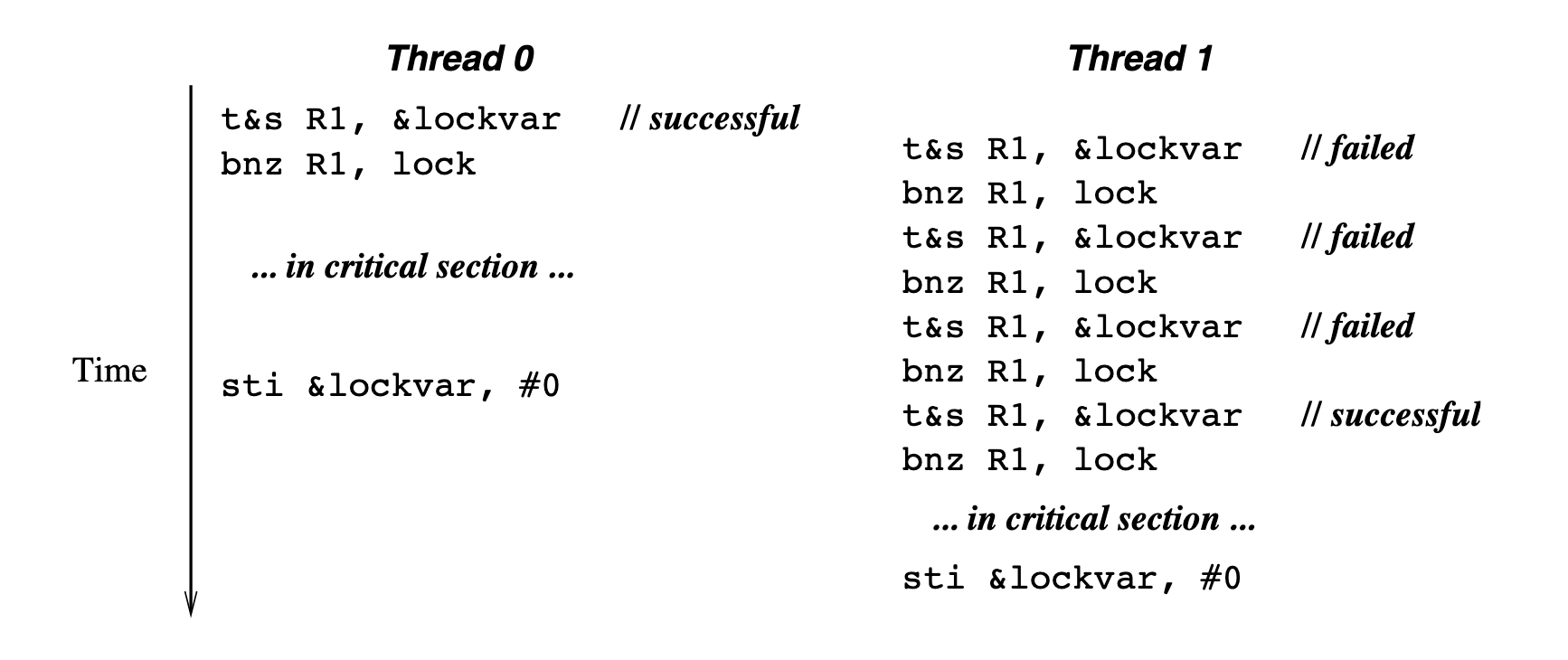

Test-and-set (TSL) Lock

test-and-set Rx, M: an atomic instruction that read from M, test to see if it matches some specific value(such as 0), and set it to some value.

The instruction bnz stands for Branch if Not Zero. The operation of bnz is straightforward: it checks the value of a specified register or memory location, and if the value is not zero, it causes the program to jump to a specified target label or memory address.

Lock:

- A shared variable (e.g.,

lock) is initialized to0(unlocked). - A thread tries to acquire the lock by executing

test-and-set:- If

test-and-set(lock)returns0, the thread acquires the lock (setslock = 1). - If

test-and-set(lock)returns1, the lock is already held, and the thread keeps trying (spinning). Unlock:

- If

- The thread that holds the lock resets

lockto0, allowing other threads to acquire it.

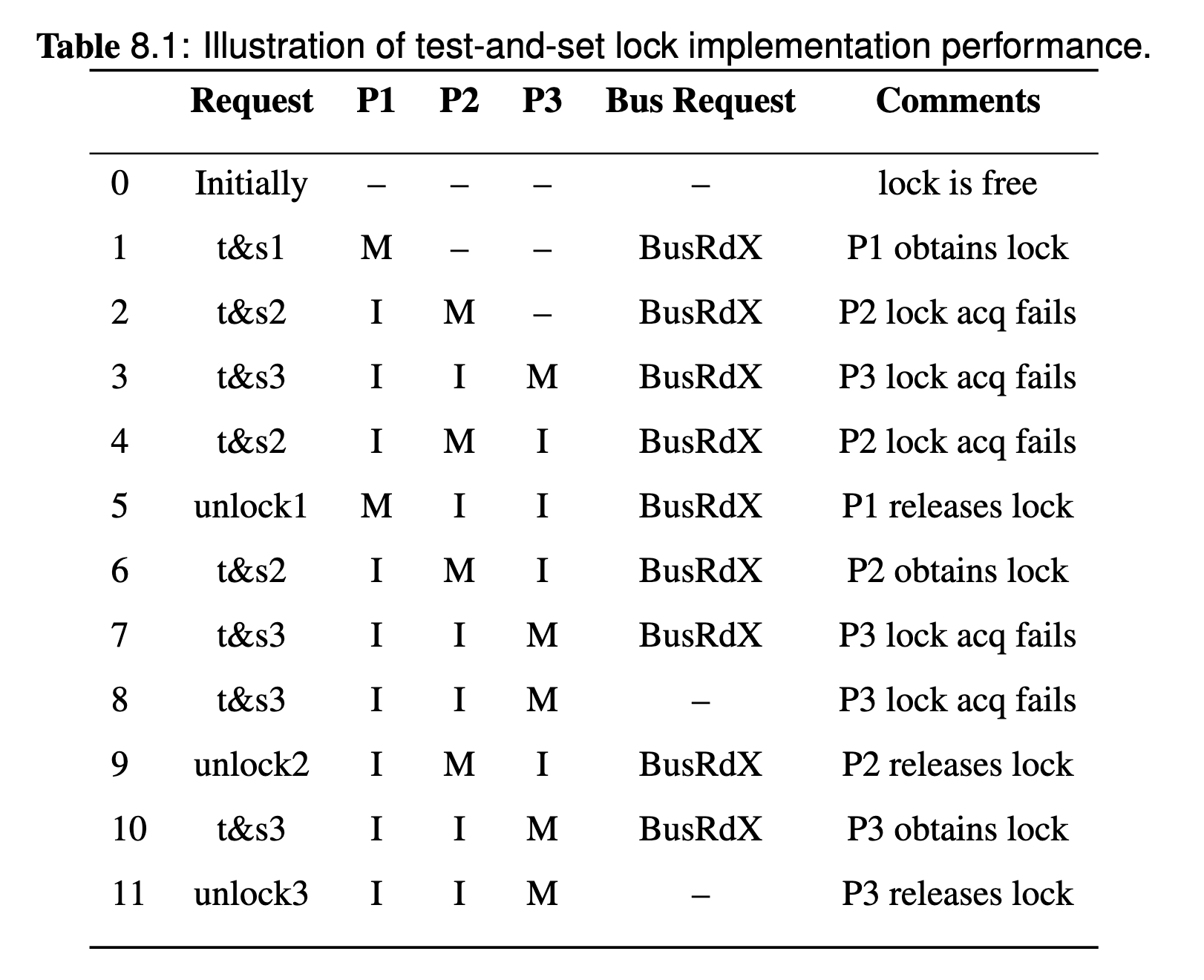

[!CAUTION] Problems of test-and-set lock

- Bus traffic: high when contending for the lock

- Fairness: all processors have an equal chance (assuming a global bus)

- Efficiency: starvation can occur

Regarding the bus traffic, the problem is because each lock acquisition attempt causes invalidation of all cached copies, regardless of whether the acquisition is successful or not:

Assume there are 3 threads competing for this lock, the memory coherence and state changes will looks like:

Why it is a BusRdX?

According to the example, whether the acquisition is successful or not, the bus request is a BusRdX since the atomic test-and-set will try to write(if lock obtain success) after the read.

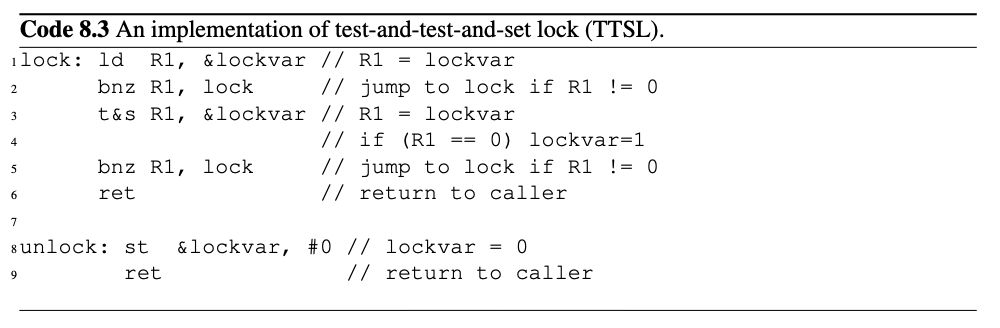

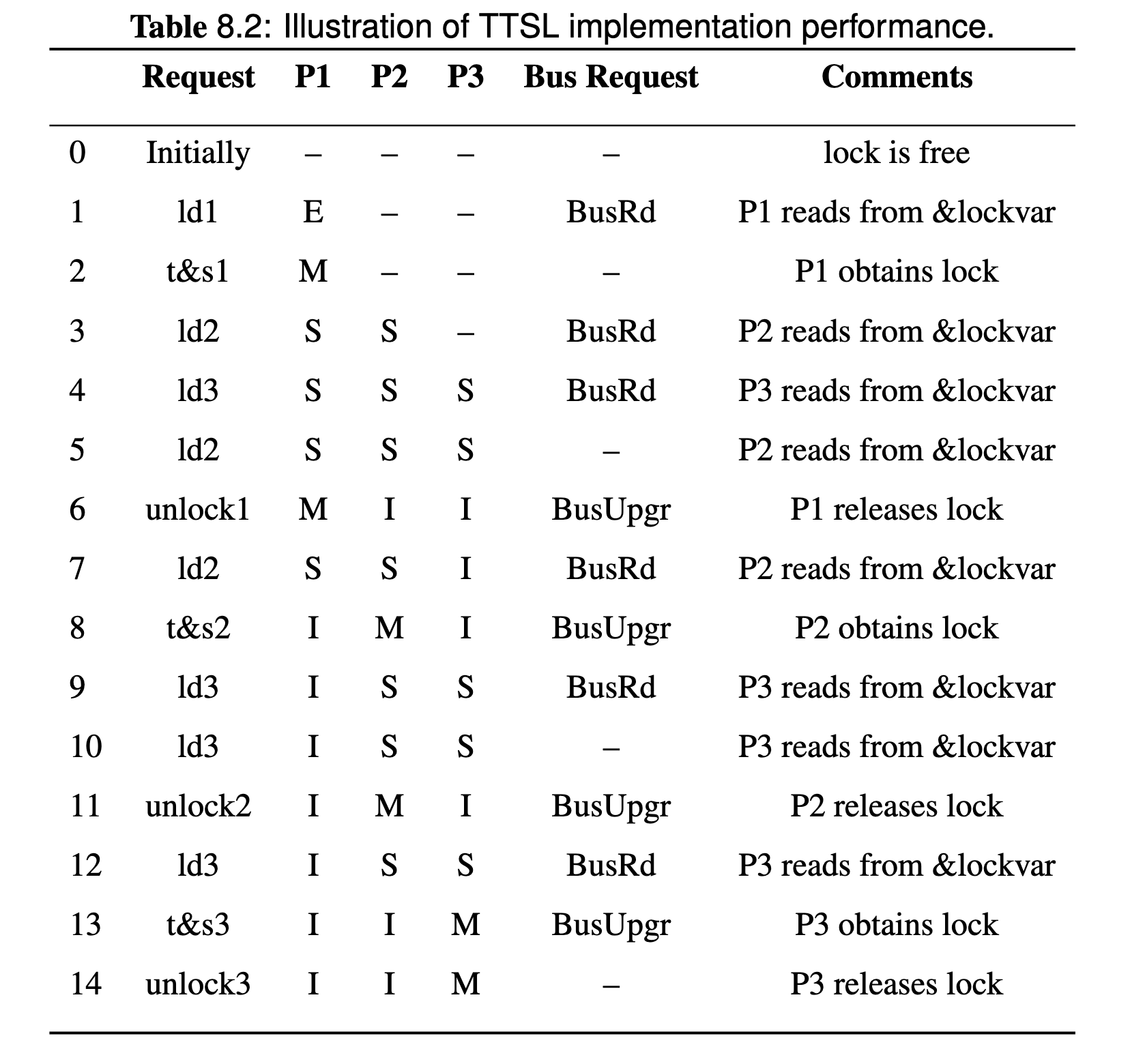

Test-and-test-and-set (TTSL) Lock

TTSL is an improvement over the test-and-set lock implementation on traffic problem. Recall that in test-and-set lock, there is a bus traffic problem. to reduce the traffic requirement is to have a criterion that tests whether a lock acquisition attempt will likely lead to failure, and if that is the case, we defer the execution of the atomic instruction. Only when a lock acquisition attempt has a good chance of succeeding do we attempt the execution of the atomic instruction.

t&s refers to regular test-and-set lock. TTSL has:

- advantage: significantly reduce bus traffic by replacing

BusRdXwithBusRdin contending situation. - disadvantage: uncontended latency is higher than

test-and-setlock caused by one more load and branch instruction.

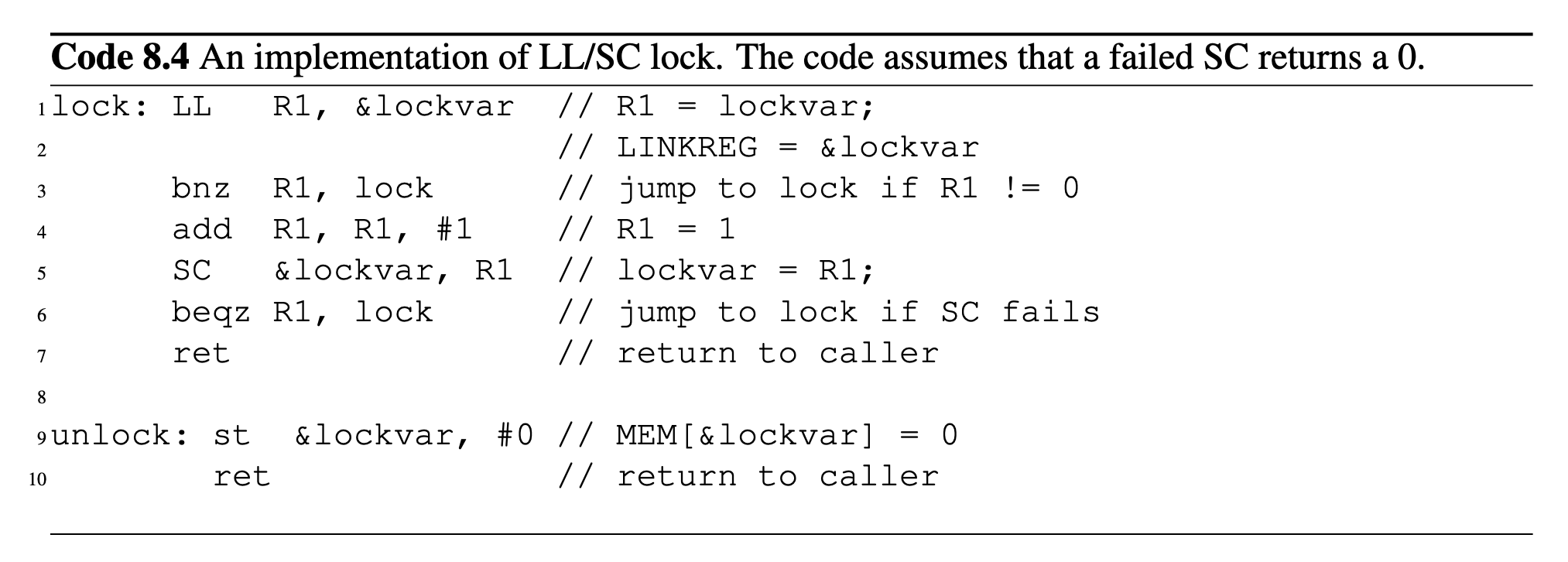

Load Linked and Store Conditional Lock (LL/SC)

The TS(test-and-set) lock and its improved implementation TTS(test-and-test-and-set) lock are both for bus based systems. Two problems exists because one way to implement an atomic instruction requires a separate bus line that is asserted when a processor is executing an atomic instruction. Bus based approaches are:

- not general enough as they only work for bus based systems.

- inefficient if the lock access frequency is high. Each lock acquisition and release causes the bus to be occupied by one processor at a time, which introduces bottlenecks.

- Unnecessary serialization exists when their are multiple access to different locks. Each lock acquisition occupies the bus, even if different locks are accessed and each of them uses separate bus lines, only one of them can access the bus at the same time.

Load Linked and Store Conditional Lock introduces another perspective of illusion of atomicity and can achieve atomicity without special bus line. Iit does not assume the existence of a special bus line so it can work with other interconnects as well

Illusion of Atomicity An illusion of atomicity can be built on a sequence of instructions, which means either none or all of the instructions appear to have executed, or it can be built on true instruction atomicity, that is a hardware level atomicity.

From the first point of view, the lock acquisition essentially consists of:

- load (

ld,R1, &lockvar) - conditional branch (

bnz, R1, lock) - store (

st &lockvar, R1)

But only store is logically visible to other processors (for example, because it causes a BusWr that broadcast to other processors). Therefore, the instruction that is critical to the illusion of atomicity is the store instruction. If it is executed, its effect is visible to other processors. If it is not executed, its effect is not visible to other processors.

Load Locked (a.k.a. Load Linked) The load that requires a block address to be monitored from being stolen (i.e., invalidated) is known as a load linked or load locked (LL). The LL/SC pair turns out to be a very powerful mechanism on which many different atomic operations can be built. The pair ensures the illusion of atomicity without requiring an exclusive ownership of a cache block.

Store Conditional (SC)

In order to give the illusion of atomicity to the sequence of instructions, we need to ensure that the store fails (or gets canceled) if between the load and the store, something has happened that potentially violates the illusion of atomicity (for example, context switch, a busRdX, a Flush or something like that).

If, however, the block remains valid in the cache by the time the store executes, then the entire load-branch-store sequence can appear to have executed atomically. The illusion of atomicity requires that the store instruction is executed conditionally upon detected events that may break the illusion of atomicity. Such a store is well known as a store conditional (SC).

A special processor register called linked register is used to monitor a block address from being stolen. The linked register will clear and SC will fail when:

- Another processor has raced past it, successfully performed an SC, and stolen the cache block

- Context switch happens

As an example:

- If a read happens during this procedure, that is, it snooped a

BusRdon the same address, nothing will happen on this lock, the linked register will not clear - But if a

BusWror something cause the cache to be invalid, the lock will fail and the linked register will clear.

So the key to identify if some snooped bus behavior will cause a fail on the lock, check if the action will invalidate the cache state.

For the implementation, bezq provides a jump if SC fails:

If it fails, the store will not happen, and rest of the system cannot see the store and will not even know if it happened. If it is success, other processors will know because the store propagate to the rest of the system.

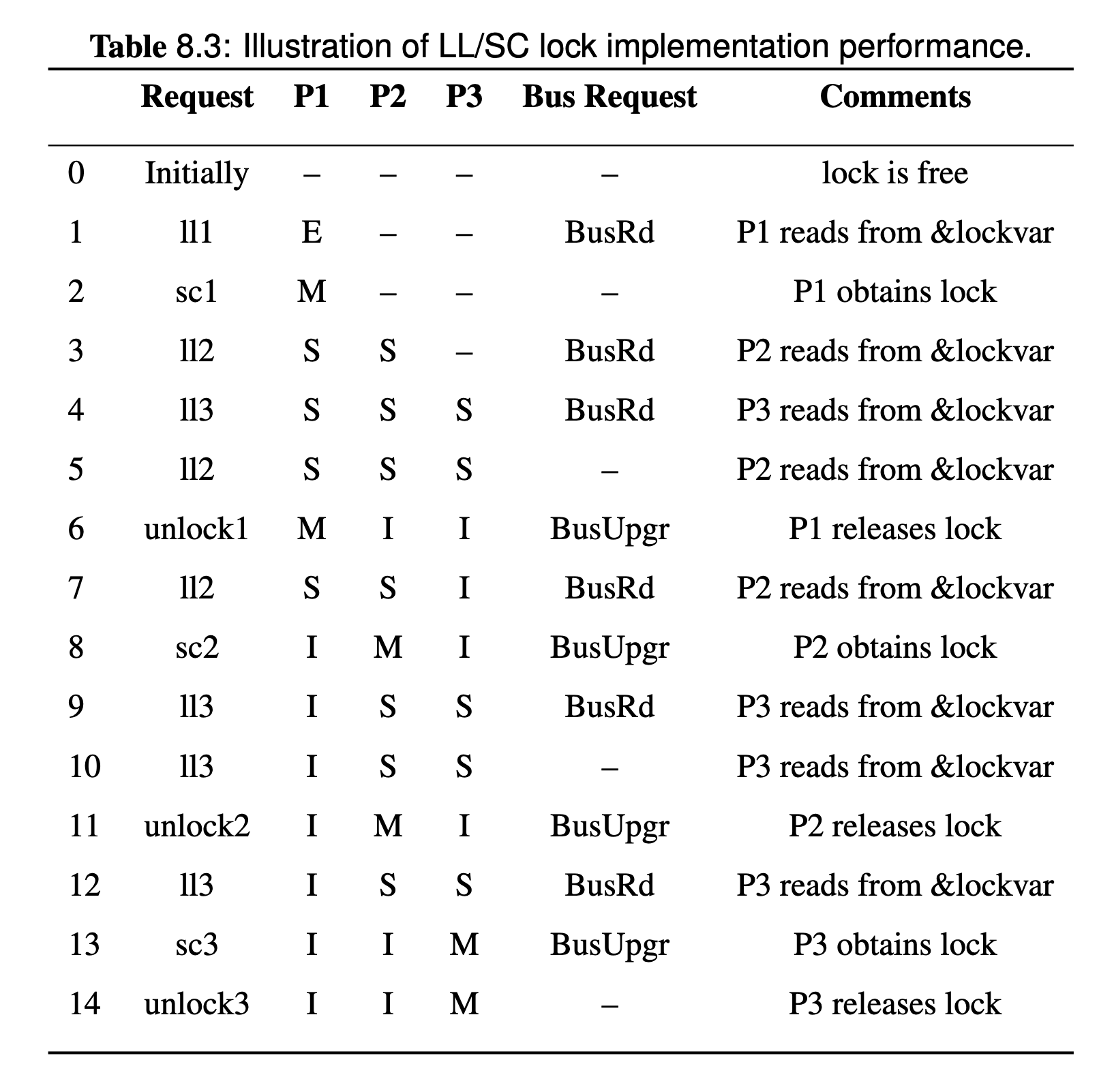

Suppose that each processor needs to get the lock exactly once. Initially, no one holds the lock. The sequence of bus transactions generated is identical to ones in the TTSL implementation, except that the LL replaces the regular load, and SC replaces the test-and-set instruction.

Performance-wise, the LL/SC lock implementation performs similarly to a TTSL. Minor difference: when multiple processors simultaneously perform SCs, only one bus transaction occurs in LL/SC (due to the successful SC), whereas in the TTSL, there will be multiple bus transactions corresponding test-and-set instruction execution. However, this is a quite rare event since there are only a few instructions between a load and a store in an atomic sequence, so the probability of multiple processors executing the same sequence at the same time is small.

LL/SC is a general and simple idea, it can be used to implement many atomic instructions, such as test-and-set, compare-and-swap, etc. Hence, it can be thought of as a lower level primitive than atomic instructions.

Lock with Fairness

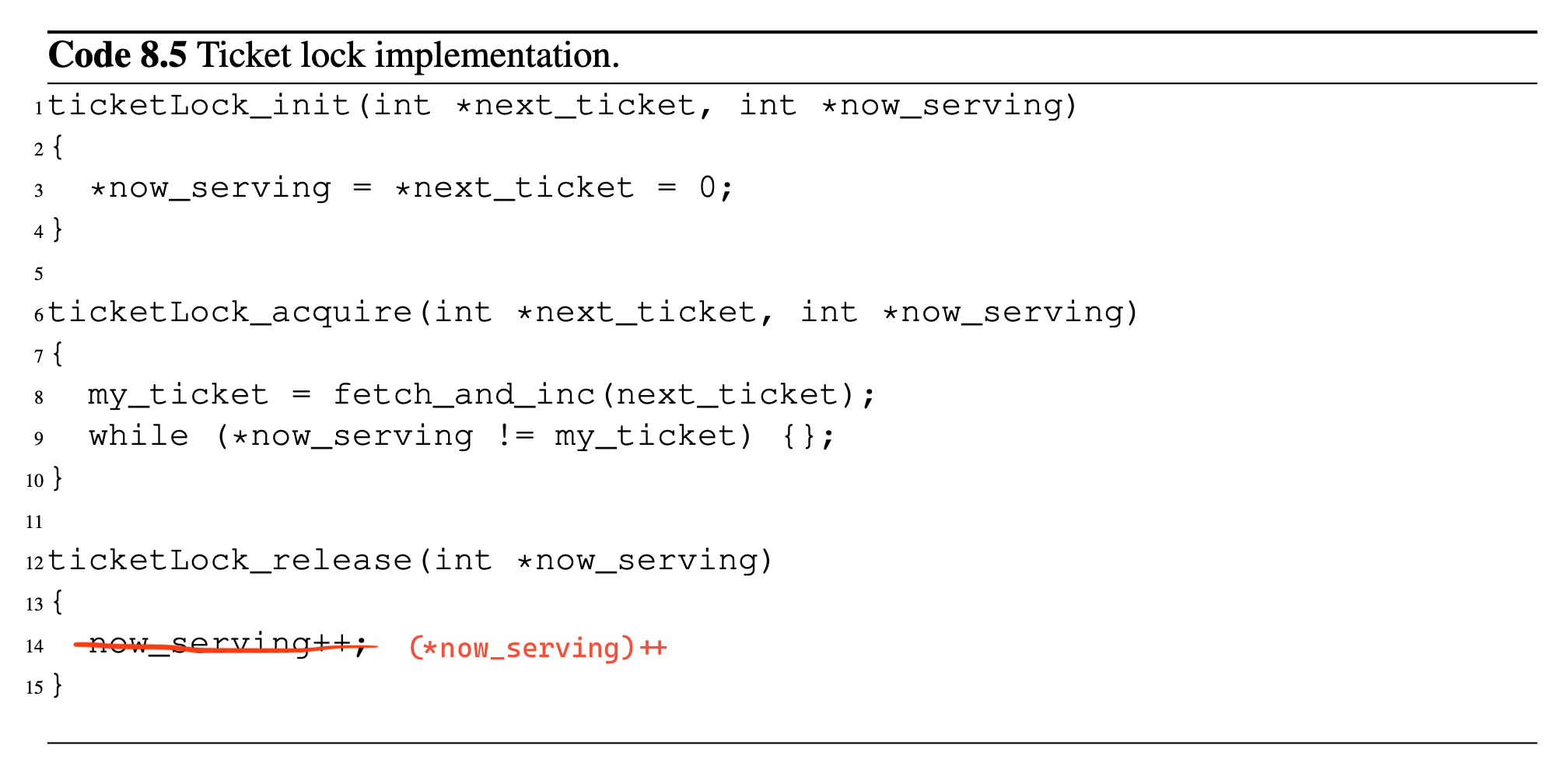

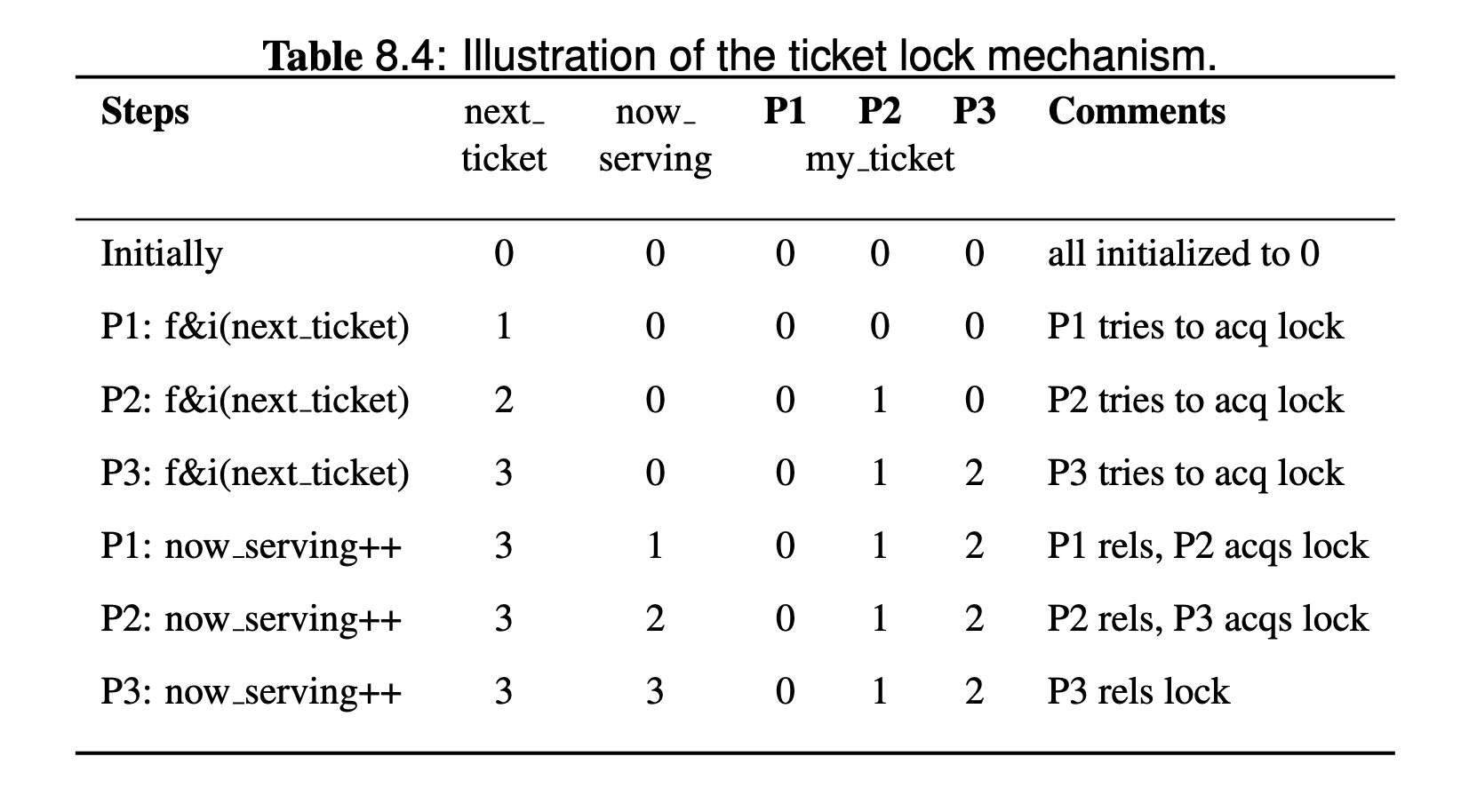

Ticket Based Lock

It's a lock implementation that attempts to provide fairness in lock acquisition using queue.

Concept: Notion of Fairness The notion of fairness deals with whether the order in which threads first attempt to acquire a lock corresponds to the order in which threads acquire the lock successfully

Each thread that attempts to acquire a lock is given a ticket number in the queue, and the order in which lock acquisition is granted is based on the ticket numbers, with a thread holding the lowest ticket number is given the lock next.

Note that the code above shows the implementation in a high-level language, assuming that there is only one lock (so a lock’s name is not shown) and fetch the atomic primitive fetch and inc() is supported. Such primitive can be implemented easily using a pair of LL and SC.

If some of the process holds the

If some of the process holds the my_ticket matches now_serving, it will enter the critical section.

Regarding the traffic, there are number of acquisition and releases, each acquisition and release cause invalidation and subsequent cache missis, the total traffic scales on the order of .

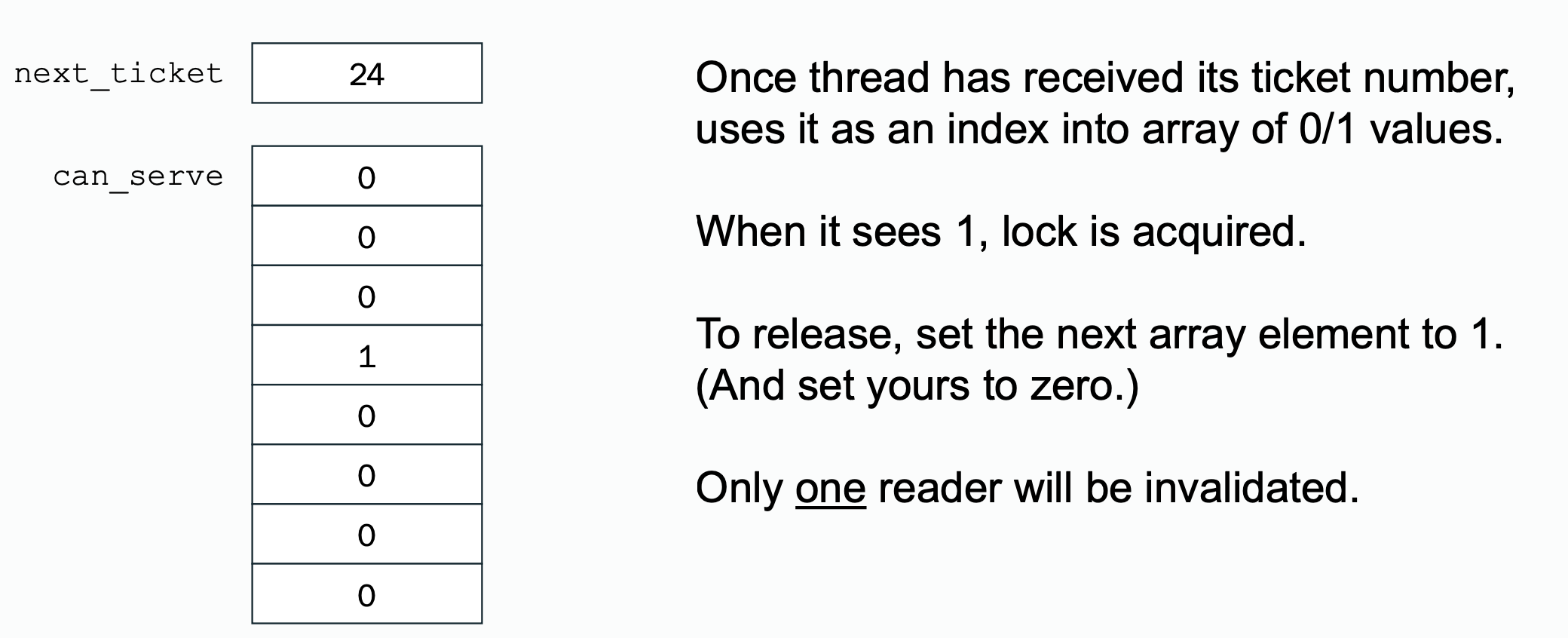

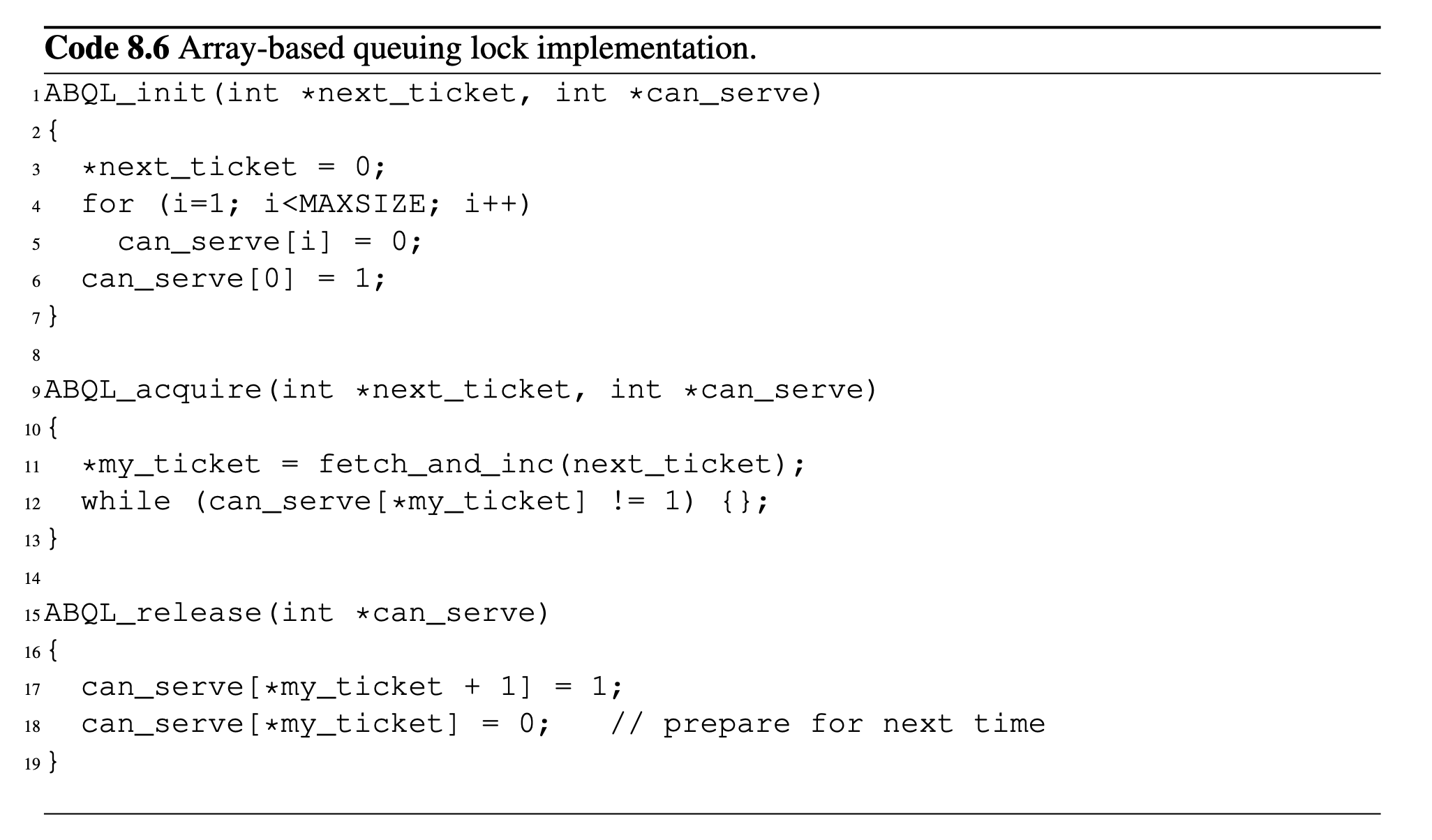

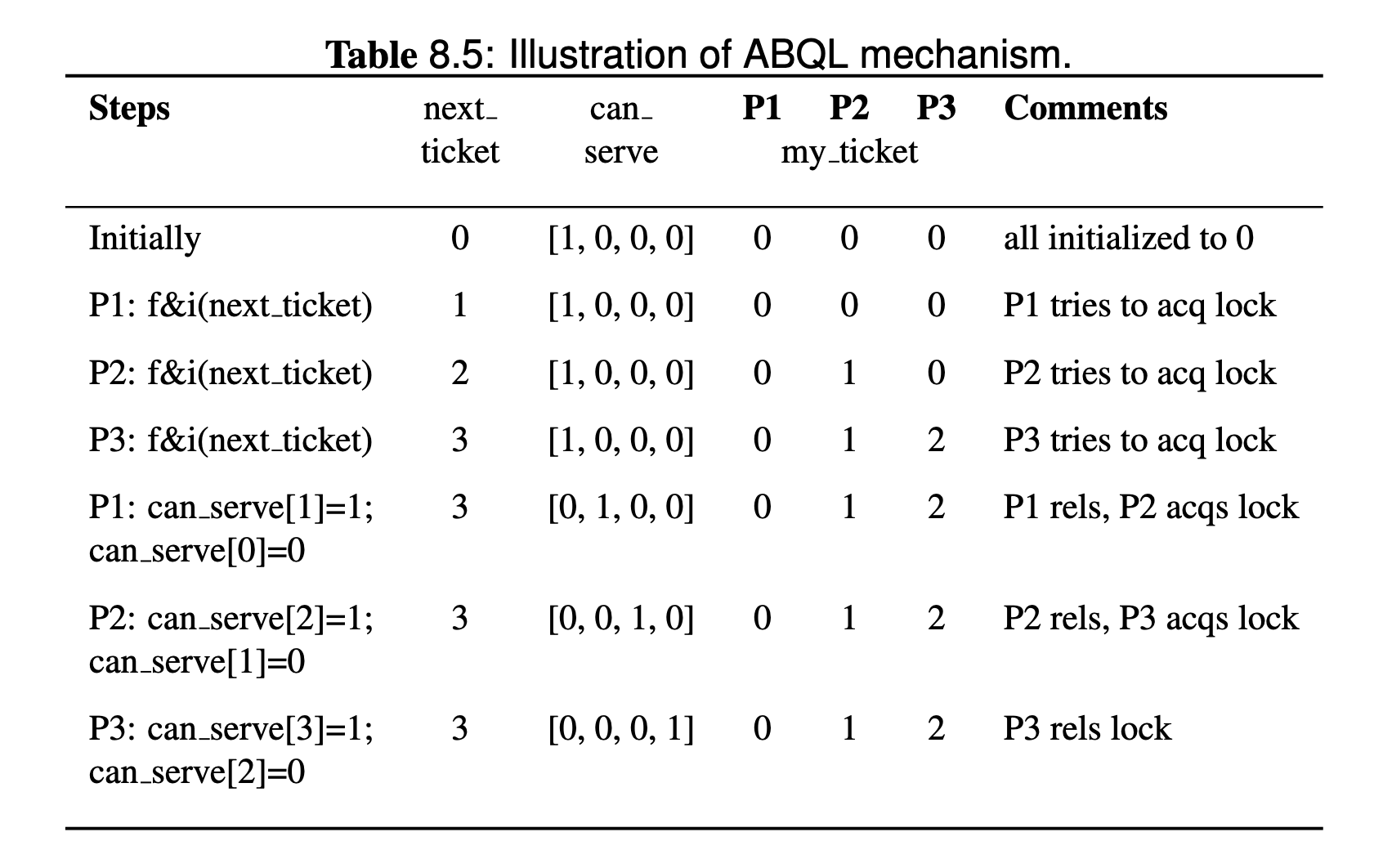

Array-based Querying Lock (ABQL)

It's some kind of improved version of ticket lock which reduces traffic to because every thread competing this lock has their own snooping location instead of a shared snooping location, which will not cause p invalidate.

The way to do it: threads can wait and spin on unique memory locations rather than on a single location represented by now serving:

Here we assume that fetch_and_inc is a atomic operation and two thread calling acquire simultaneously will not get the same ticket number.

Regarding the traffic, the write only invalidates one cache block, only traffic is generated, there are number of acquisition and releases, so the total traffic scales on the order of .

| Ticket Based | Array Based | |

|---|---|---|

| Uncontended lock acquire latency | Single atomic operation + one load. | Single atomic operation + one load. |

| Bus Traffic | Similar to TTS. Waiting = spin in local cache (read). | Lowest of the alternatives. Waiting = spin in local cache (read). Single invalidate and BusRd on release. |

| Fairness | Order of f&inc will determine order of lock acquisition. No starvation. | Order of fetch&inc will determine order of lock acquisition. No starvation. |

| Storage | Two variables - constant. | Highest - array of at least P elements. |

Barrier Implementation

Barrier implementations are not included in the final exam

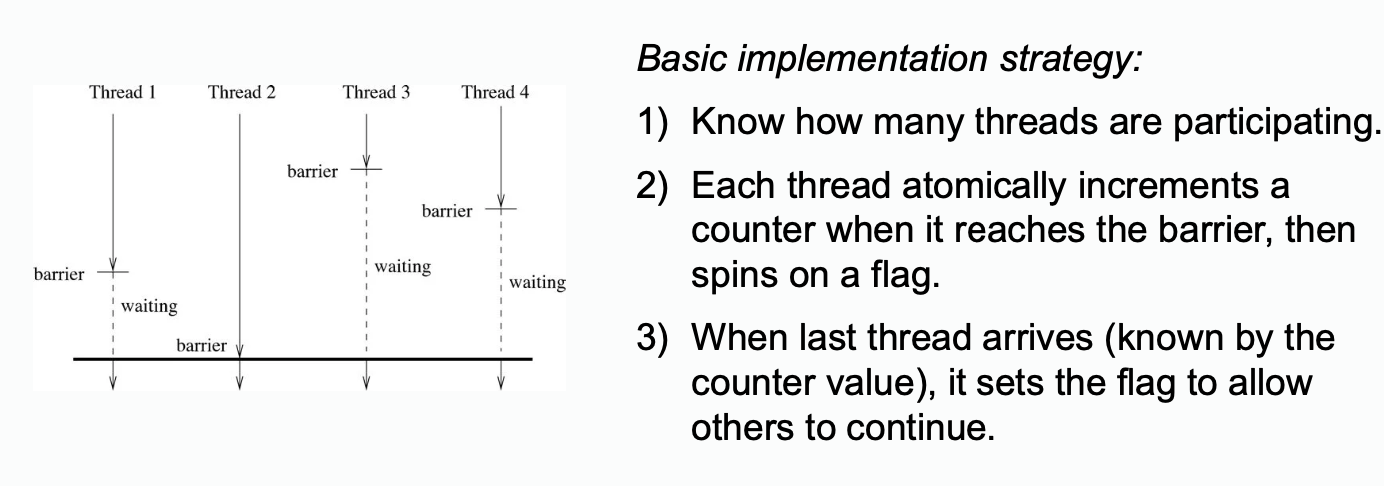

When there is a barrier, multiple threads must reach the same point before any may continue.

Summary:

- Software barrier

- Sense-reversal centralized barrier: a software barrier implementation

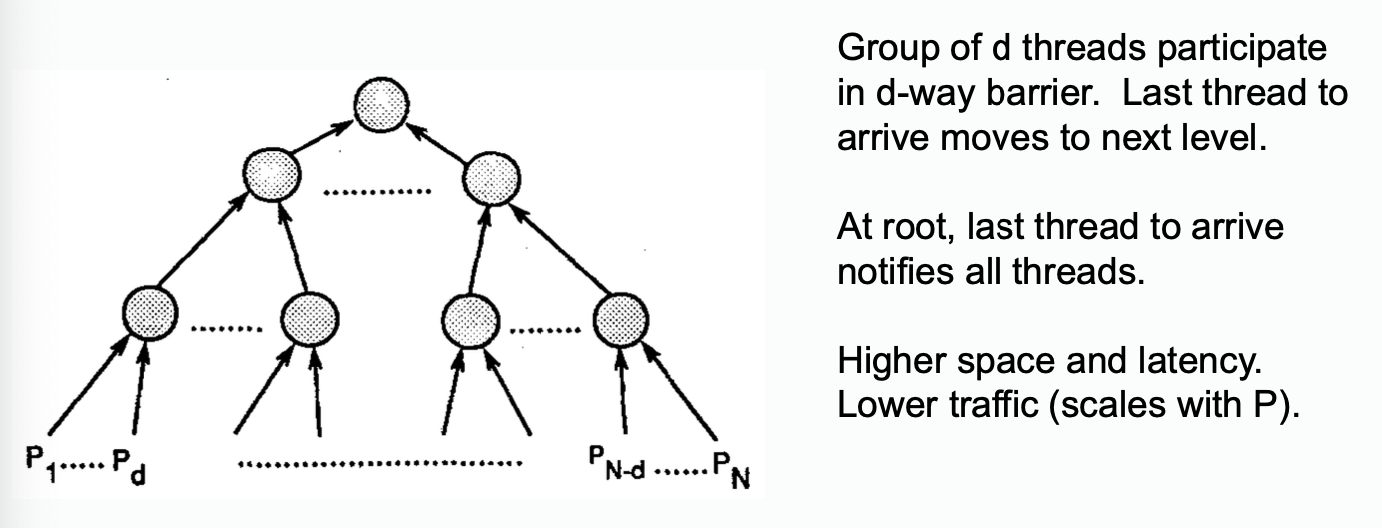

- Tree based barrier

- Butterfly Barrier

- Hardware barrier implementation

Software Barrier

Software barriers are based on locks, since there will be critical sections in obtaining the lock.

Centralized Barrier

- critical section required

Tree Based Barrier: Combining Tree

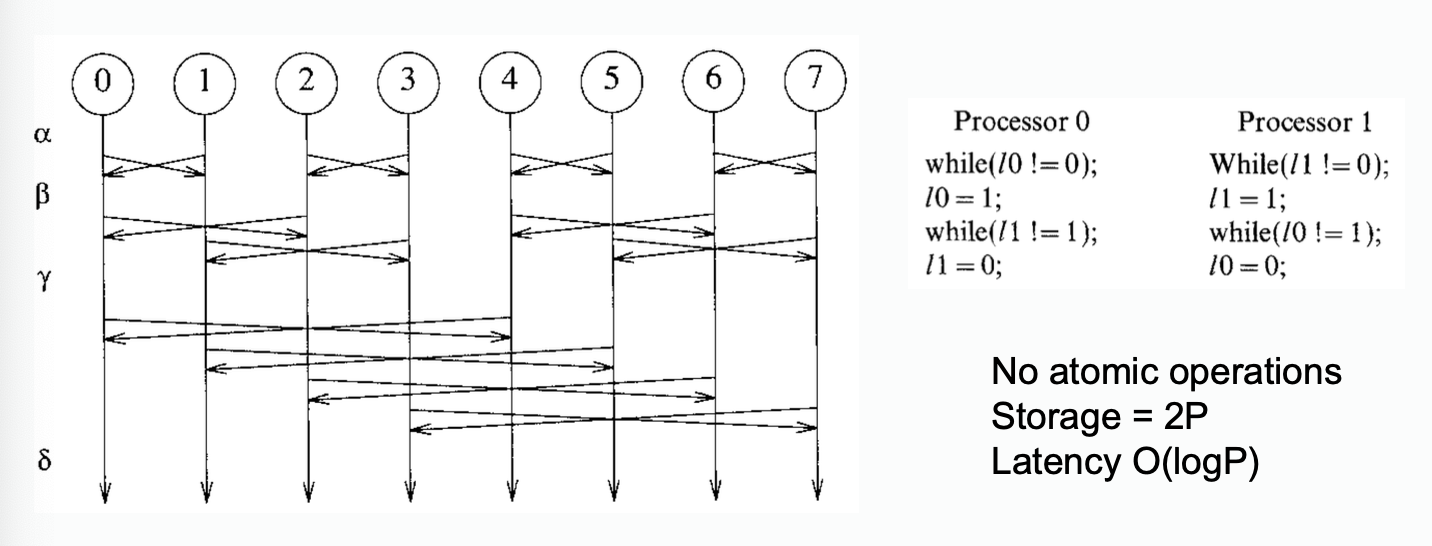

Butterfly Barrier

From a paper, E. Brooks III, Intl. J. Parallel Programming, 15(4), 1986.

- critical section not required

- needs

2*threadsstorage for synchronization variables

Hardware Barrier Implementation

- The cost is much higher than software approach.

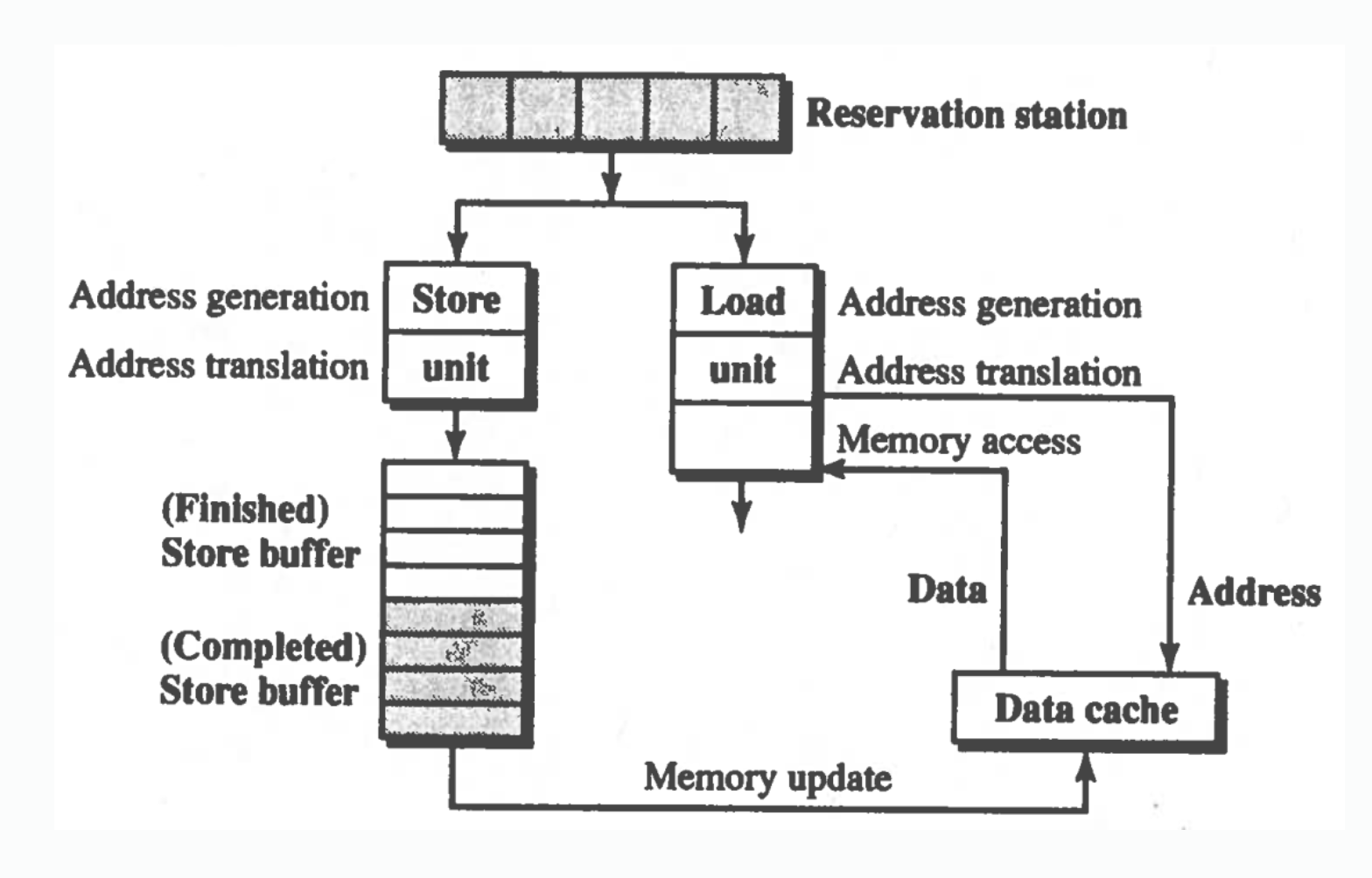

Load / Store Implementation

Load/Store implementations are not included in the final exam

Load and Store in Sequential Consistency (SC)

Load must wait for store buffer to be empty before issuing to memory.

Improving SC Performance

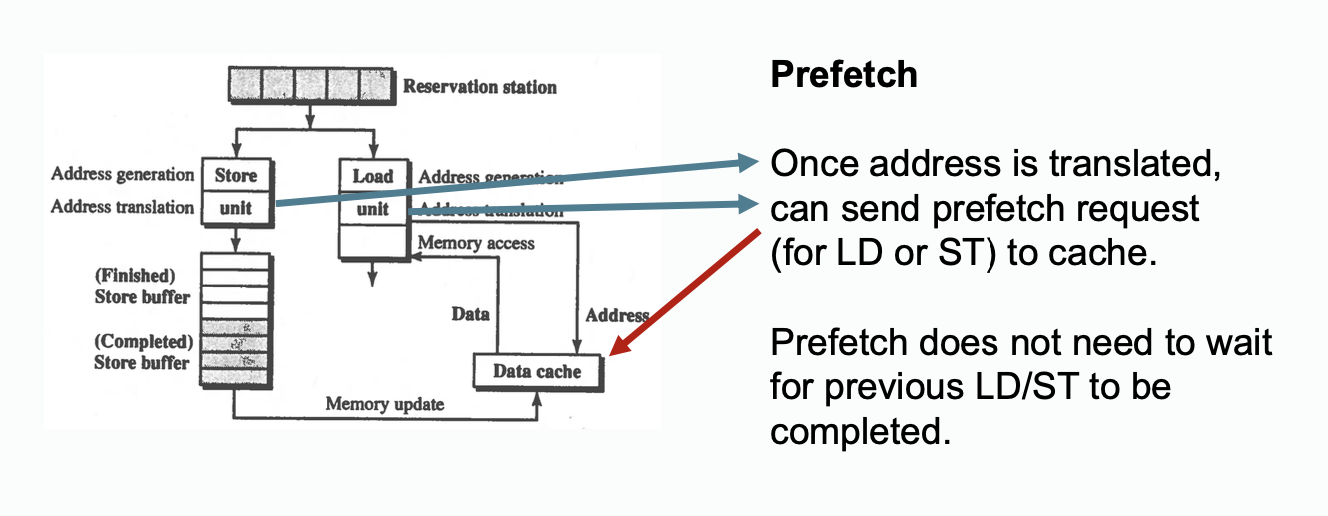

Prefetch

Recall prefetching mentioned in Lecture - Cache Coherence in Bus-based Multiprocessors.

Prefetching is not a real load, its like a hint issued to cache. Prefetching means that the processor thinks it is a good idea to fetch the address now, but its not a real load from processor, the processor may loads it later or may not. On the real load happen, the processor will still issues a load, if it is prefetched, there will be no cache miss which improves performance..

Prefetching may hurt performance, read section related to prefetching in Lecture - Cache Coherence in Bus-based Multiprocessors for more information.

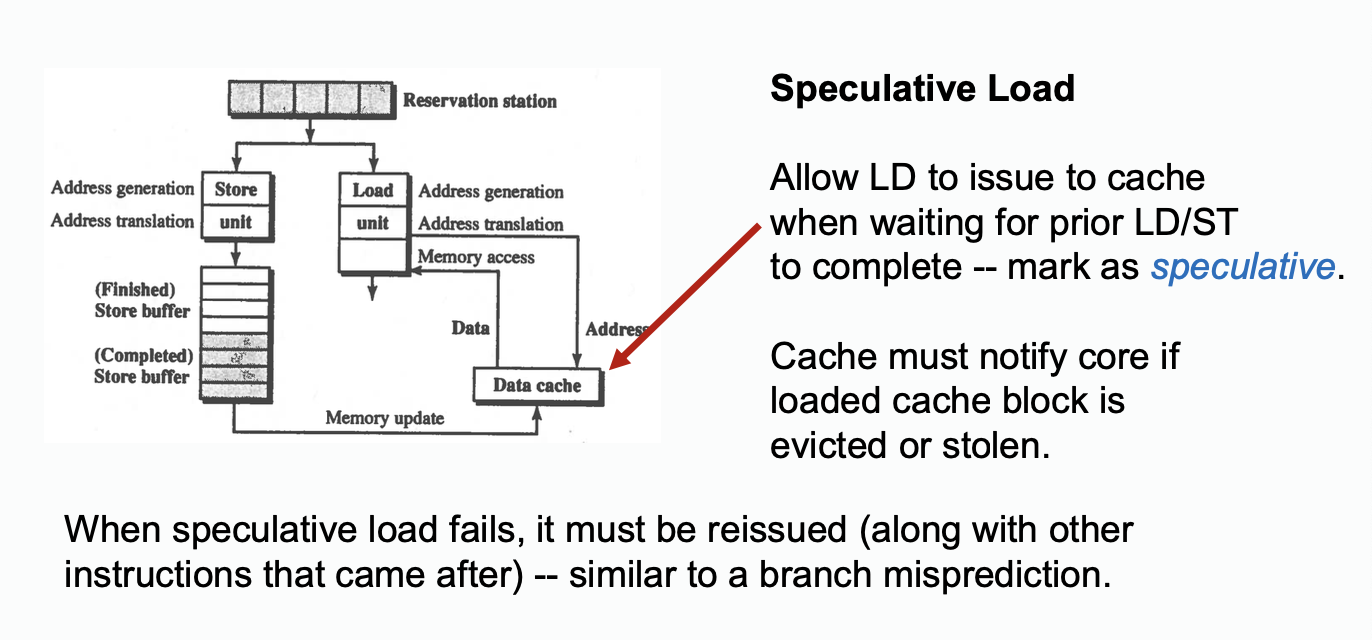

Speculated Load

The big difference between speculated load and prefetching is that prefetching is not a real load, but speculated load is a real load.

Other Memory Optimizations

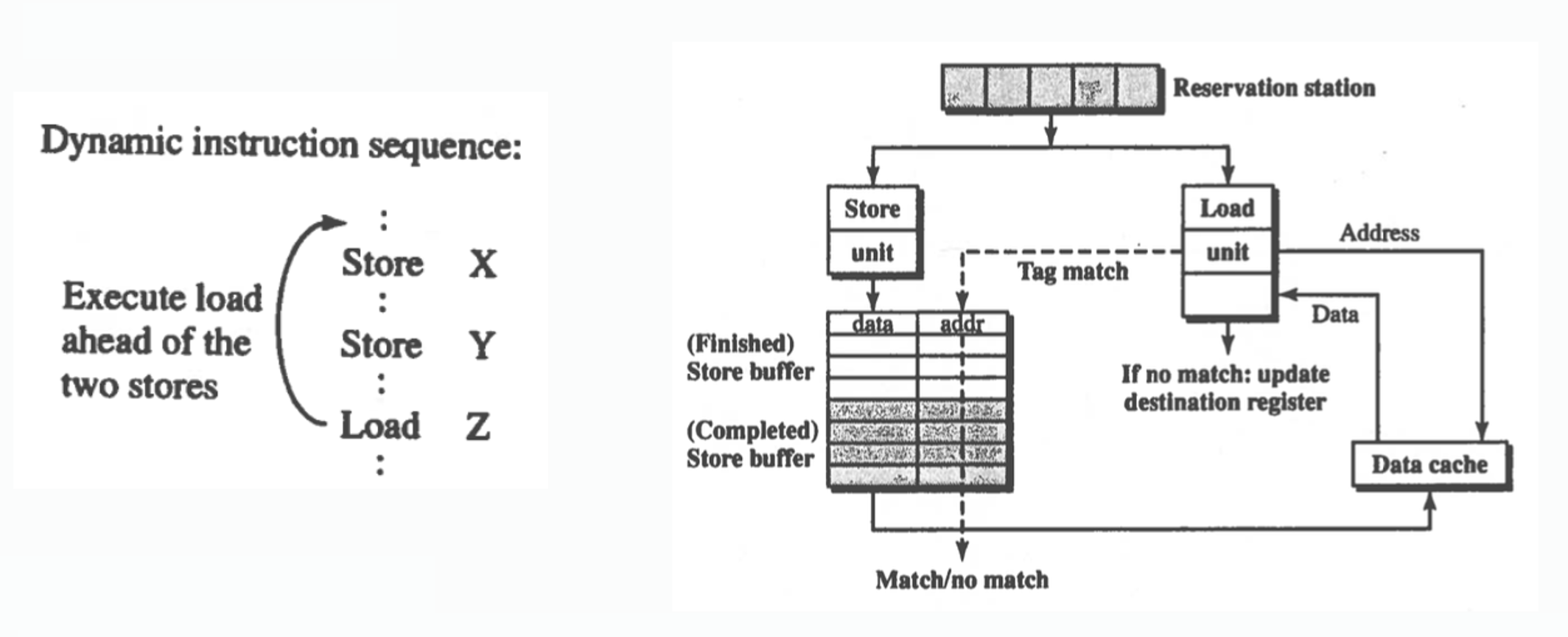

Load Bypassing

Load bypassing execute(typically in uniprocessors) load operation without waiting for store to finish when the target load and stores are on different address.

Load bypassing typically works in uniprocessor system, but when there is a multi-threading program running on multiprocessor system, the situation will not be same. For example, the following code is not allowed by SC:

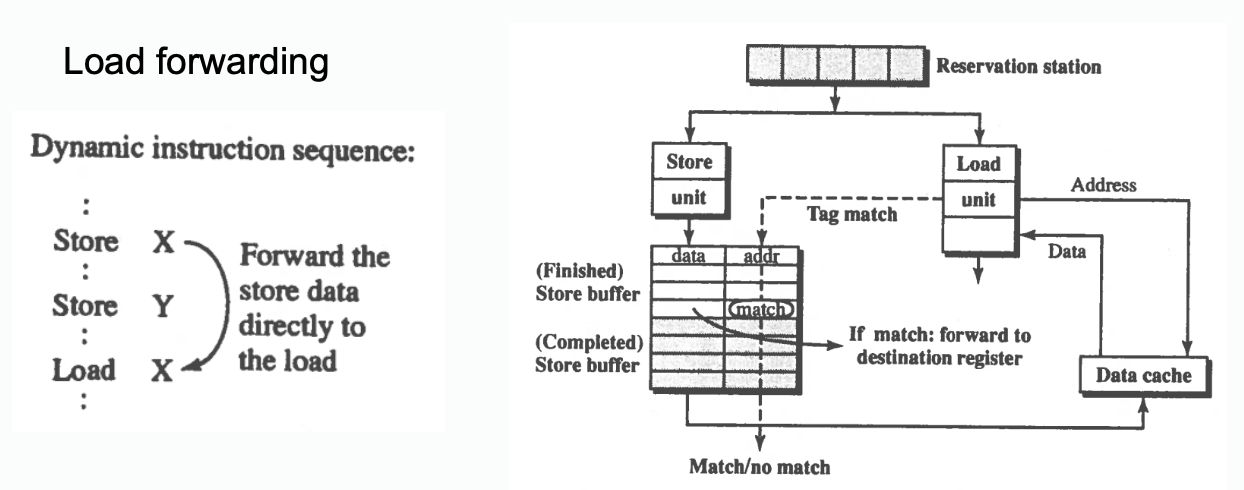

Load Forwarding

If store to X happens from another processor, loading old X will be a consistent interleaving or program order(e.g. load could have hit in cache just before intervention).