Final Exam Note

This note is written by someone(Gavin Gong, [email protected]) attending this class, not by the instructor(Dr.Greg Byrd, [email protected]) of the course(CSC506). There might be errors.

Instructor said: The exam will be closed-book and closed-notes, and no electronic devices are allowed. The material for the quiz comes from lectures and material covered in the text. In particular, all sections of the text listed in the Reading Assignments on Moodle will be the source of content for the exam.

Cache Coherence

Discuss the cache coherence problem, and the properties required to guarantee that a cache system is coherent. Define the following terms related to cache coherence: write propagation, transaction serialization.

see also Lecture - Cache Coherence

Cache coherence problem: in multiprocessor system, there is possibility of inconsistent view of memory across caches, this is caused by multiple copies of data, write back policy, and concurrent access.

Required properties to ensure cache coherence:

- Write propagation: propagates changes to other caches, and usually to the outer level of memory hierarchy.

- Transaction serialization: multiple reads or writes to the same address must be seen in the same order by all the processors

Define the following terms related to bus-based coherent caches: intervention, invalidation, upgrade, downgrade, arbitration, clean sharing, dirty sharing, snoop, snoop response.

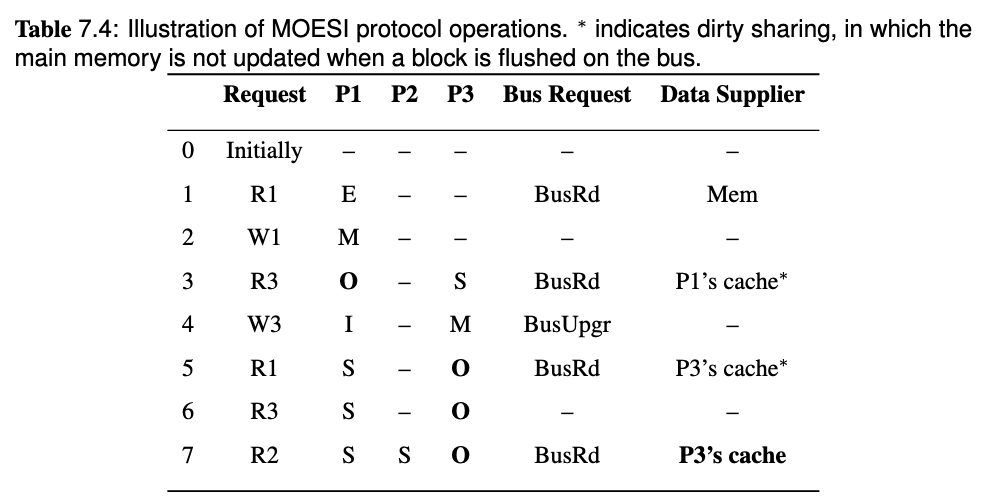

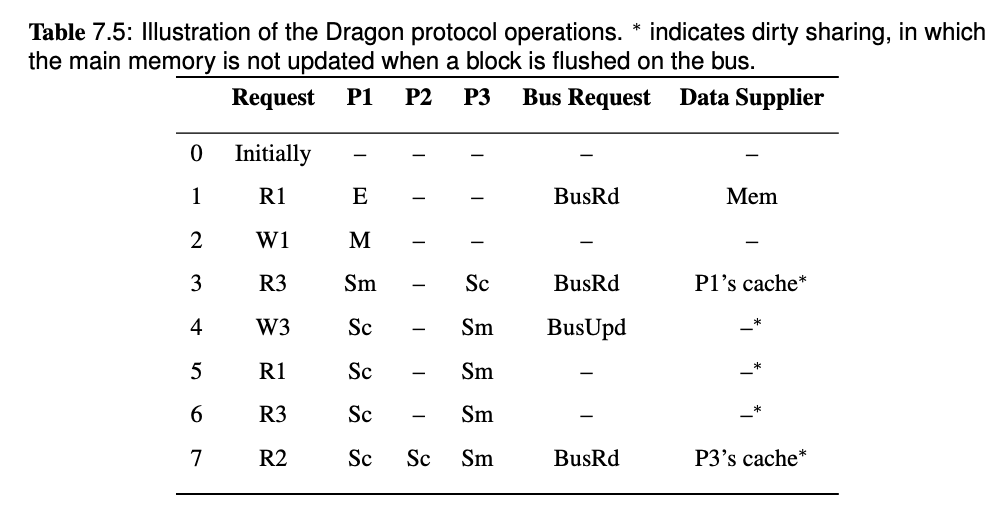

Discuss how cache coherence is maintained in a bus-based multiprocessor system using the following protocols: write-through, MSI, MESI, MOESI, Dragon. Draw the state diagram for each protocol. Given a proposed change/optimization for one of the protocols, draw the new state diagram and analyze the change in performance achieved, compared to the original protocol.

- Intervention: a downgrade which result in a final state of Shared

S. - Eviction: the act of removing a block from the cache to make room for another incoming block, this can happen due to a conflict miss or capacity miss.

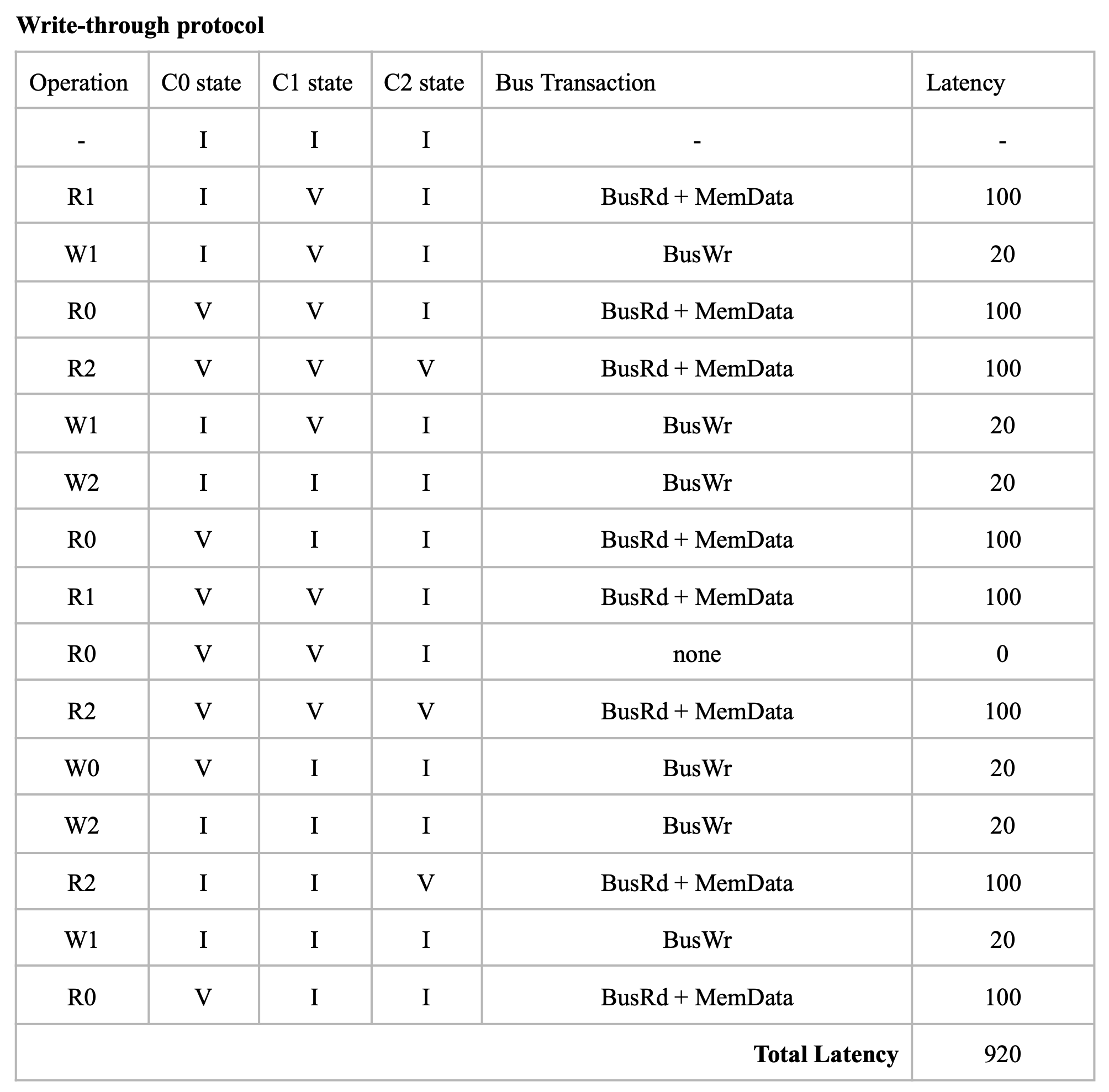

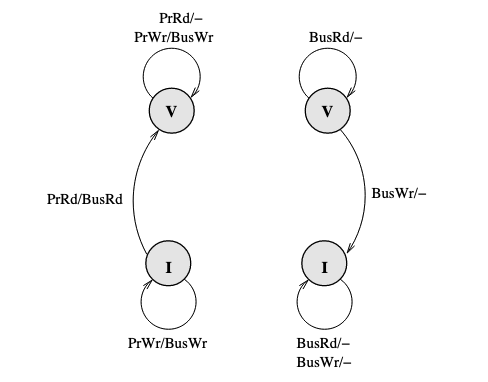

The baseline here is the basic write-through invalidate-based protocol. It uses write no allocate policy. Write through ensures that PrWr is immediately propagated out with a BusWr:

Problem here is that the write through policy cause a BusWr every PrWr(even though there might be no one who need to be notified), which consumes bandwidth.

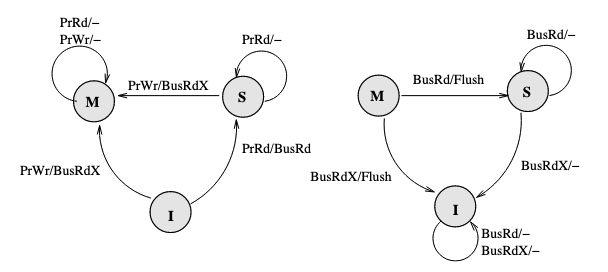

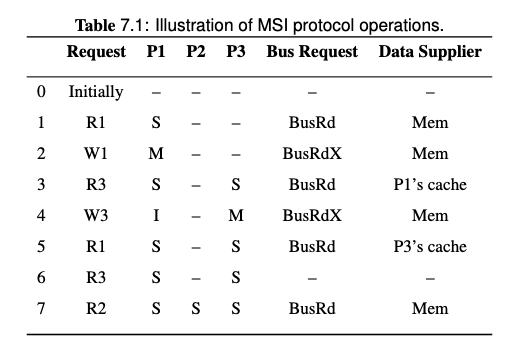

So we turn to write through policy. Write back policy introduces dirty state. The baseline here is the MSI (Modified, Shared, Invalid) protocol:

Key changes here are M(Modified) state of cache which means it is dirty, and BusRdX which notify others a block is dirty. Besides, if a BusRd is snooped on a dirty block address, a Flush will occur for write propagation. There is one thing to be improved, if the processor want to write to a address, it have to post a BusRdX, even if it already has the block.

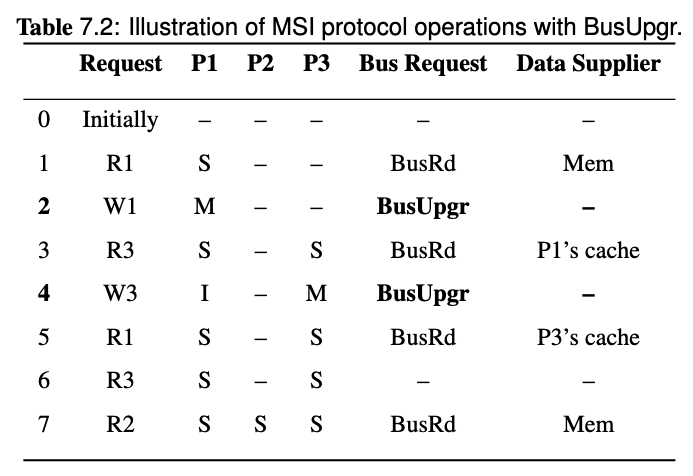

If the processor already has the block, then put the data on the bus is not necessary. Therefore, a BusUpgr is added. If the processor already has the block and want to write to it, a BusUpgr is posted instead of a BusRdX, therefore the data is not necessarily to be put on the bus which causes waste of bandwidth:

There will be no BusUpgr snooped when the cache is held in M state since there should not be other valid copies.

There is still two more things to be improved. (1) A BusUpgr has to be sent, even if there is no other copies (the reason here is that the processor does not know if there are or are not other copies). (2) Write propagation is expensive on limited memory bandwidth, but the memory will be written every time Flush happens (which can be avoided by dirty sharing).

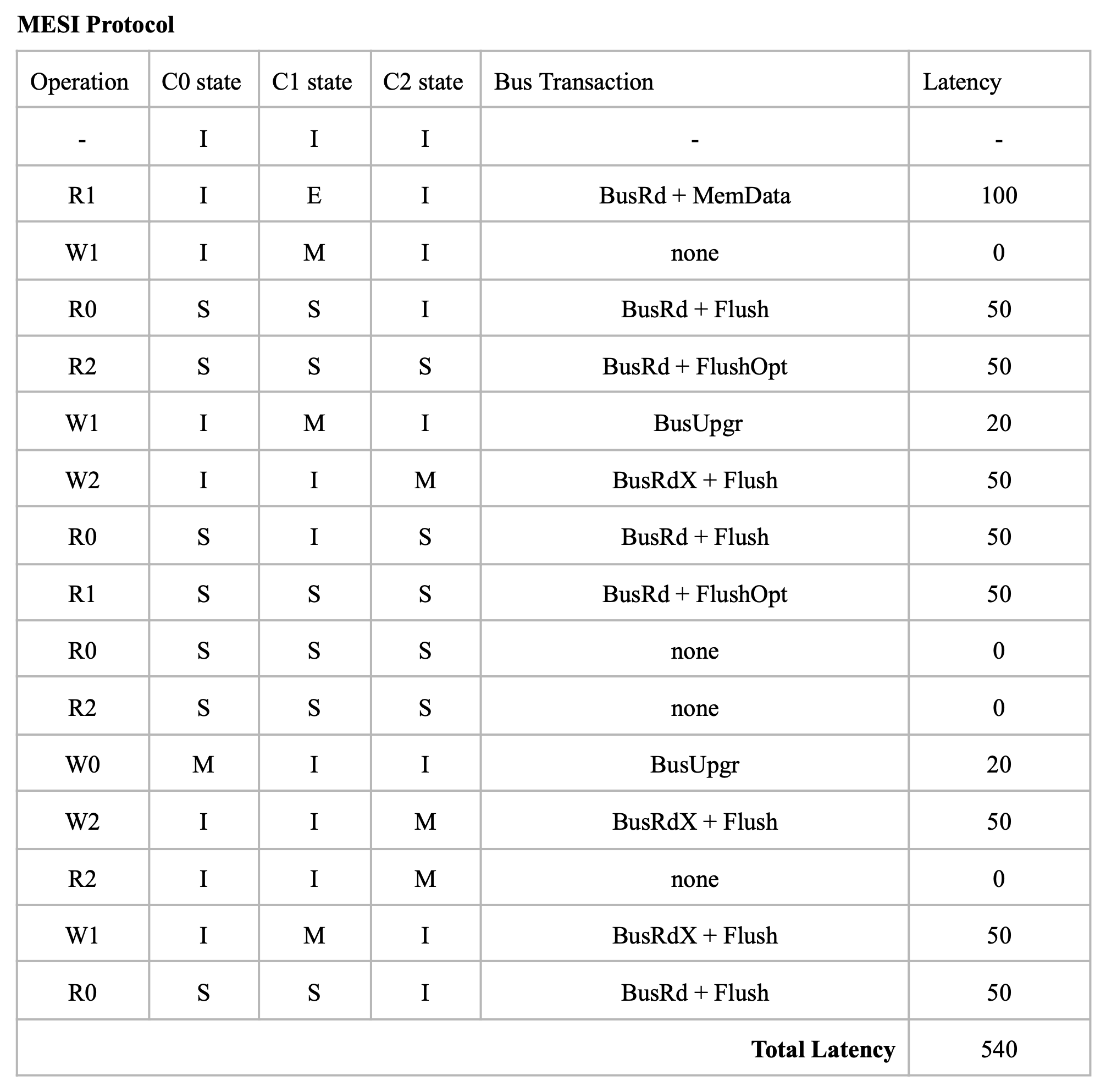

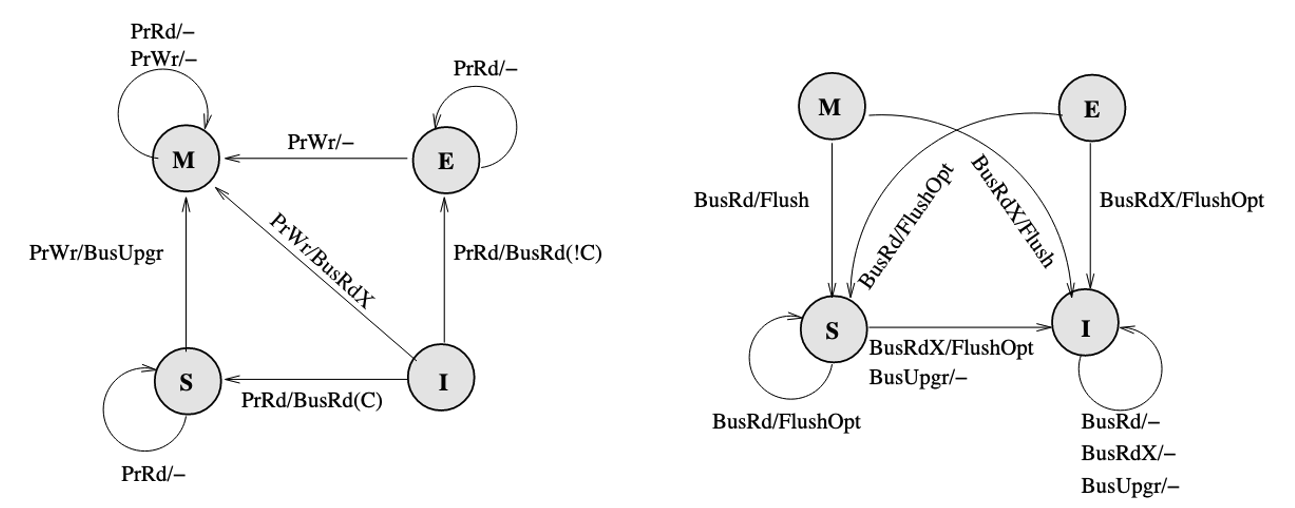

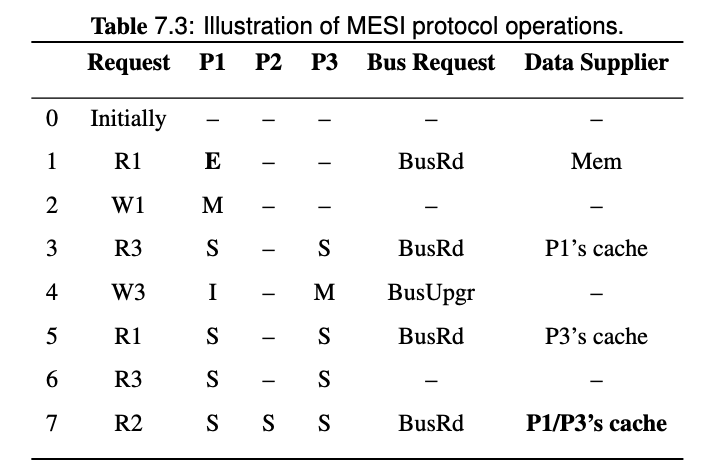

Therefore, a new protocol called MESI (Modified, Exclusive, Shared, Invalid) is proposed, which introduces a new state E (Exclusive) of cache, to represent the state that is valid, clean, and only reside in only one cache. (It can be seen as an extreme case of shared state, only one processor is sharing this with itself), it requires a dedicated bus line called COPIES-EXIST bus line (represented by C if it is asserted or !C if it is not asserted). MESI also introduces a new bus request FlushOpt, which enables dirty sharing, It does not trigger write propagation to outer memory, it means that the block is put on the bus to supply it to another processor who want it.

However, there is a problem caused by clean sharing. That is, by keep clean sharing, the main memory is updated too many times when there is a successive read and write requests from different processors to the same address.

To solve the problem, MOESI protocol is proposed which allows dirty sharing. It introduces a O(Owned) state of block, the cache who own the block will provide the block via Flush if a BusRd or BusRdX is snooped, and the main memory will not respond to Flush but only FlushWB in dirty sharing. If the block in O state is evicted, it will go back to clean sharing, the main memory will take the responsibility to provide the block, and listen to Flush but ignores FlushOpt.

The FSM of MOESI protocol:

Who will own the block? Here we assume that the last processor who writes to the address will own the block.

MSI, MESI, MOESI has made a lot of improvement compared to baseline write-through protocol. However, they are all invalidate based protocol and they suffer from a high number of coherence misses. Each read to a block that has been invalidated incurs a cache miss, and the latency to serve the miss can be quite high.

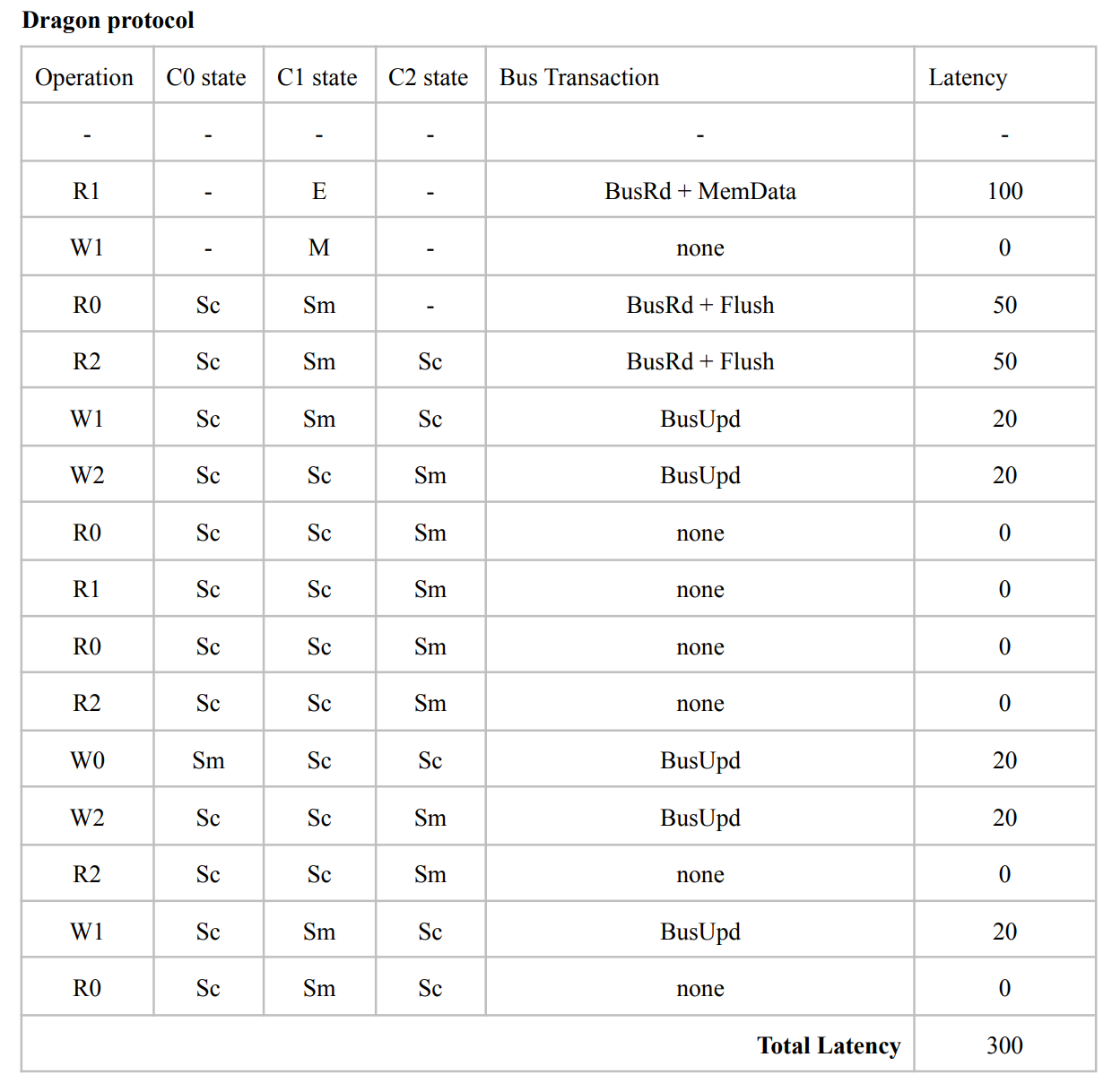

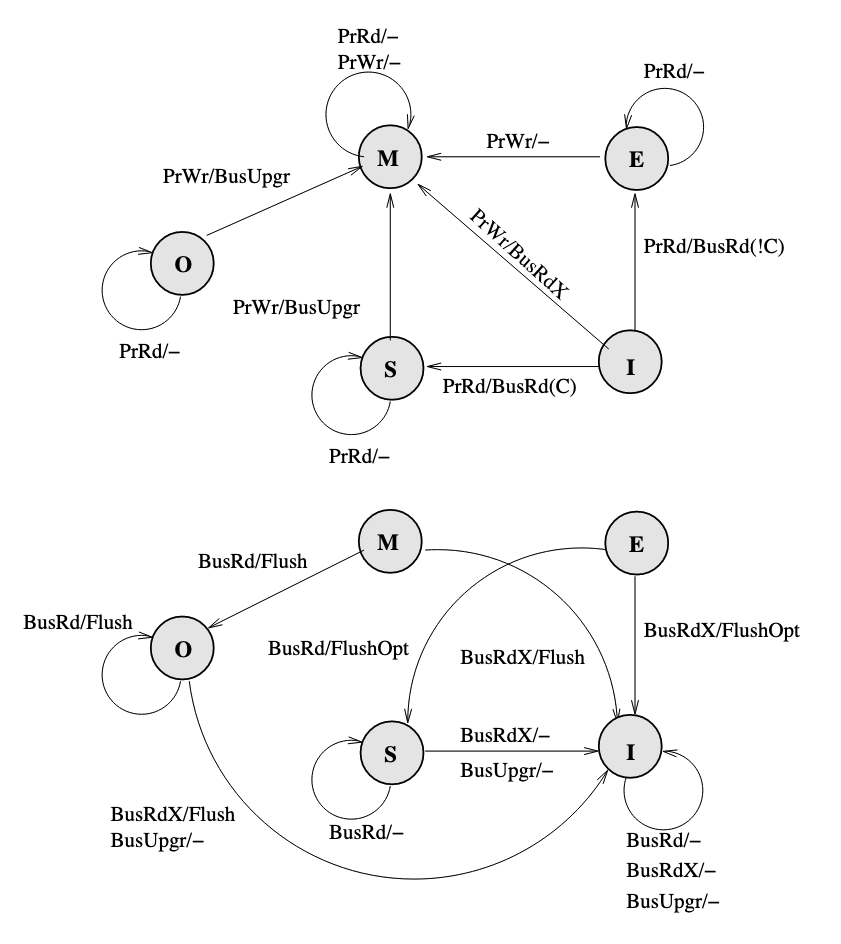

Therefore, we can overcome the overhead by removing the I state. The Dragon protocol which is a update-based protocol, does not have a I state.

For Dragon protocol, please read Lecture - Cache Coherence in Bus-based Multiprocessors, it's a little bit long to put it here.

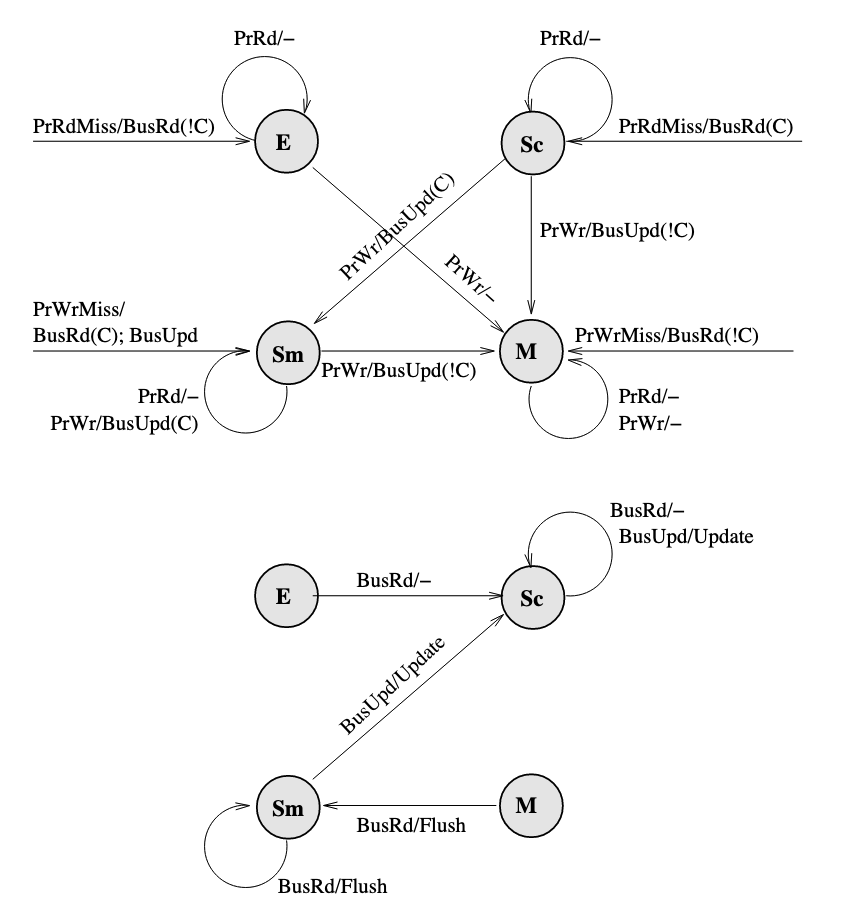

The FSM diagram of Dragon protocol:

- Note that there is no invalid state. Hence, an arrow that goes from nowhere to a state represents a newly loaded block.

- Since only

PrRdMisswill cause aBusRdbeing posted on bus, therefore the entire block is needed to be put on bus when aBusRdis snooped. - The

Mstate can only be obtained when nobody else has a copy, and the movement to this state always include a!Casserted on bus. If there are other copies, write to a block will cause the state move toSm. - A

BusUpdcannot occur when the block is inEstate because there are no other caches that have the block, and nobody else can update the block. - Only when a block is in

MorSmstate(which means it is possibly dirty), it will respond toBusRdwith aFlush. Otherwise memory should provide the block.

Given a sequence of processor requests in a multiprocessor system using one of the bus-based coherence protocols above, and a description of the memory hierarchy (cache organization, policies, latencies), show the action taken and the latency required to satisfy each request, including the state of all caches after each transaction is completed.

see also Midterm Exam Note and Lecture - Cache Coherence in Bus-based Multiprocessors, and There is another example of this question listed in Homework - 1.

Example by ChatGPT Cache Configuration:

- Cache Type: Direct-mapped cache with 8 cache lines.

- Cache Size:

- Cache Line Size: 1 word (32bit)

- Main Memory Size 64 words

- Write Policy: Write-back with write-allocate.

- Replacement Policy: Inherent in direct-mapped (no choice).

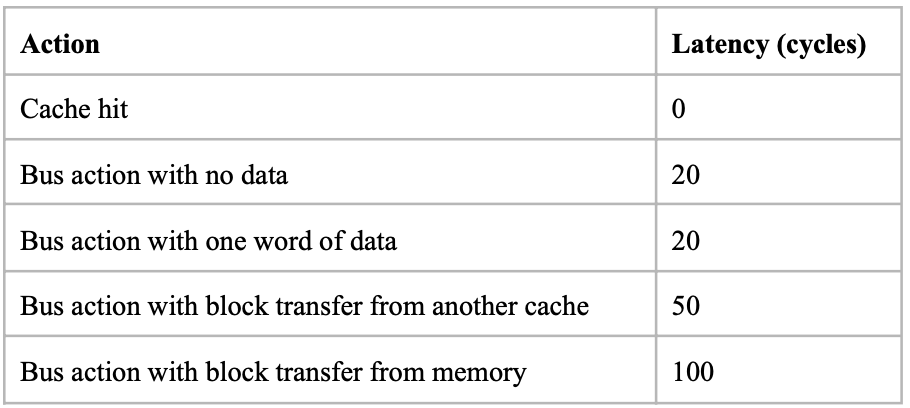

- Latencies:

- Cache hit: 1 cycle

- Cache miss (memory access): 10 cycles

- Write back memory: 10 cycles

Processor Requests Sequence:

- Read address 0

- Write address 8

- Read address 0

- Write address 0

- Read address 8

- Read address 16

- Write address 0

- Write address 16

- Read address 0

Initial Cache State: All cache lines are invalid (empty)

Actions per request:

| Request | Index (set) | Tag | Status | Action | Latency |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Read address 0 | MISS | Fetch address 0 | 10+1 | ||

| Write address 8 | MISS | Fetch address 8 Write cache address 8 | 10+1 | ||

| Read address 0 | MISS | Write back address 8 Fetch address 0 | 10+10+1 | ||

| Write address 0 | HIT | Write cache address 0 | 1 | ||

| Read address 8 | MISS | Write back address 0 Fetch address 8 | 10+10+1 | ||

| Read address 16 | MISS | Fetch address 16 | 10+1 | ||

| Write address 0 | MISS | Fetch address 0 Write cache address 0 | 10+1 | ||

| Write address 16 | MISS | Write back address 0 Fetch address 16 Write cache address 16 | 10+10+1 | ||

| Read address 0 | MISS | Write back address 16 Fetch address 0 | 10+10+1 |

Note that on step 3, the BusRd from P3 is snooped by P1, both P1 and memory will try to provide the block, but the Flush from P1 is snooped by memory so the memory will cancel the fetch attempt. Memory will also pick the Flush request and update the memory.

Therefore, the data supplier of step 3 is P1's cache.

Note that since we introduced cache-to-cache transfer and FlushOpt in MESI protocol, all the share holders of the block will try to supply the block, and one of them wins and supplies the block eventually. Since it's hard to know who will win, then the data supplier is P1/P3's cache in the last request of this example.

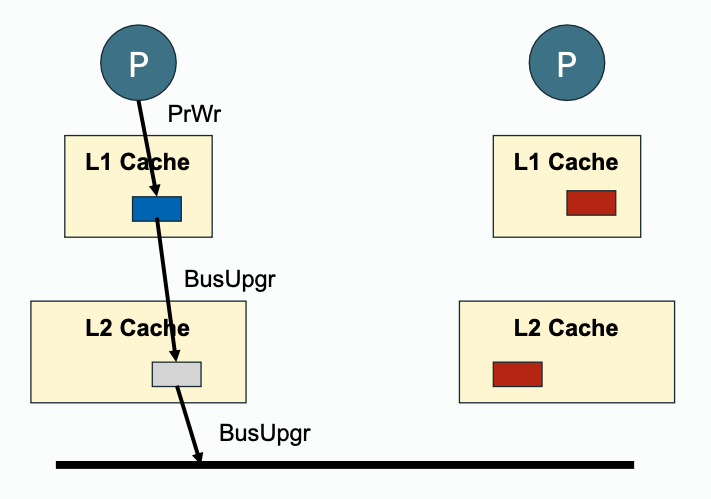

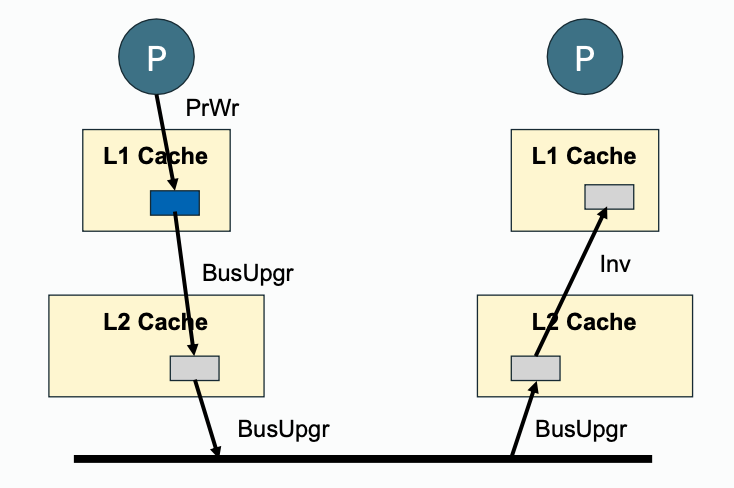

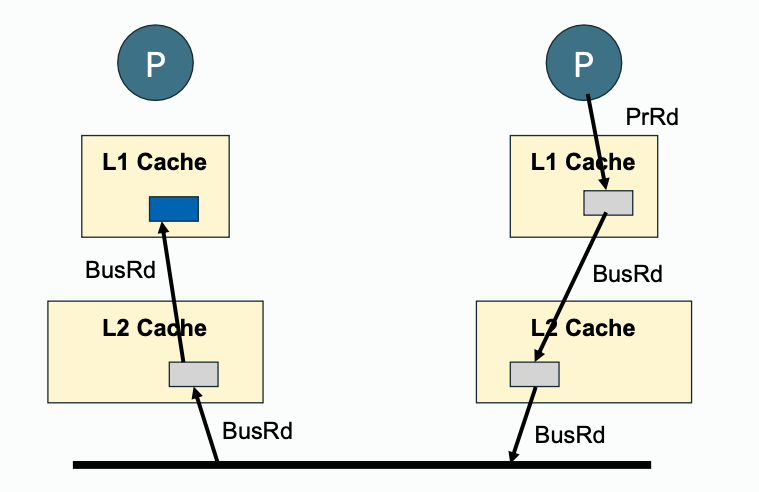

Discuss how multi-level caches maintain coherence in a bus-based multiprocessor.

This is also mentioned in Midterm Exam Note, see also Lecture - Cache Coherence in Bus-based Multiprocessors

Write propagation must be performed downstream (towards outer memory, going out of private cache) and also upstream (snooped cache state change, update with inner cache).

| Downstream | Upstream | |

|---|---|---|

| Write Propagation |  |  |

| Read Propagation |  |  |

With different inclusion policy,

- For exclusive, outer level of memory hierarchy does not hold the block, every time it must check with the inner level wether or not the inner level cache holds the block.

- For inclusive, outer level of memory hierarchy has the same blocks, so it can check itself when snooping some requests.

Discuss how snoopy coherence protocols can be implemented in systems that do not use a centralized bus interconnect. (Specific consideration for ring-based interconnection topologies will not be included on this exam.) Reason about how the requirements for cache coherence can be satisfied. Given a proposed coherence protocol (high-level, not specific state diagrams), explain how the proposal does or does not achieve coherence.

This is also mentioned in Midterm Exam Note, see also Lecture - Cache Coherence in Bus-based Multiprocessors

To maintain transaction serialization and write propagation:

- Interconnect are used to propagate data from one processor to another.

- A sequencer is responsible for managing the service ordering of upcoming requests.

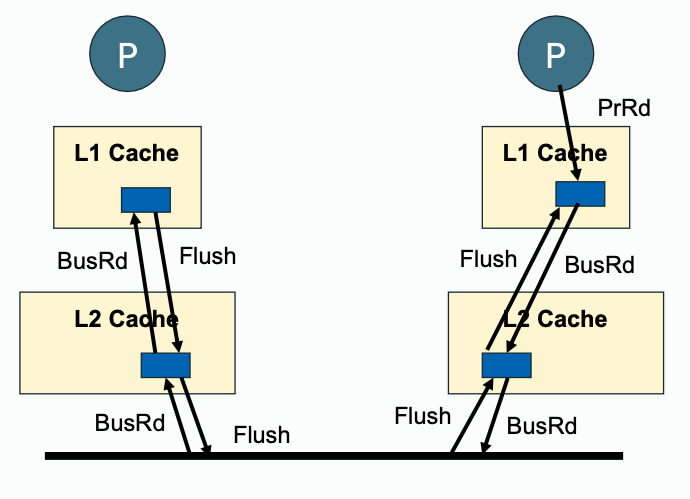

Example: 6-node system P2P interconnected, simultaneous write

Assume each node to have a processor/core and a cache. Now suppose that node A and B simultaneously want to write to a block that they already cached in a clean state. Suppose that node S is assigned the role of sequencing requests for the block.

Suppose that the request from node A arrives at node S before the request from node B. Here is what happens:

- (b) A and B sent

Upgrto S. - (c) S needs to ensure that the write by A is seen by all cores as happening before the write by B. To achieve that, S serves the request from A, but replies to B with a negative acknowledgment (

Nack) so B can retry its request at a later time. - (c) To process the write request from A, S can broadcast an invalidation (

Inv) message to all nodes as shown in part. - (d) All nodes receive the invalidation message, invalidate the copy of the block if the block is found in the local cache, and send invalidation acknowledgment (

InvAck) to node A. - (e) After receiving all invalidation acknowledgement messages, A knows it is safe to transition the block state to modifed, and to write to the block. It then sends a notice of completion to the sequencer S

- (f) Upon S receiving the notice from A, the sequencer knows the write by A is completed, it then proceed next to the request from B.

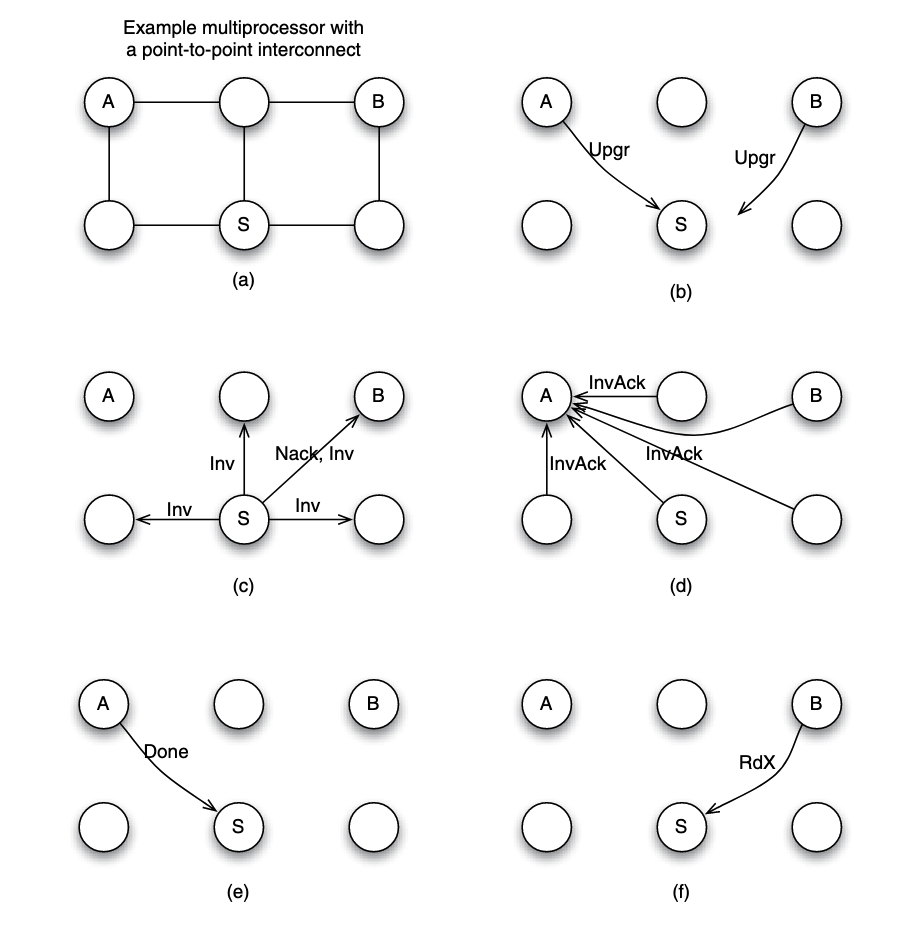

Example: 6-node system P2P interconnected, simultaneous read

Suppose that node A and B simultaneously want to read to a block that they do not fnd in their local caches. This situation is unique since it does not involve a write request, therefore we are not dealing with two different versions (or values) for the data block. Thus, it is possible to overlap the processing of the two requests.

- (a) Both node A and B send the read request to node S. Suppose that request from node A arrives earlier in node S, and hence it is served first by S. The sequencer S can mark the block to indicate that the read has not completed.

- (b) S does not know if the block is currently cached or not, or which cache may have the block. So it has to send an intervention message to all nodes (except the requester A), inquiring if any of them has the data block.

- (c) Suppose that node C has the block and supplies the block to A, while other nodes reply with NoData message to A.

- (d) In the mean time, let us suppose that the sequencer receives a new read request by node B. Since this is a read request, the sequencer can overlap the processing safely, without waiting for the completion of the outstanding transaction. It sends intervention message to all nodes except the requester B.

- (e) Nodes A and C have a copy of the block, and hence both may send the data block to node B.

Discuss the principles of a directory-based cache coherence protocol, including its difference from snoop-based protocols. Describe the fundamental operations required to enforce coherence in a directory-based scheme.

Discuss how cache coherence is maintained in a directory-based multiprocessor system using the following protocols: MESI, MOESI. Draw the directory's state diagram for each protocol. (NOTE: The MOESI option is not discussed in the text, but it is a natural extension of MESI.)

Difference: Directory coherence protocol avoids large broadcasting traffic in broadcast/snoopy protocols. In a directory approach, the information about which caches have a copy of a block is maintained in a structure called the directory.

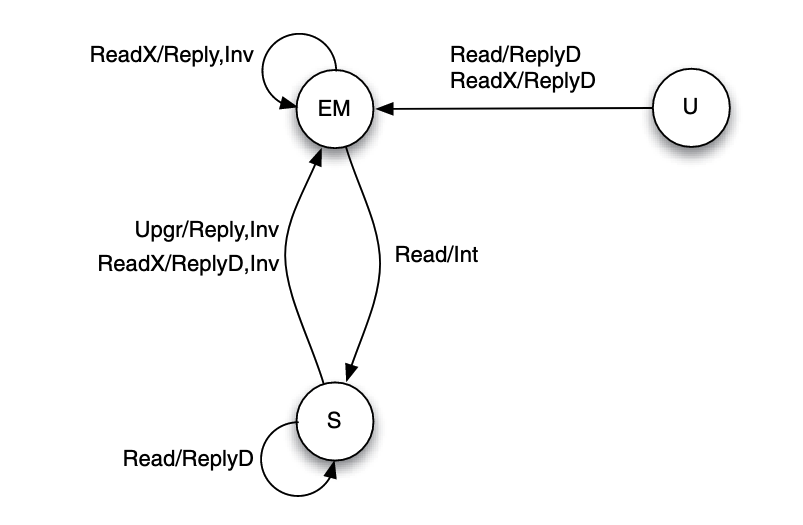

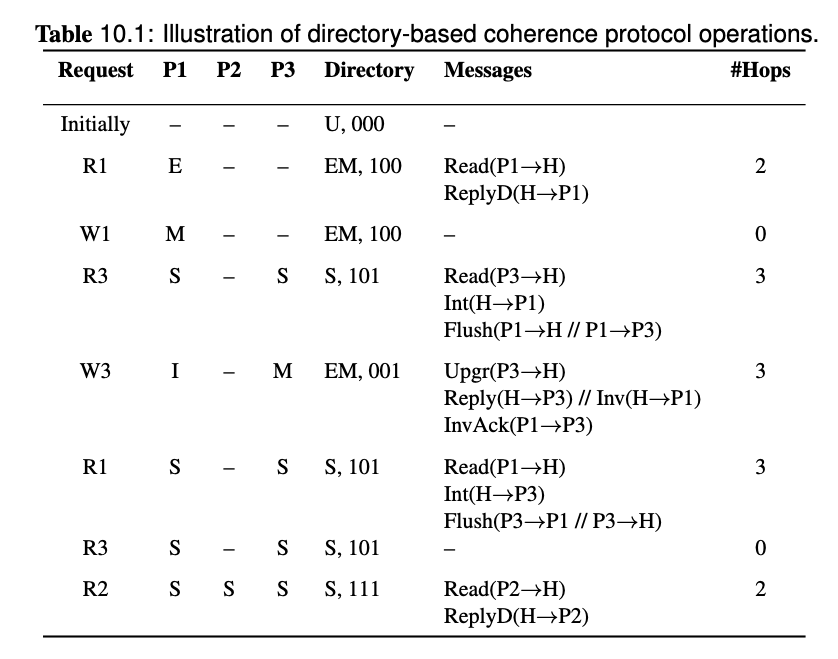

Assuming basic MESI protocol, the cache will be using the MESI state diagram, and the following diagram is the directory's diagram:

Block state change from exclusive to modified silently, this is not distinguishable by the directory, therefore it is marked in the same stat EM.

The directory's states reflects all the share holders of memory locations. If the memory location is marked as U in directory, it means there is no holder of this memory location.

When transfer from EM to S state, the directory will not send ReplyD, it will sent Int to modified/exclusive holders so that they can send the data themselves.

New states introduced (compared to MESI):

- Uncached (U): has not been loaded or has been invalidated.

New bus request introduced (compared to MESI):

- ReplyD: reply from the home to the requester containing the data value of a memory block.

- Reply: reply from the home to the requester not containing the data value of a memory block.

- Inv: an invalidation request sent by the home node to caches.

- Int: an intervention (downgrade to state shared) request sent by the home node to caches.

- InvAck: acknowledgment of the receipt of an invalidation request.

- Ack: acknowledgment of the receipt of non-invalidation messages.

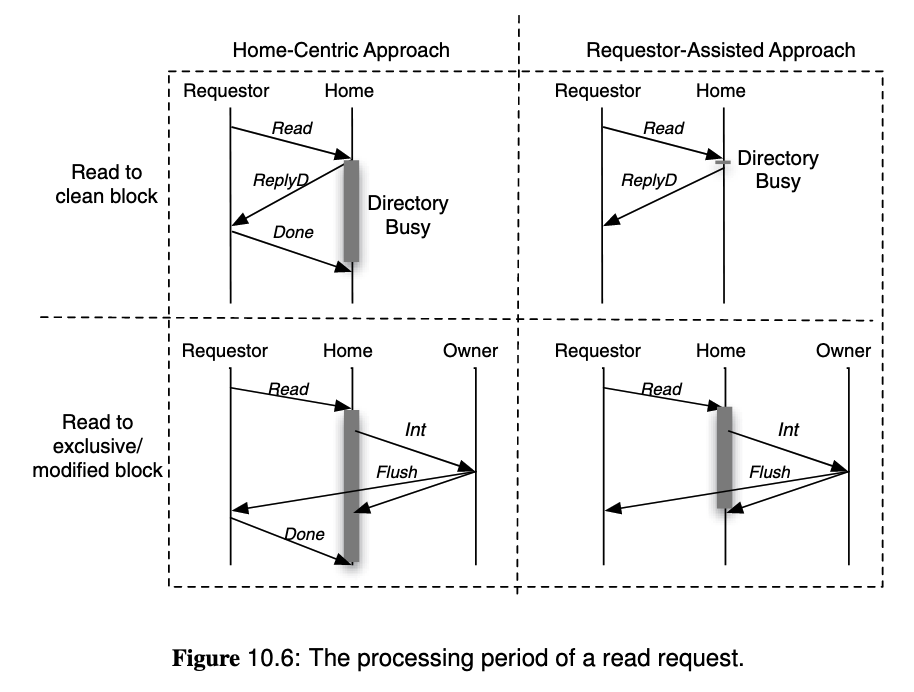

On cache read miss:

The requester will send a Read(for PrRd) to directory. Then the directory checks the block's status

- if the block is in uncached

Ustate, it fetches the block from memory and sends a reply with dataReplyDto the requester, and it transactions toEMstate. - if the block is in Shared

Sstate, it sends a copy of the block withReplyDand update the record to indicate that the requester has the block too. - If the block is in modified

Mstate, the directory instructs the owning cache to write back the block to memory by sending a intervention requestIntto it, and the intervention request also contains the ID of the requester so that the owner knows where to send the block, so it sends aReplyDto the requester.

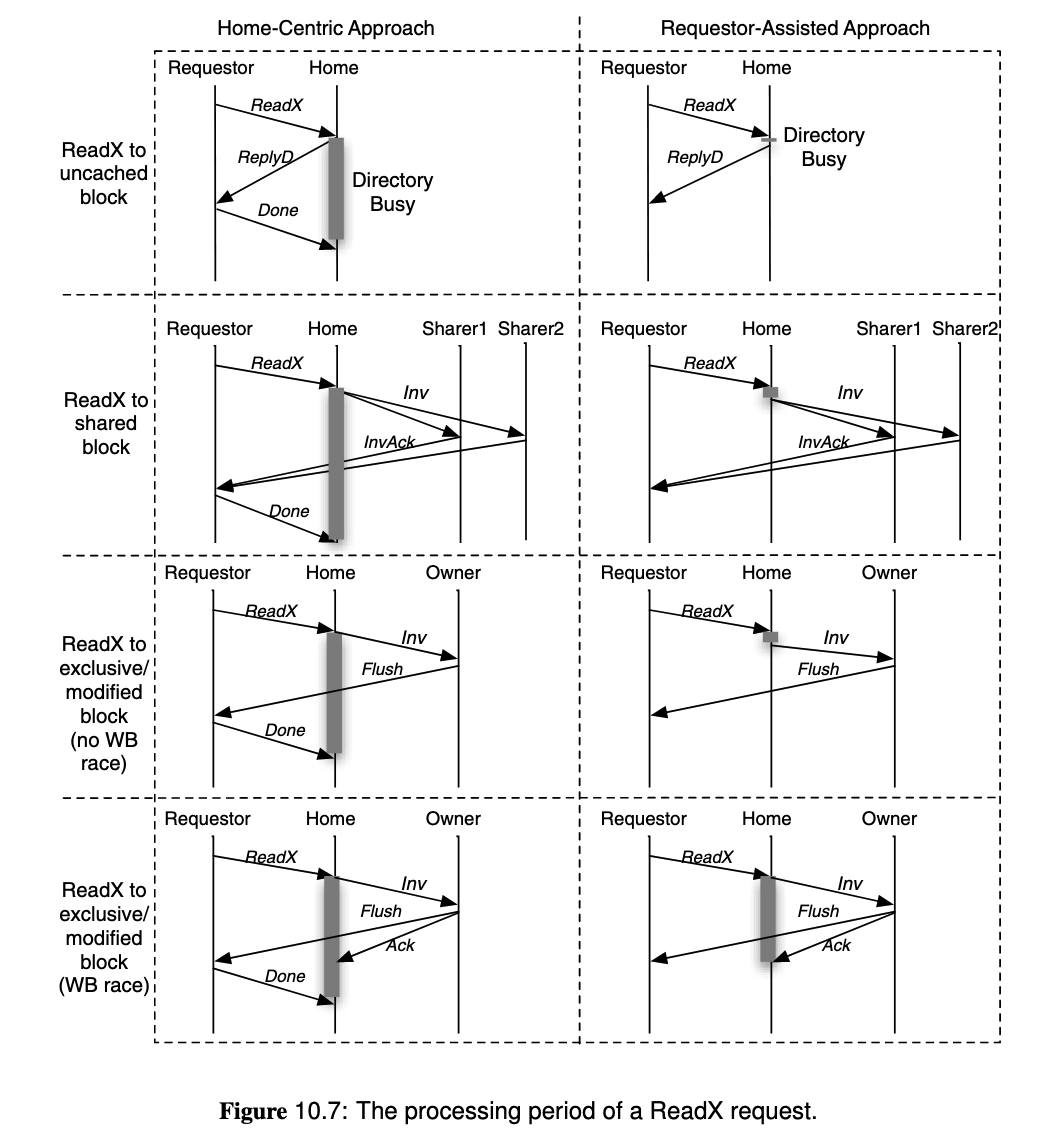

On cache write miss:

The requester will send a ReadX(for PrWr) to directory. Then the directory checks the block's status:

- if the block is in shared

Sstate, the directory sends invalidation requestInvto shared holders, and update the record to indicate that the requester has the block inMstate. - if the block in modified

Mstate, the directory also send invalidation, but the target cache will do a write-back if applicable, or forward it to the requester, then all other copies will be invalidated.

- Write propagation is achieved by sending all requests to directory, which will then send invalidations to all sharers. On a miss, the directory provides the most recently written data by either:

- retrieving from memory

- or sending an intervention to the cache that owns a dirty block.

- Transaction serialization is achieved by making sure that all requests appear to complete in the order in which they are received (and accepted) by the directory. Stalling can be done by NACK or by buffering requests.

Correctness is promised by the assumption that

- the directory state and its sharing vector reflects the most up to date state in which the block is cached

- messages due to a request are processed atomically (without being overlapped with one another)

Describe different approaches to maintaining sharing state in a directory, including full bit-vector, coarse vector, limited pointer, and sparse directory. For each scheme, describe how sharing information is updated in reaction to cache activity. Given a description of a different scheme (not in this list), show how sharing information is updated.

see also "Storage Overheads" part in Lecture - Directory Coherence Protocol.

- Full Bit-vector:

- Format: The directory maintains a bit-vector for each memory block. Each bit in the vector corresponds to a cache, indicating whether that cache holds the block.

- How to update: On cache states updates, it updates corresponding bit of the block to 0 or 1 according to the new state

- Coarse Bit-vector:

- Format: Caches are grouped into clusters or regions. The directory tracks which clusters have a copy of the block instead of individual caches.

- How to update: If any cache in a group has a copy of a block, the bit value corresponding to the group is set to

1. If the block is not cached anywhere in the group, the bit value is set to0.

- Limited Pointer:

- Format: The directory maintains pointers to a fixed number of sharers (e.g., 2-4 caches). If the number of sharers exceeds this limit, the directory assumes all caches may have the block.

- How to update: If space is available, the directory adds the requesting cache to the list of pointers. If the list is full, it fallback to a broadcast-based invalidation mechanism.

- Sparse Directory:

- Format: The directory stores information for a subset of memory blocks, focusing on blocks currently in use by caches. Blocks without directory entries are assumed uncached.

- How to update: On read miss, if an entry exists for the block, the directory updates it to include the requester. If no entry exists, a new entry is created.

| Scheme | Granularity | Storage Overhead | Update Complexity | Scalability |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Full Bit-Vector | Per Cache | High | Low | Poor for large systems |

| Coarse Vector | Per Cluster | Moderate | Moderate | Good |

| Limited Pointer | Fixed Number | Low to Moderate | Moderate to High | Good for few sharers |

| Sparse Directory | Per Active Block | Low | Moderate to High | Excellent |

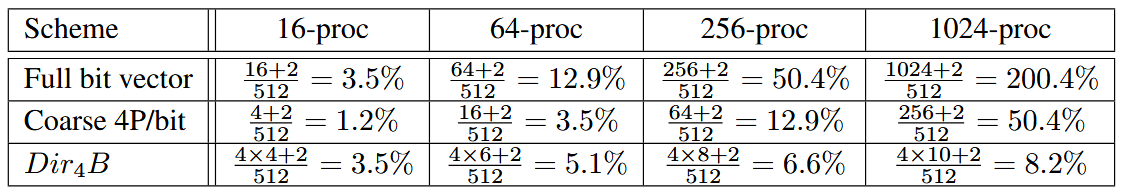

Storage overheads Suppose we have a directory coherence protocol keeping caches coherent. The caches use a 64-byte cache block. Each block requires 2 bits to encode coherence states in the directory. How many bits are required and what is the overhead ratio (number of directory bits divided by block size) to keep the directory information for each block, for full-bit vector, coarse vector with 4 processors/bit, limited pointers with 4 pointers per block? Consider 16, 64, 256, and 1024 caches in the system.

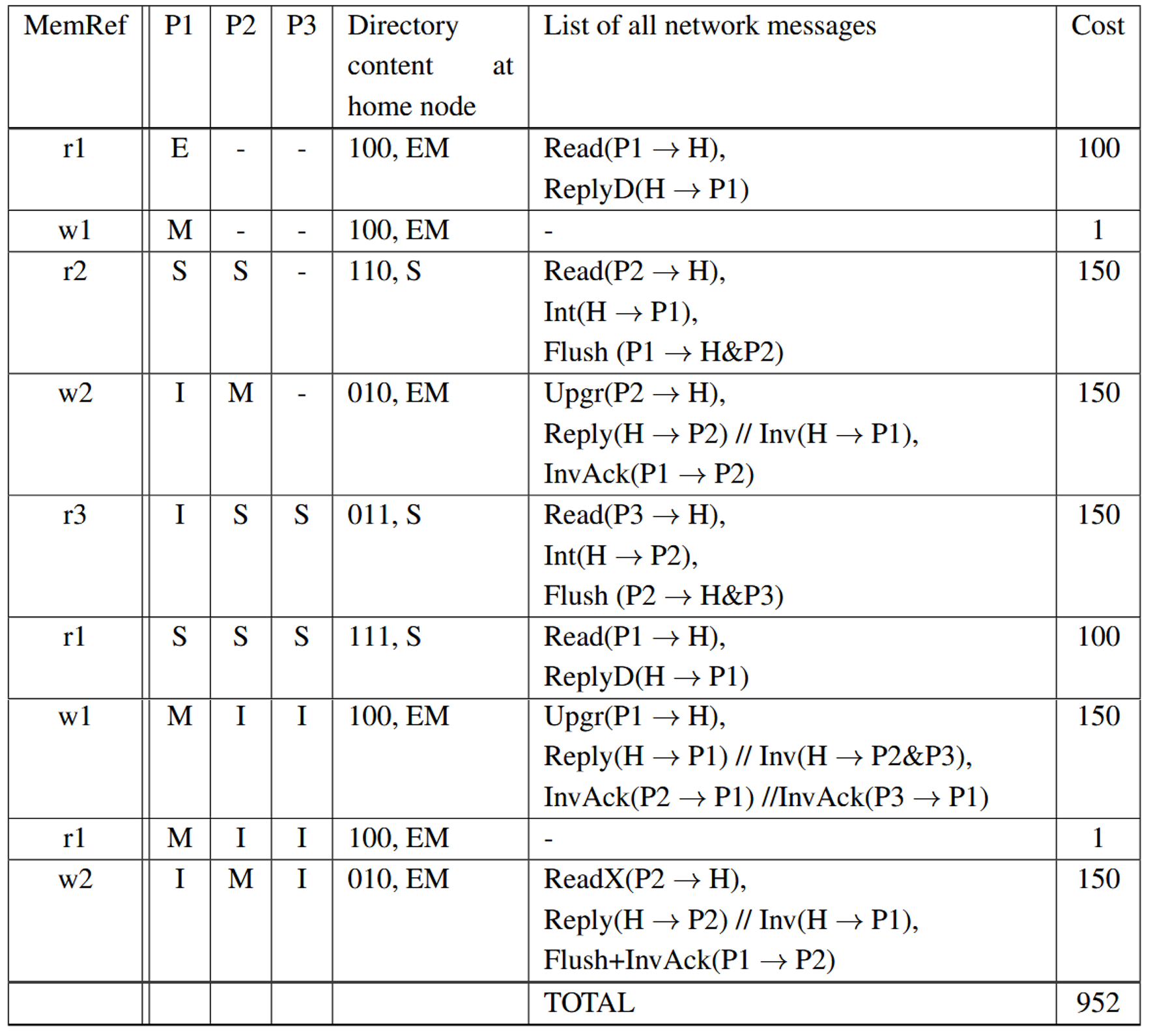

Given a sequence of processor requests in a multiprocessor system using a directory-based protocol, and information about the interconnection network (e.g., topology, latency per hop), show all actions taken and the latency required to satisfy each request, including the state of all caches and the directory after each transaction is completed.

Assume a 3-processor multiprocessor system with directorybased coherence protocol. Assume that the cost of a network transaction is solely determined by the number of sequential protocol hops involved in the transaction. Each hop takes 50 cycles to complete, while a cache hit costs 1 cycle. Furthermore, ignore NACK traffc and speculative replies. The caches keep MESI states, while the directory keep EM (exclusive or modifed), S (shared), and U (uncached) states. Display the state transition of all the 3 caches, the directory content and its state, and the network messages generated for the reference stream shown in the tables.

Demonstrate how a directory state can contain out-of-date information (e.g., as a result of a cache line being silently evicted), and how the protocol handles.

see also "Implementation Correctness and Race Conditions" part in Lecture - Directory Coherence Protocol

A directory state can become out-of-date if a cache line is silently evicted (e.g., due to cache replacement policies) without notifying the directory.

Possible Case

- Initial State:

- Cache C1 and C2 hold a shared copy of a memory block

X. - The directory state for

Xis:- State: Shared

- Sharers: C1, C2

- Cache C1 and C2 hold a shared copy of a memory block

- Silent Eviction:

- Cache C2 evicts block

Xsilently (e.g., due to replacement). - The directory is not informed and still lists C2 as a sharer.

- Cache C2 evicts block

- Subsequent Operation:

- Cache C3 issues a write request to block

X. - The directory believes C1 and C2 still hold shared copies.

- Cache C3 issues a write request to block

- Protocol Action:

- The directory sends invalidation requests to C1 and C2.

- C1 invalidates its copy and acknowledges the directory.

- C2 checks its cache, finds that

Xis no longer present, and may either:- Ignore the invalidation (no action needed), or

- Respond with a "not-present" message to update the directory.

- State Update:

- The directory receives acknowledgments from all relevant caches.

- It updates the sharer list to remove C2 and marks C3 as the exclusive owner.

How to handle

- Robust Acknowledgment Mechanism: The directory relies on acknowledgments from caches to confirm the invalidation. If a cache no longer has the block, it can signal this with a "not-present" or similar response.

- Lazy Updates: If caches do not inform the directory of silent evictions immediately, these are resolved during subsequent operations (e.g., writes or further invalidations).

- Periodic Cleanup (Optional): Some systems include mechanisms for periodic reconciliation between cache states and the directory to proactively correct stale information.

Demonstrate how the directory serves as an ordering point in a cache coherence protocol, and how overlapping requests from multiple caches are processed. Discuss and illustrate differences between the home-centric and requester-assisted approaches.

see also "Implementation Correctness and Race Conditions" in Lecture - Directory Coherence Protocol

When messages that correspond to a request do not happen instantaneously, then it is possible for messages from two different requests to be overlapped.

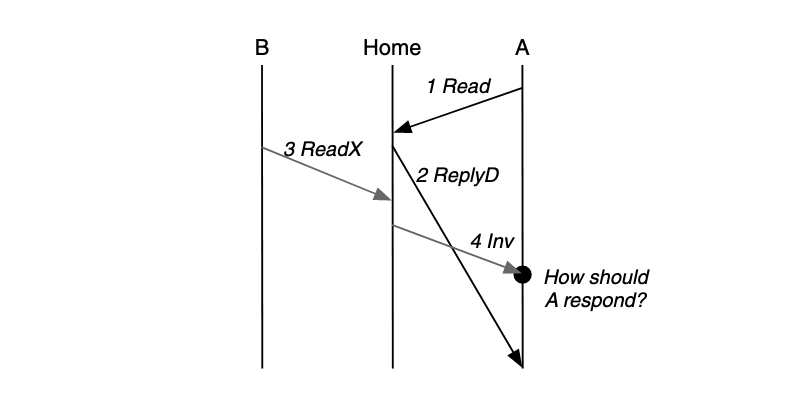

Example: Early Invalidation Race A processor may try to read from a block and another processor may try to write to the block. Both the read and read exclusive requests to the same block may occur simultaneously in the system:

To distinguish when the processing of two requests is overlapped and when it is not, if the end time of the current request processing is greater than the start time of the next request, then their processing is overlapped; otherwise it is not.

To solve overlapping requests,

- Home Centric Approach: Let the directory (home node) determine when the operation is complete, by receiving

Acks from the requester. It must defer or nack other requests to the same block before the current operation complete. - Requestor Assisted Approach: Let the cache controller to track ongoing requests, and only handle conflicting incoming requests after the request is complete. This allows the directory to finish the request earlier because it does not wait for

Ack.

Overlapped processing

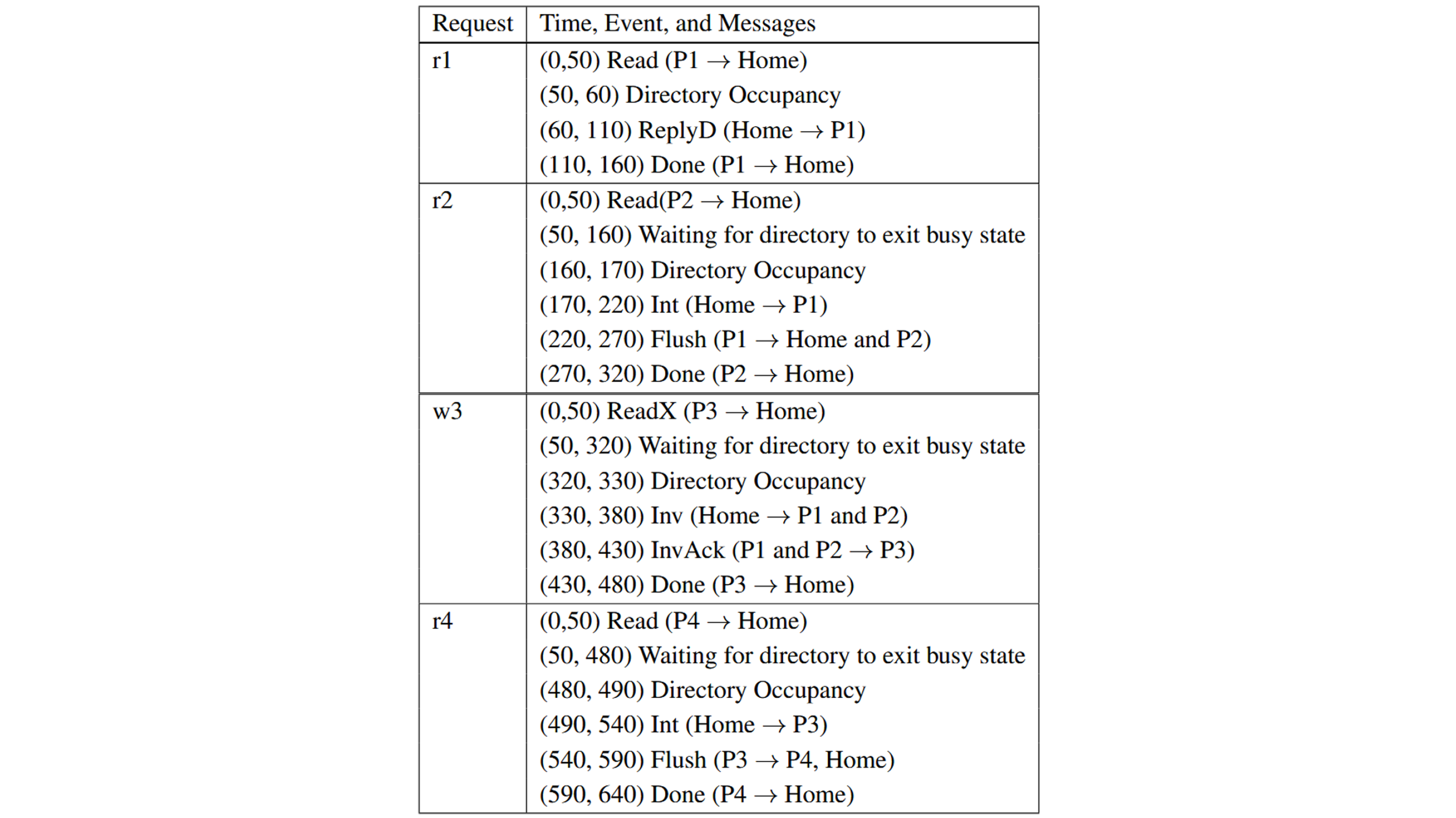

Suppose a 4-processor multiprocessor system uses a directory based coherence protocol with full bit vector. The directory keeps U, EM, and S states, while the caches maintain MESI states. Assume that cost of a network transaction is solely determined by the number of protocol hops involved in the transaction, and each hop has a latency of 50 cycles.

Suppose that a parallel program incurs the following accesses to a single block address: r1, r2, w3, and r4, where r indicates a read request, w indicates a write request, and the number indicates the processor issuing the request. Suppose that the requests are issued simultaneously to the directory at time 0, but the directory receives them in the following order: r1, r2, w3, r4. Assume that the occupancy of the directory (i.e., the length of time the directory looks up and updates the directory state) is 10 cycles, and fetching data from memory incurs 0 cycles.

- What is the latency to complete the processing of all the requests using a home-centric approach?

- What is the latency to complete the processing of all the requests using a requestorassisted approach, which tries to overlap the request processing as much as possible?

Answer: Suppose that r1, r2, w3, and r4 were issued at time 0.

Home-centric approach:

Requestor-assisted approach:

Synchronization

Define and describe different types of synchronization used in parallel programs: mutual exclusion, producer-consumer (events, post-wait), barrier.

- Mutual exclusion: Ensures that only one thread or process can access a critical section (shared resource or code block) at any given time, preventing data races or inconsistencies.

- Producer-Consumer (Events, Post-Wait): Coordinates execution between threads where one (the producer) generates data, and another (the consumer) processes it. Synchronization ensures proper sequencing between production and consumption.

- Events (Signaling): A thread (producer) signals the consumer thread to wake up and consume the data.

- Post-Wait (Semaphores): Producer “posts” (increments) a semaphore to indicate data is ready; consumer “waits” (decrements) the semaphore before consuming.

- Barrier: Ensures that all threads or processes in a parallel program reach a specific point of execution (the barrier) before any of them proceeds. This synchronizes threads to a common point in the program.

| Type | Purpose | Key Mechanisms | Example Use Cases |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mutual Exclusion | Prevent simultaneous access to shared resources. | Locks, Mutexes, Semaphores | Accessing shared counters, file operations. |

| Producer-Consumer | Synchronize production and consumption of data. | Events (Condition Variables), Post-Wait, Buffers | Task queues, data pipelines. |

| Barrier | Synchronize threads at a common execution point. | Centralized counters, Sense Reversal, Messages | Iterative algorithms, phase synchronization. |

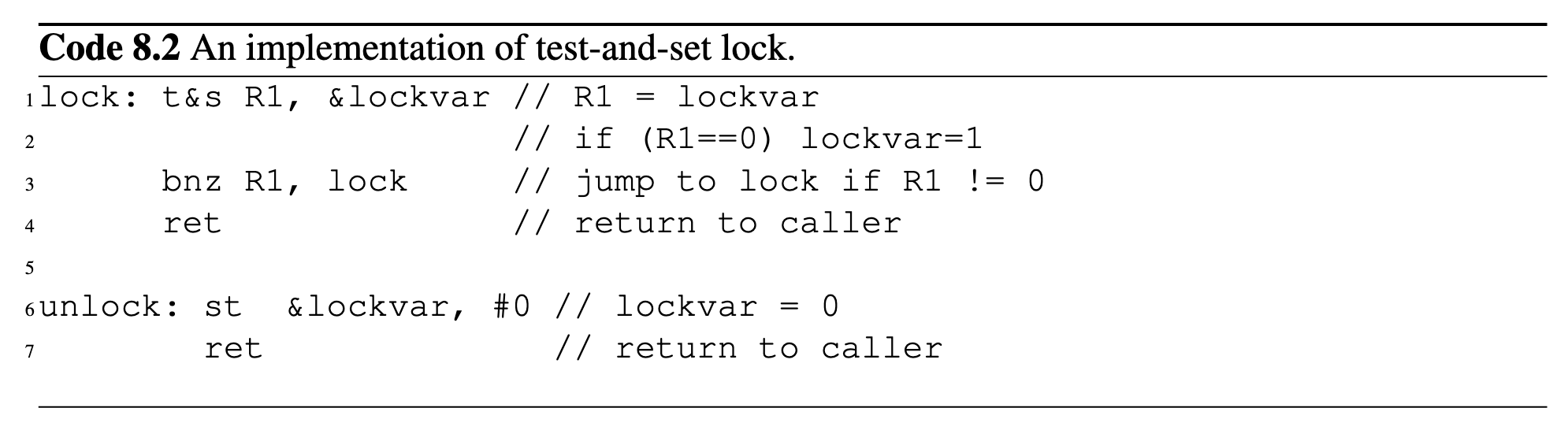

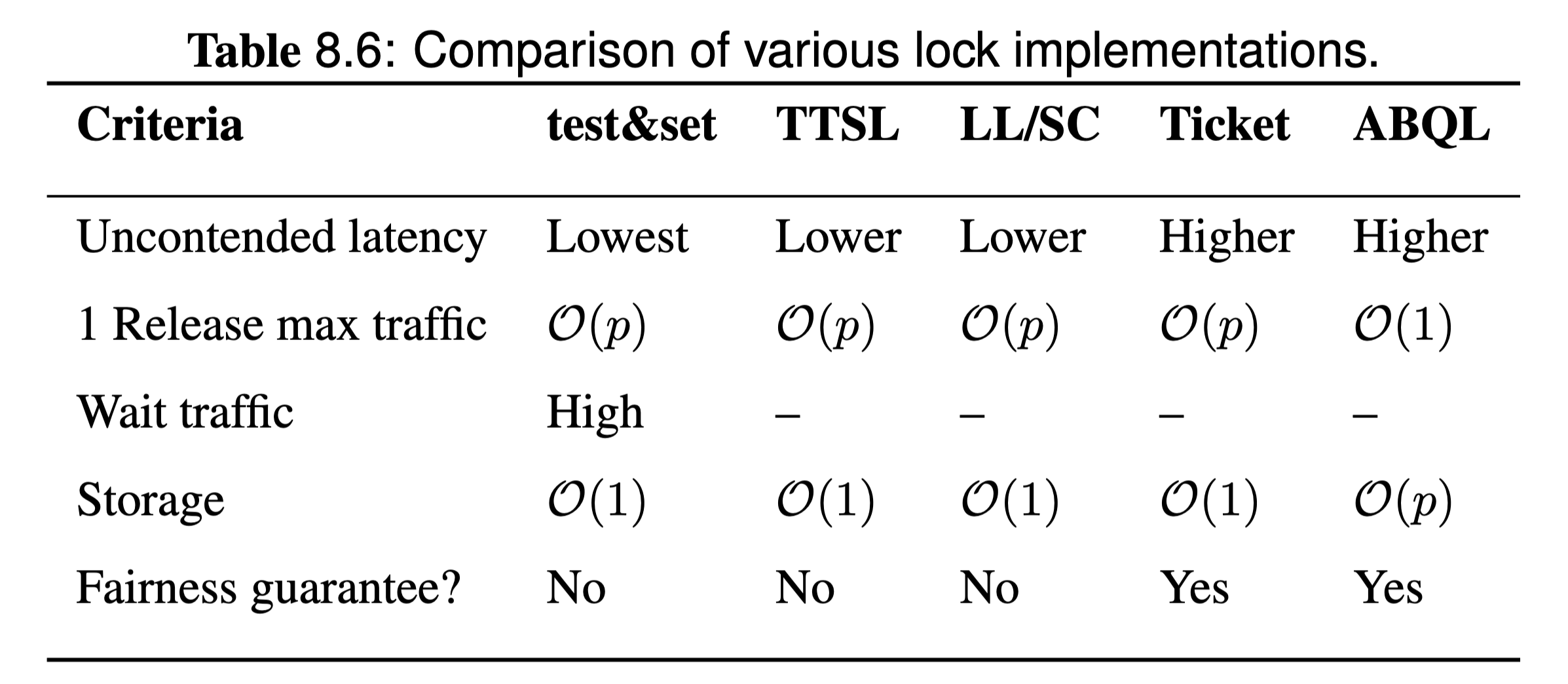

Describe how the atomic test-and-set instruction can be used to implement a mutual exclusion lock. Discuss strategies for reducing coherence traffic, such as using test-and-test-and-set.

Given a cache coherence protocol (snoop- or directory-based), show the memory traffic and latency required to execute a sequence of lock and unlock operations.

see also "Lock Implementation" part in Lecture - Consistency and Synchronization Problems there are also problems related to this topic listed in Homework - 2

test-and-set Rx, M: an atomic instruction that read from M, test to see if it matches some specific value(such as 0), and set it to some value.

Lock:

- A shared variable (e.g.,

lock) is initialized to0(unlocked). - A thread tries to acquire the lock by executing

test-and-set:- If

test-and-set(lock)returns0, the thread acquires the lock (setslock = 1). - If

test-and-set(lock)returns1, the lock is already held, and the thread keeps trying (spinning). Unlock:

- If

- The thread that holds the lock resets

lockto0, allowing other threads to acquire it.

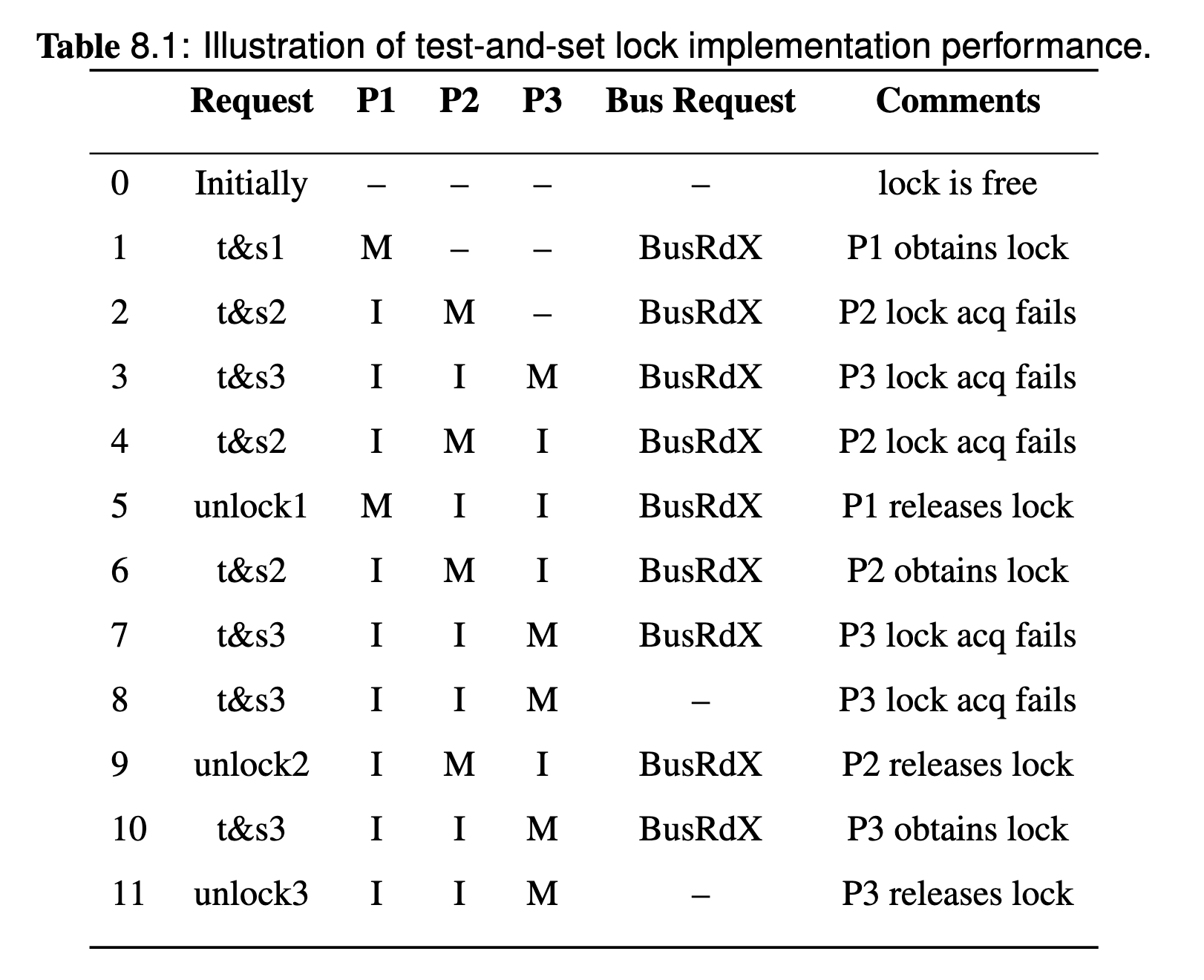

Assume there are 3 threads competing for this lock, the memory coherence and state changes will looks like:

Problem: too much BusRdX too much bandwidth.

Whether the acquisition is successful or not, the bus request is a BusRdX since the atomic test-and-set will try to write(if lock obtain success) after the read and it's a atomic instruction. Therefore, test-and-set lock cause high bus traffic when contending for the lock, it always sending busRdX; it does not maintain fairness; starvation can occur.

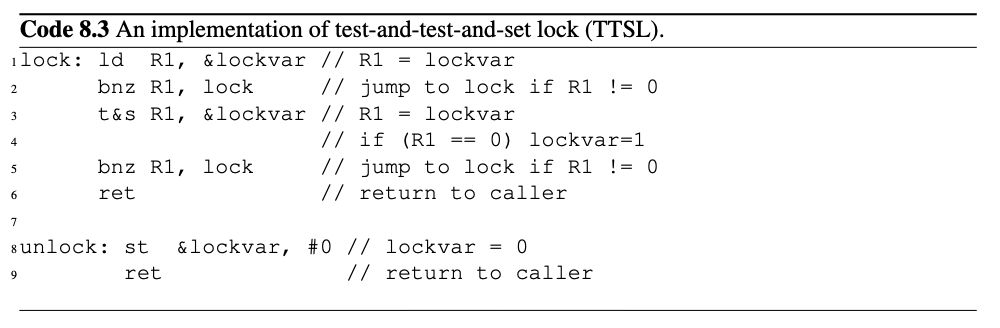

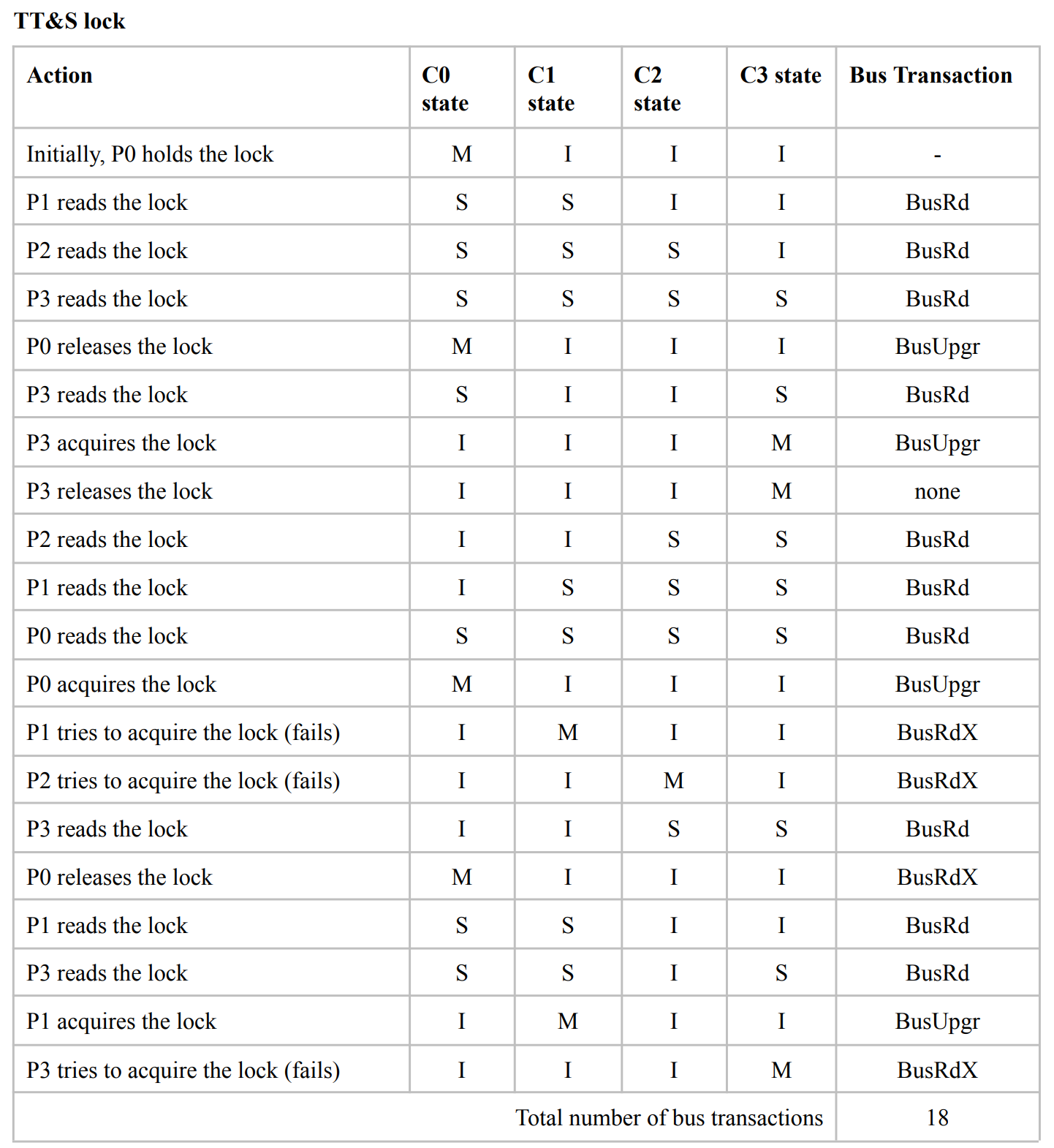

To solve the problem, test-and-test-and-set (TTSL) lock tests whether a lock acquisition attempt will likely lead to failure, and only attempt to obtain the lock if it is likely to success.

TTSL has:

- advantage: significantly reduce bus traffic by replacing

BusRdXwithBusRdin contending situation. - disadvantage: uncontended latency is higher than

test-and-setlock caused by one more load and branch instruction.

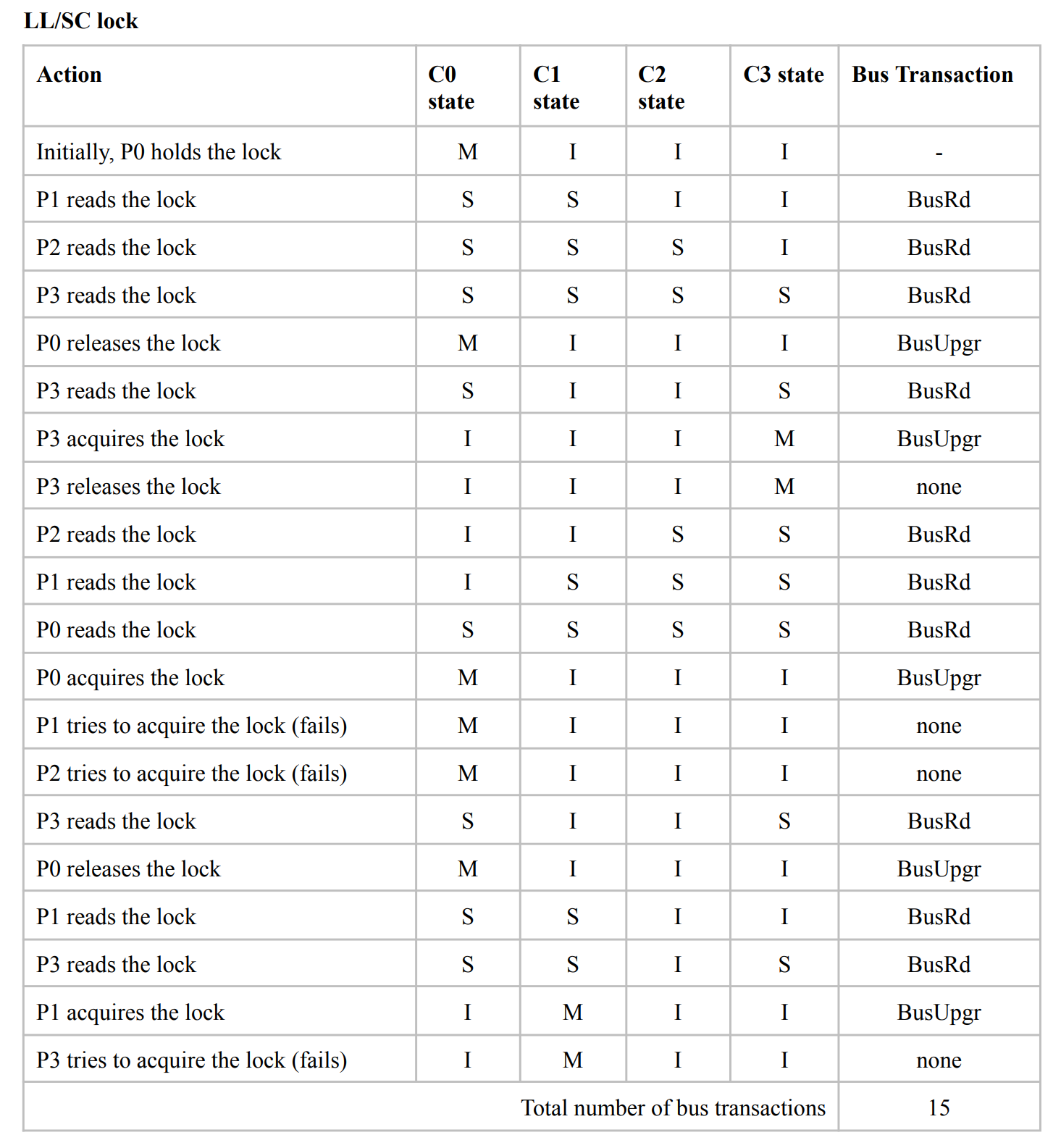

For each action in the sequence below, write the bus transaction required (BusRd, BusRdX, BusUpgr, or None - just the request, not the response), and the state of the block in each cache. The MESI protocol is used for coherence.

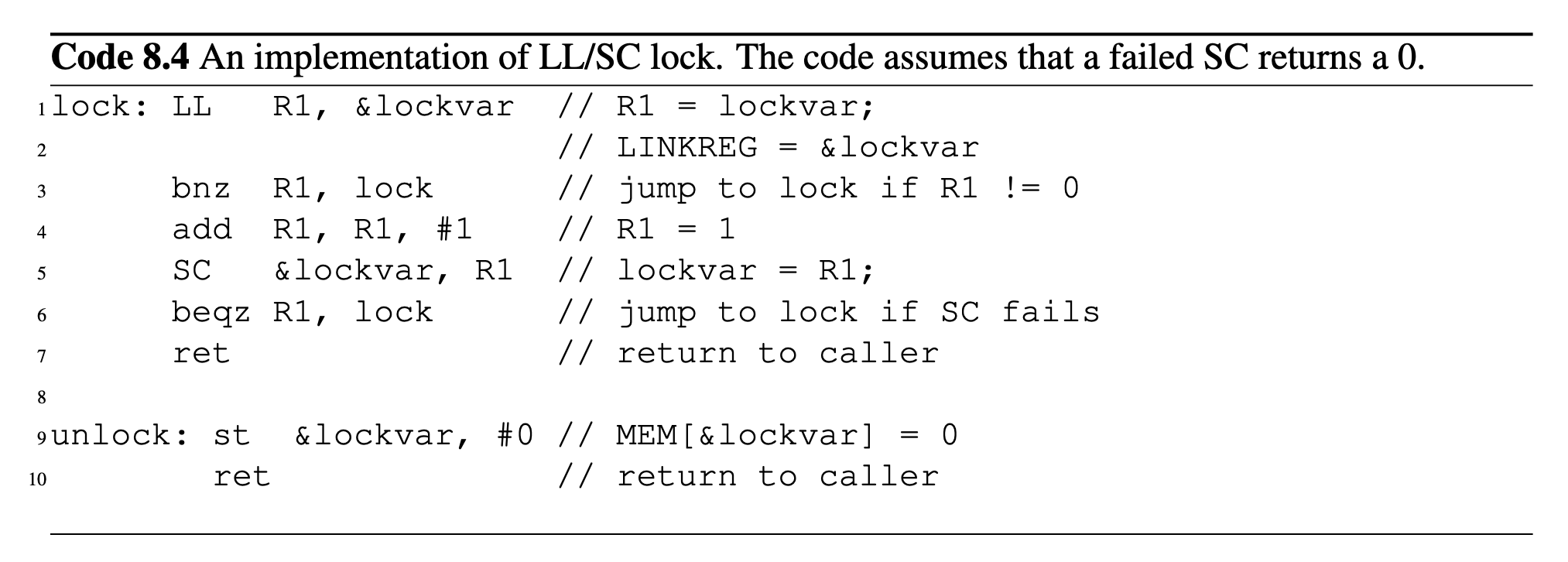

Describe the operation of load-linked and store-conditional instructions.

Given a cache coherence protocol (snoop- or directory-based), show the memory traffic and latency required to execute a sequence of lock and unlock operations.

One way to implement atomic instruction on bus based systems requires a separate bus line that is asserted when a processor is executing an atomic instruction. Load Linked and Store Conditional Lock introduces another perspective of illusion of atomicity and can achieve atomicity without special bus line.

The granularity of TTSL lock is to combine three kinds of instructions load, conditional branch, and store as an atomic instruction. However, LL&SC lock uses an single instruction level granularity, it provides Load Linked (LL) and Store Conditional (SC):

- Load Linked (LL):

- Performs a regular load (read) and marks the memory address or cache line for monitoring, it will be monitored by link register.

- This monitoring ensures that if another processor writes to the same address (or performs any invalidation event), the LL/SC pair will be invalidated.

- Store Conditional (SC):

- Attempts to store (write) a value to the same memory location.

- The store will succeed only if no invalidating events (e.g., writes by other processors, context switches, etc.) occurred to the monitored address since the LL. If an invalidation occurred, the store fails.

If it fails, the store will not happen, and rest of the system cannot see the store and will not even know if it happened. If it is success, other processors will know because the store propagate to the rest of the system.

For each action in the sequence below, write the bus transaction required (BusRd, BusRdX, BusUpgr, or None - just the request, not the response), and the state of the block in each cache. The MESI protocol is used for coherence.

Show how LL/SC Lock can be used to implement atomic operations.

there are also problems related to this topic listed in Homework - 2

Here are some examples generated by ChatGPT

Test-and-Set using LL/SC Test-and-set is used to atomically set a lock and return the old value.

test_and_set:

ll R1, &lockvar // Load linked: R1 = lockvar

bnz R1, test_and_set // If lockvar != 0, retry

mov R2, #1 // R2 = 1 (value to set)

sc R2, &lockvar // Store conditional: lockvar = 1 if no interference

bz R2, test_and_set // If store failed, retry

ret // Return to caller

Compare-and-Swap (CAS) using LL/SC Compare-and-swap atomically sets a value only if it matches an expected value.

compare_and_swap:

ll R1, &lockvar // Load linked: R1 = lockvar

cmp R1, R2 // Compare lockvar with R2 (expected value)

bne R1, fail // If not equal, branch to fail

mov R3, R4 // R3 = new value to set

sc R3, &lockvar // Store conditional: lockvar = R4 if no interference

bz R3, compare_and_swap // If store failed, retry

ret // Return to caller

fail:

ret // Return without updating

Fetch-and-Increment using LL/SC Atomically increments a variable and returns the old value.

fetch_and_increment:

ll R1, &counter // Load linked: R1 = counter

mov R2, R1 // R2 = old value (to return)

addi R1, R1, #1 // Increment R1 by 1

sc R1, &counter // Store conditional: counter = R1 if no interference

bz R1, fetch_and_increment // If store failed, retry

mov R1, R2 // R1 = old value (return value)

ret // Return old value

Describe the ticket-based and array-based implementation of a mutual exclusion lock.

Ticket based lock provide fairness in lock acquisition using queue. Whenever a processor request the lock, it get a corresponding ticket with an (ordering) number, the lock can be obtained and released one by one, when the ticket number matches the next number that can obtain the lock, the processor will get the lock.

However, the current ticket number is maintained by a single variable, every requestor tries to read it, and when someone obtains the lock, every processor gets invalidates.

Array based lock reduces traffic of ticket based lock by using one variable for each processor instead of using a shared one, therefore no invalidation will occur for this ticket variable. It's usually a array with length of number of processors, therefore it's called array-based.

| Ticket Based | Array Based | |

|---|---|---|

| Uncontended lock acquire latency | Single atomic operation + one load. | Single atomic operation + one load. |

| Bus Traffic | Similar to TTS. Waiting = spin in local cache (read). | Lowest of the alternatives. Waiting = spin in local cache (read). Single invalidate and BusRd on release. |

| Fairness | Order of f&inc will determine order of lock acquisition. No starvation. | Order of fetch&inc will determine order of lock acquisition. No starvation. |

| Storage | Two variables - constant. | Highest - array of at least P elements. |

Memory Consistency

Define the concept of a memory consistency model in the context of a shared-memory multiprocessor.

Discuss the properties of each of the following memory consistency models: sequential consistency, weak consistency, release consistency.

Coherence and consistency:

- Memory consistency defines the rules for the order in which memory operations (reads and writes) appear to execute across all processors, ensuring a predictable behavior for shared memory.

- Memory coherence ensures that all processors see a consistent view of a single memory location, meaning writes to a specific memory location are observed in the same order by all processors.

In short: • Consistency: Rules for ordering memory operations across the system. • Coherence: Consistency of a single memory location.

Familiar consistency models:

- Sequential Consistency is the strongest consistency that ensures all memory operations appear to execute in a single, global order called program order, and each of the memory operation should be performed atomically.

- Weak Consistency a.k.a. weak ordering (related to barrier a.k.a. fence) divides operations into synchronization and data operations. It ensures consistency only at synchronization points. It's faster than sequential consistency but requires explicit synchronization.

- Release Consistency (related to critical section) extends weak consistency by splitting synchronization into acquire (before critical section) and release (after critical section). It provides finer-grained control over memory synchronization, improving performance. It only ensures consistency only between acquire and release operations.

Discuss how fence instructions are used to enforce ordering among memory operations. Given a sequence of memory operations under a specified consistency model, show how to introduce a minimum number of fence instructions to achieve a desired ordering outcome.

see also Lecture - Memory Consistency Models

Fence Instruction prohibits the execution of the memory accesses following the fence until all memory accesses preceding the fence have performed. If fence applies to both loads and stores is full fence, if it only applies to stores, it's store fence, otherwise it's load fence.

Thread 1:

x = 1; // (Store to x)

r1 = y; // (Load from y)

Thread 2:

y = 1; // (Store to y)

r2 = x; // (Load from x)

The desired outcome is to ensure that:

x = 1happens-beforer2 = x.y = 1happens-beforer1 = y.

Without fences, a relaxed consistency model might reorder these operations. This could lead to an outcome where both r1 and r2 are 0, violating a program's desired dependency.

Minimal fencing: Thread 1:

x = 1; // (Store to x)

SFENCE; // Ensure store to x is visible

r1 = y; // (Load from y)

Thread 2:

y = 1; // (Store to y)

SFENCE; // Ensure store to y is visible

r2 = x; // (Load from x)

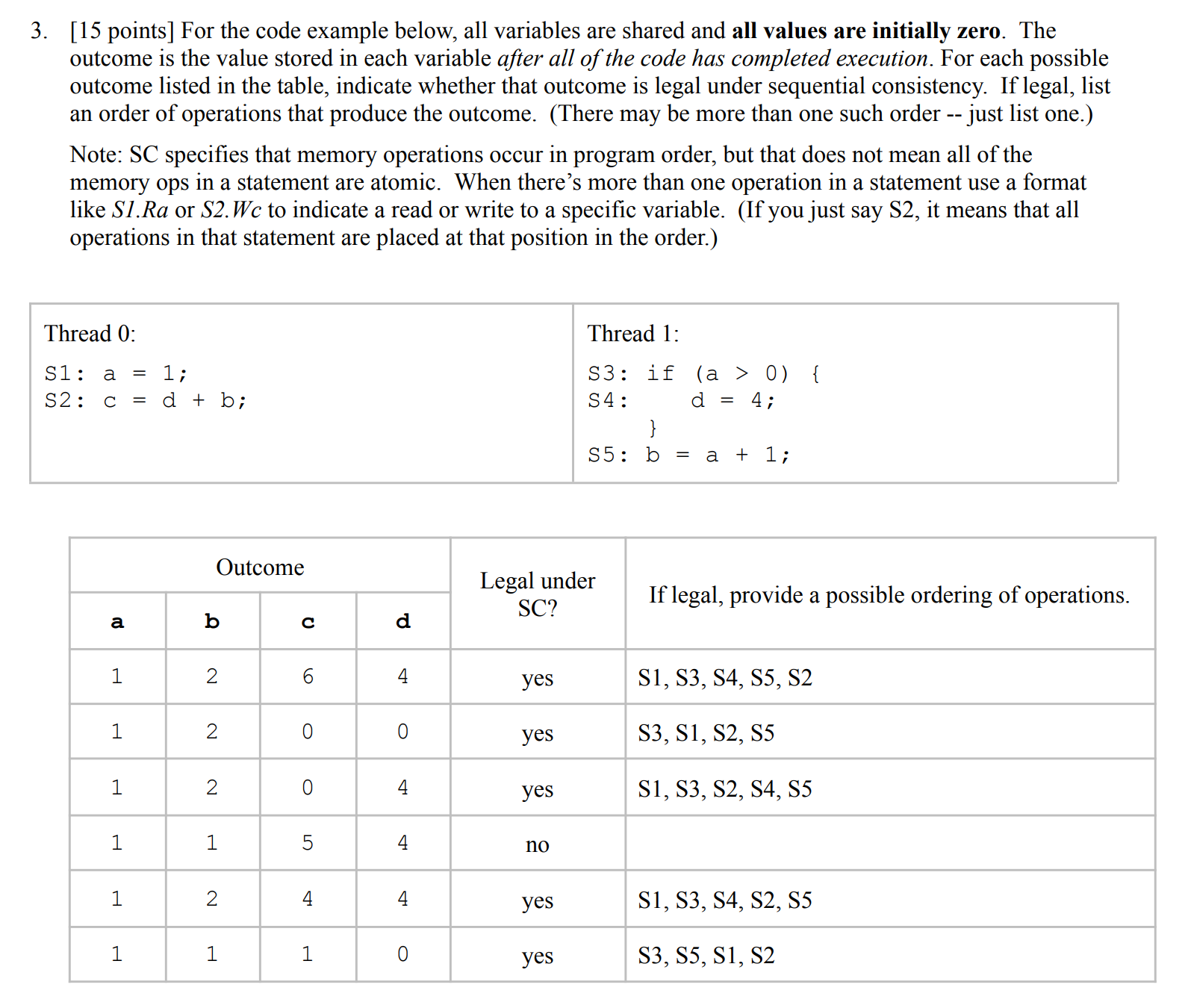

Given a set of variables, their initial values, and a set of memory operations (either as instructions or as C statements), show whether a particular final set of values is allowed under any specified memory consistency model. (Alternatively, show the possible outcomes under a specified model.)

there are also problems related to this topic listed in Homework - 2

Explain the difference between memory consistency and cache coherence.

In multiprocessor systems, consistency is about when changes are visible, and coherence is about what value is seen.

- Cache Coherence deals with the correctness of data values in caches.

- Memory Consistency deals with the ordering of memory operations across processors.

Interconnection Networks

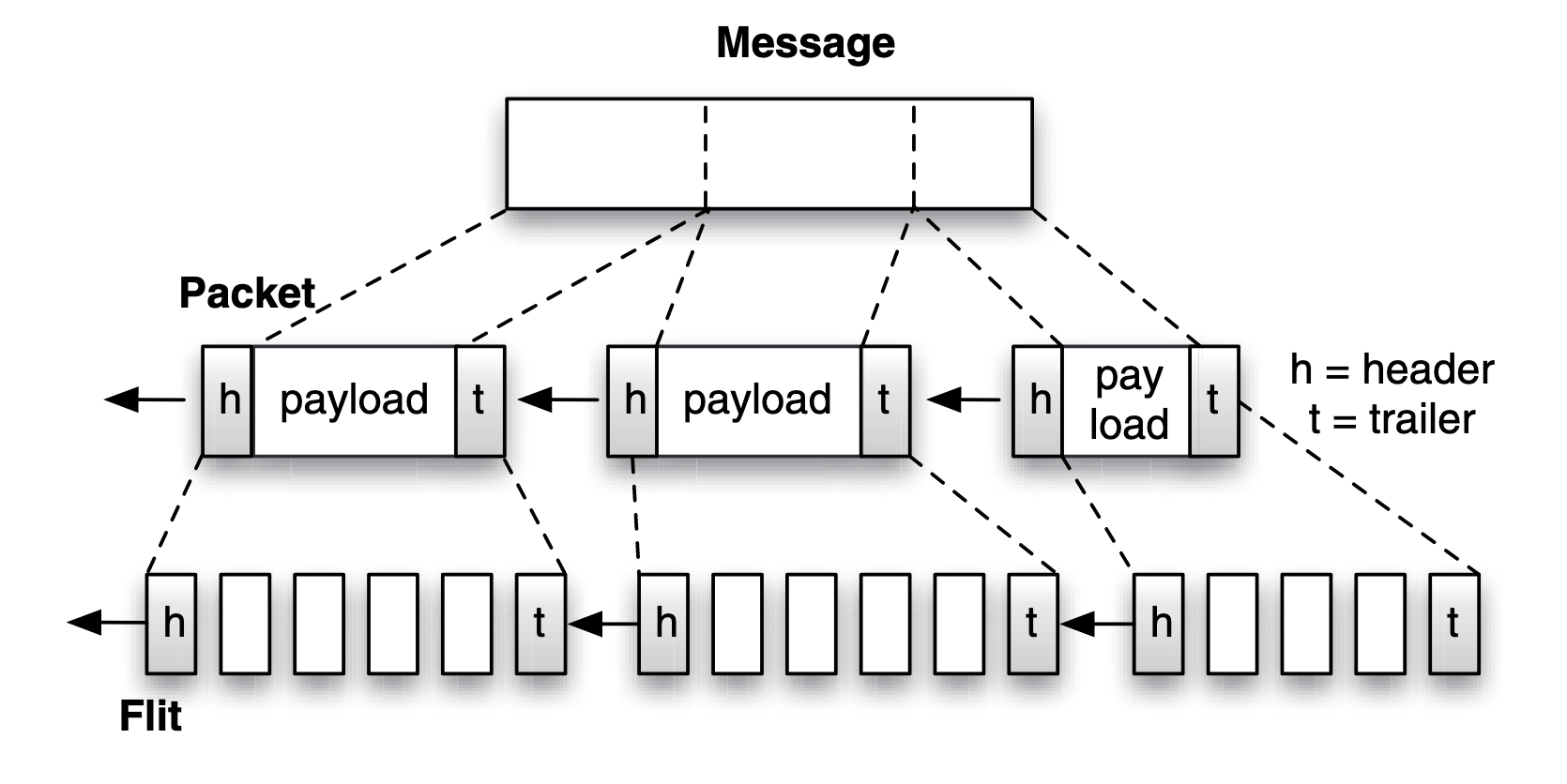

Define the following terms related to multiprocessor interconnection networks: hop, latency, diameter, link bandwidth, bisection bandwidth, topology, routing, flow control, flit, phit, packet.

- Hop: A single traversal of a link between two network nodes or switches.

- Latency: The total time taken for a message to travel from the source to the destination, including transmission, propagation, and processing delays.

- Diameter: The maximum number of hops required to travel between any two nodes in the network.

- Link Bandwidth: The data transfer rate of a single network link, typically measured in bits per second (bps).

- Bisection Bandwidth: The minimum total bandwidth that must be cut to divide the network into two equal halves.

- Topology: The arrangement or structure of nodes and links in a network, such as mesh, torus, or hypercube.

- Routing: The method for determining the path a message will take from source to destination.

- Flow Control: The mechanism for managing data transfer between nodes to avoid congestion or buffer overflows.

- Flit (Flow Control Unit): The smallest unit of data handled by flow control within a network.

- Phit (Physical Transfer Unit): The smallest unit of data that can be physically transferred across a link in a single cycle.

- Packet: A formatted unit of data for transmission, typically composed of multiple flits, including headers and payload.

Describe the delivery of a packet from source to destination using any of the following switching modes: circuit switching, store-and-forward, wormhole.

Given a pair of nodes in a network, the link width, topology, and switching and routing policies, compute the latency for a packet of a given size (without considering any congestion).

- circuit switching, where a connection between a sender and receiver is reserved prior to data being sent over the connection.

- packet switching, when a large message is transmitted on a channel, it is fragmented and encapsulated into packets, the circuit may changes for each packet.

Two routing policy for packet switching:

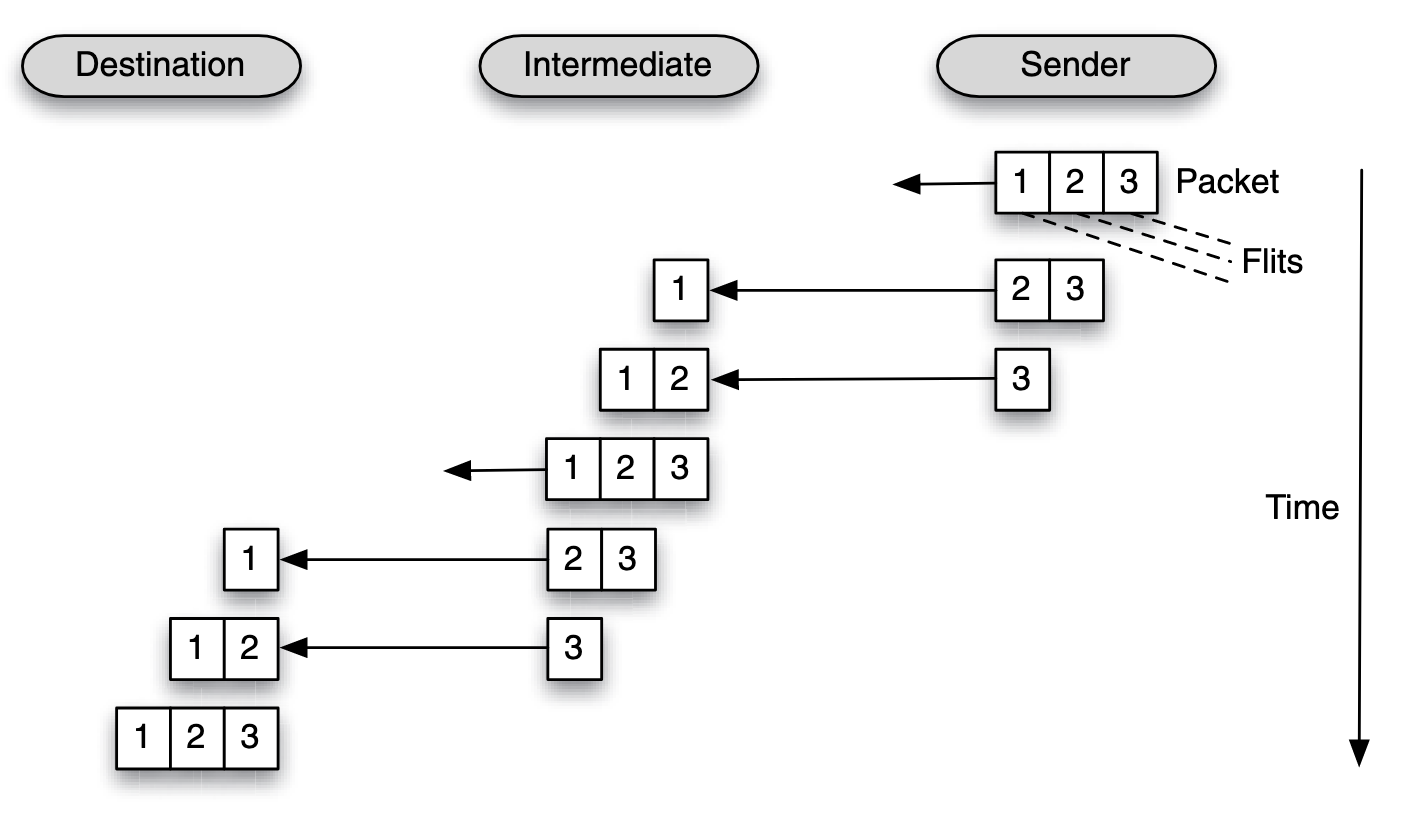

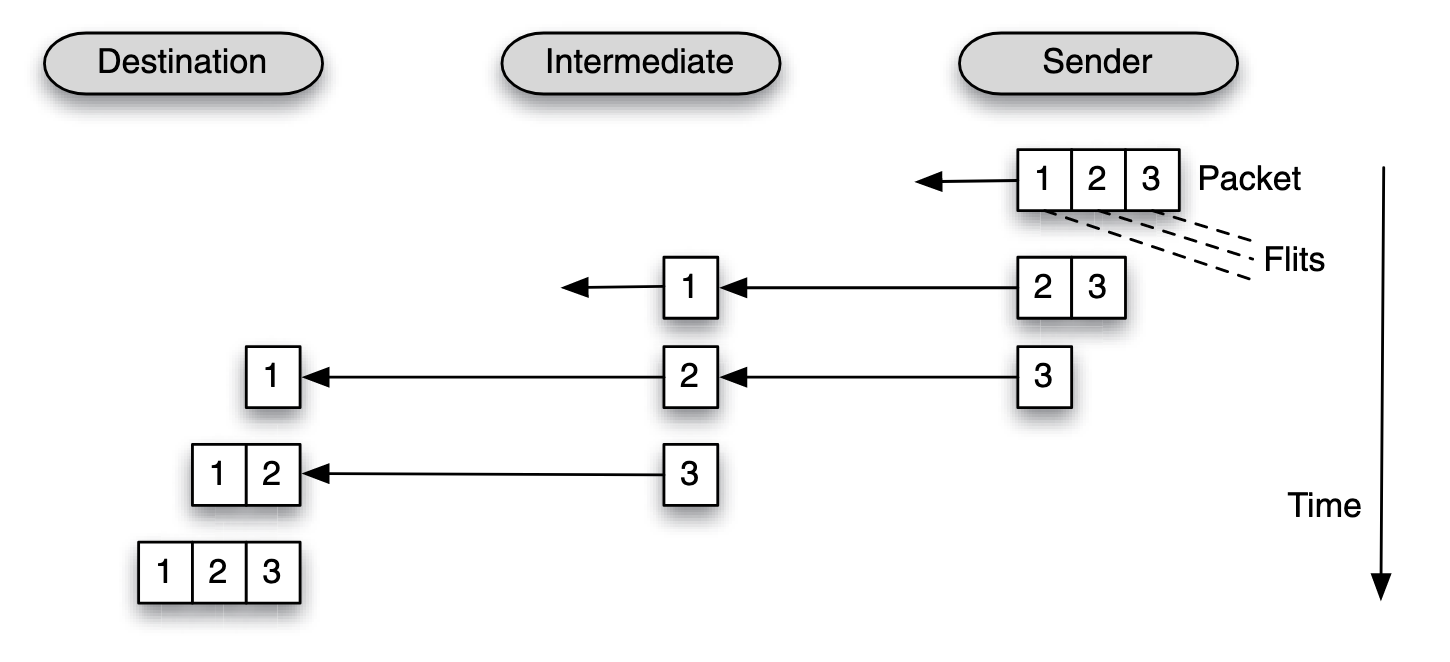

| Aspect | Store-and-Forward Switching | Wormhole Switching |

|---|---|---|

| Figure |  |  |

| Delivery Mechanism | Each intermediate router fully receives and stores the entire packet before forwarding. | Packets are divided into flits; only the header flit is routed, with others following immediately. |

| Latency | High, as each hop incurs the full packet transmission and processing delay. | Low, as only the header incurs routing delay, and flits flow pipeline-style. |

| Buffer Requirements | Large, as the entire packet must be buffered at each hop. | Small, as only a few flits are buffered (e.g., one or two). |

| Congestion Impact | Blocks resources until the entire packet clears, worsening congestion. | May block only portions of a packet, allowing partial progress. |

| Performance | Slower, particularly for large packets or high-diameter networks. | Faster and more efficient, especially for small flits and low-diameter networks. |

| Fault Tolerance | Can retransmit the full packet if an error occurs. | Requires retransmitting the entire packet if any flit is lost. |

Table note: in latency calculation, the first bit has to travel through hops and each hop incurs a routing latency of , then the header latency is , and the serialization latency is .

Familiar network topology:

| Topology | Diameter | Bisection BW | #Links | Degree |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Linear array | 1 | |||

| Ring | 2 | p | ||

| 2-D Mesh | ||||

| Hypercube | ||||

| k-ary d-mesh | ||||

| k-ary Tree | 1 | |||

| k-ary Fat Tree | ||||

| Butterfly |

Diameter represents the maximum number of hops required to send a message in the network. The maximum latency on a specific network topology can be calculated using diameter.

Discuss the properties and implications of various routing protocols: dimension-ordered, adaptive, source routing. You do not need to describe any specific adaptive routing protocol; just demonstrate understanding of the concept. You should be able to apply dimension-order routing for any k-ary n-mesh topology. You should be able to show the application of source routing in any topology.

Routing options:

- Minimal: Chooses the shortest path (fewest hops).

- Non-minimal: Allows longer paths, often to bypass congestion.

- Deterministic: Always selects the same path for a given source-destination pair.

- Non-deterministic: Allows variability in path selection.

- Adaptive: Adjusts paths based on network conditions (e.g., congestion).

- Source Routing: The entire path is precomputed at the source.

- Dimension-ordered: Traverses dimensions (e.g., x, then y, then z) in a fixed order to simplify routing.

The k-ary d-mesh (a.k.a. k-ary n-dimensional mesh) topology is a typical one. For a k-ary d-mesh network, overall there are nodes in the system. The maximum distance in each dimension is one less than the number of nodes in a dimension, i.e., . Since there are dimensions, the diameter of a k-ary d-mesh is . The bisection bandwidth can be obtained by cutting the network into two equal halves. This cut is performed with a plane one dimension less than the mesh, therefore, the bisection bandwidth is .

Hardware Transactional Memory

Describe how hardware transactional memory is used to implement atomic regions in parallel software. Discuss the difference between HTM and LL/SC instructions.

see also Lecture - Transactional Memory

Transactional Memory tracks changes by assigning read/write bits in transactional buffer and detects conflicts via cache coherence protocol.

Conflict detection is naturally achieved via cache coherence protocol. In example above:

- Invalidation for a line in the read set = conflict

- Intervention/invalidation for a line in the write set = conflict

On detecting the conflict, two strategies are:

- eager: detect the conflict on the remote request happens

- lazy: only notified when commit happens

The policy of responding to a conflicts is usually:

- requester wins: Receiver of conflicting request provides data and aborts.

- requester stalls: Receiver either defers (buffers request) or NACKs (requester retries). Requester only aborts if there's a possibility of deadlock.

- committer wins: Someone commit first will win. This is compatible with lazy conflict detection.

On committing and aborting transactions:

- On aborting transaction, it can:

- simply mark all corresponding cache with

Mstate to beIstate, witch will abort all write operations to any address. - Clear R/W bits.

- Signal ABORT to processor, which must rollback execution

- simply mark all corresponding cache with

- On retry, new transaction will load non-speculative data as needed.

| Aspect | Hardware Transactional Memory (HTM) | LL/SC |

|---|---|---|

| Scope | Supports multiple memory locations within a transaction. | Operates on a single memory location. |

| Granularity | Detects conflicts for large memory regions using cache-line tracking. | Limited to a single address with explicit Load/Store operations. |

| Conflict Handling | Detects and handles conflicts automatically. | Relies on retries if the condition (SC succeeds) is violated. |

| Programming Model | High-level abstraction for atomic regions (e.g., transactional blocks). | Requires manual loops and retries around LL/SC operations. |

| Ease of Use | Easier for programmers; reduces explicit locking. | More low-level, requiring careful management. |

| Hardware Requirements | Requires dedicated transactional buffers or cache tracking. | Relatively simpler hardware support. |

Compared to LL/SC instructions mentioned in Lecture - Consistency and Synchronization Problems which is more limited in scope but lightweight and suitable for fine-grained synchronization tasks, transactional memory offers broader support for complex atomic regions and simplifies programming.

Demonstrate how speculative lock elision and transactional lock removal address the issues of version control, conflict detection, and conflict management. Given a sequence of memory and operations in multiple threads, along with instructions that begin and end a transaction, show a sequence of actions performed by the hardware in either of these schemes. (You can disregard the "lock removal" part of the mechanisms, and assume that software explicitly marks the start and end of a transaction.) See the papers by R. Rajwar. You don't need to know all of the details, but be able to give a reasonable description of the major components.

see also Lecture - Transactional Memory

- Version Control: During the transaction, updated values were kept in a speculative buffer and not exposed to other threads. The old version of values remained the officially visible version until commit. Only at commit does the new value become globally visible. This allows the hardware to roll back easily if a conflict occurs, reverting to the old versions without complicated software routines.

- Conflict Detection and Conflict Management: offered by transactional memory

Consider two threads performing operations on a shared variable x using a lock.

Pseudo-Code:

Thread 1: Thread 2:

lock(L); lock(L);

x = x + 1; x = x + 2;

unlock(L); unlock(L);

- Start Transaction: Both threads detect the lock operation and treat it as a transactional start.

- Speculative Execution:

- Each thread executes the critical section speculatively.

- Hardware tracks memory operations (

xandL) in the cache.

- Conflict Detection:

- If

Thread 1writesxwhileThread 2is also accessingx, the cache coherence protocol detects the conflict.

- If

- Conflict Management:

- Abort: One thread (e.g.,

Thread 2) aborts its transaction. - Retry: The aborted thread retries, either re-entering the speculative region or falling back to the lock.

- Abort: One thread (e.g.,

SIMT Architecture

Define the following terms, in the context of SIMT processing: grid, thread block, thread, warp.

In the context of SIMT (Single Instruction, Multiple Threads) processing:

- Grid: A grid is the highest-level structure that organizes thread blocks in a kernel launch. It represents the entire workload, with thread blocks forming its elements. A grid can be one, two, or three-dimensional.

- Thread Block: A thread block is a group of threads that execute together and can share resources like shared memory and synchronize via barriers. It is a subdivision of the grid and can also be one, two, or three-dimensional.

- Thread: A thread is the smallest unit of execution in SIMT processing. Each thread executes independently, following its program logic, but many threads execute in parallel within a thread block and across thread blocks.

- Warp: A warp is a group of threads (typically 32 in CUDA) that execute the same instruction at the same time in lockstep. It is the smallest unit of execution scheduling on a GPU. Divergence within a warp can cause performance inefficiencies.

Demonstrate understanding of SIMT software, using the CUDA syntax. For this topic, I will not ask you to write your own CUDA code, but you should be able to interpret code and explain what computation will be performed. Specifically:

a. Using __global__ to identify a kernel function.

b. Using the blockIdx and threadIdx variables to uniquely identify a thread and to access specified elements of shared data.

c. Using the <<<...>>> notation to specify the number of threads and their organization when calling a kernel function.

d. Using __shared__ to allocate variables in the shared memory address space.

e. You will not be asked to allocate global memory or copy memory between the CPU and GPU.

Using blockIdx and threadIdx

__global__ void multiplyKernel(int *data, int multiplier) {

int idx = blockIdx.x * blockDim.x + threadIdx.x; // Global thread index

data[idx] *= multiplier; // Multiply each element by the multiplier

}

blockIdx.xidentifies the block index.threadIdx.xidentifies the thread index within a block.blockDim.xgives the number of threads per block, which helps calculate the unique global index for each thread.

Using <<<...>>> to specify threads and their organization

The <<<blocks, threads>>> syntax specifies the number of thread blocks and the number of threads per block.

int main() {

int dataSize = 1024;

int threadsPerBlock = 256;

int blocks = (dataSize + threadsPerBlock - 1) / threadsPerBlock;

multiplyKernel<<<blocks, threadsPerBlock>>>(deviceData, multiplier);

}

- In this example,

multiplyKernelis launched withblocksthread blocks, each containingthreadsPerBlockthreads. - Together, the threads cover all elements in the array.

Using __shared__ to allocate shared memory

Shared memory is allocated per block and is accessible to all threads in the block.

__global__ void sumKernel(int *input, int *output, int n) {

__shared__ int sharedData[256]; // Allocate shared memory

int idx = threadIdx.x + blockIdx.x * blockDim.x;

// Load input into shared memory

if (idx < n) sharedData[threadIdx.x] = input[idx];

__syncthreads(); // Ensure all threads have written to shared memory

// Simple reduction (sum)

if (threadIdx.x == 0) {

int blockSum = 0;

for (int i = 0; i < blockDim.x; i++) {

blockSum += sharedData[i];

}

output[blockIdx.x] = blockSum;

}

}

__shared__creates a shared array for temporary storage.__syncthreads()ensures all threads in the block synchronize before proceeding to avoid race conditions.

Explain how conditional and iterative code is executed when different threads take divergent paths

When threads in a group (warp) encounter a conditional (e.g., if-else):

- Predicate Evaluation: Each thread evaluates the condition independently.

- Execution Masking:

- Threads taking the true branch are marked active; others are inactive.

- The processor executes the instructions for the true branch, ignoring inactive threads.

- Then, it switches to the false branch, activating the other threads and executing their instructions.

- Serial Execution: Both paths are executed serially for the divergent threads, reducing parallel efficiency.

For loops where threads iterate a different number of times:

- Threads continue execution until their condition becomes false.

- Threads that finish earlier remain idle (inactive) until all threads complete.