Directory Coherence Protocol

Directory Based Cache Protocol

Directory coherence protocol avoids large broadcasting traffic in broadcast/snoopy protocols. In a directory approach, the information about which caches have a copy of a block is maintained in a structure called the directory.

Physically the directory can be on chip, in cache, but logically directory is not cache, it is logically aside of cache. The directory must know:

- which cache(s) keeps a copy of the block

- in what state the block is cached.

Basic Directory Cache Coherence Protocol

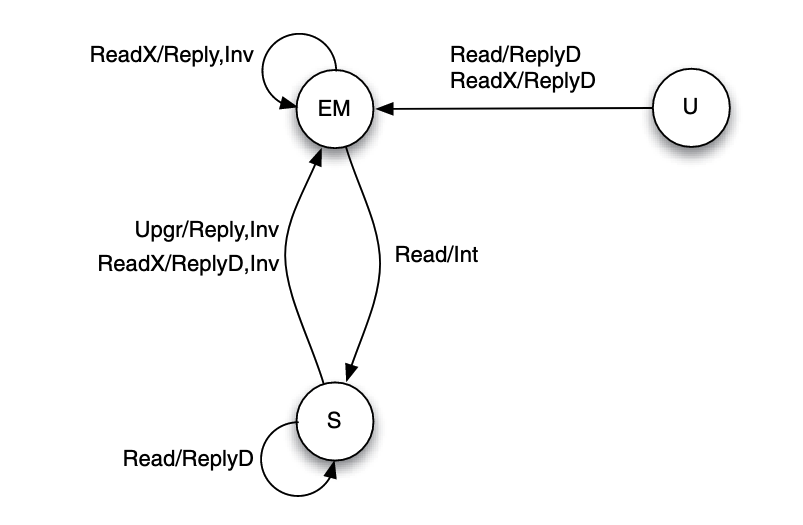

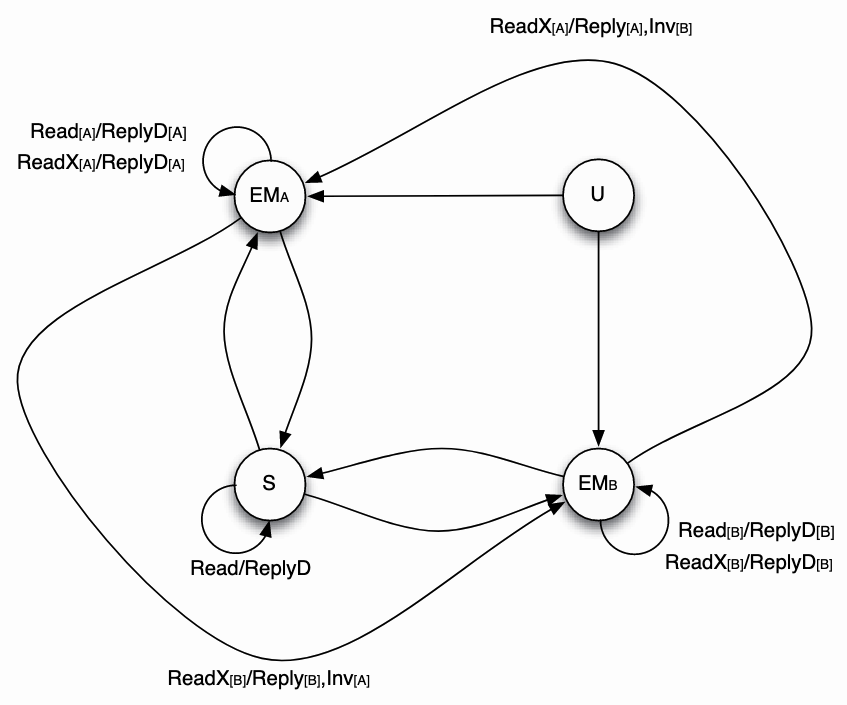

Assuming basic MESI protocol, since the block state is changed from exclusive to modified state silently, thus the directory cannot distinguish between E and M states, to cater to MESI cache states, it can keep exclusive/modified (EM) as a single state:

- Exclusive or Modified (EM): the block is either cached in exclusive or modified state in only one cache.

- Shared (S): the block is cached cleanly, possibly by multiple caches.

- Uncached (U): the block is uncached or cached in invalidate state.

Request types used:

- Read: read request from a processor.

- ReadX: read exclusive (write) request from a processor that does not already have the block.

- Upgr: request to upgrade the state of a block from shared to modified, made by a processor that already has the block in its cache.

- ReplyD: reply from the home to the requester containing the data value of a memory block.

- Reply: reply from the home to the requester not containing the data value of a memory block.

- Inv: an invalidation request sent by the home node to caches.

- Int: an intervention (downgrade to state shared) request sent by the home node to caches.

- Flush: the owner of a cache block sends out its cached data block.

- InvAck: acknowledgment of the receipt of an invalidation request.

- Ack: acknowledgment of the receipt of non-invalidation messages.

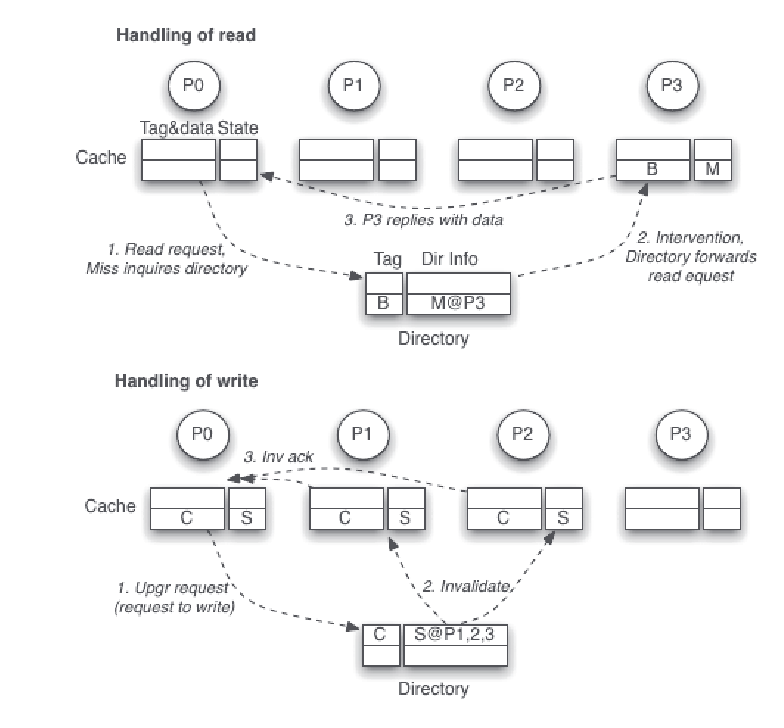

On cache read miss:

The requester will send a Read(for PrRd) to directory. Then the directory checks the block's status:

- if the block is in uncached

Ustate, it fetches the block from memory and sends a reply with dataReplyDto the requester, and it transactions toEMstate. - if the block is in shared

Sstate, it sends a copy of the block withReplyDand update the record to indicate that the requester has the block too. - If the block is in modified

Mstate, the directory instructs the owning cache to write back the block to memory by sending a intervention requestIntto it, and the intervention request also contains the ID of the requester so that the owner knows where to send the block, so it sends aReplyDto the requester.

On cache write miss:

The requester will send a ReadX(for PrWr) to directory. Then the directory checks the block's status:

- if the block is in shared

Sstate, the directory sends invalidation requestInvto shared holders, and update the record to indicate that the requester has the block inMstate. - if the block in modified

Mstate, the directory also send invalidation, but the target cache will do a write-back if applicable, or forward it to the requester, then all other copies will be invalidated.

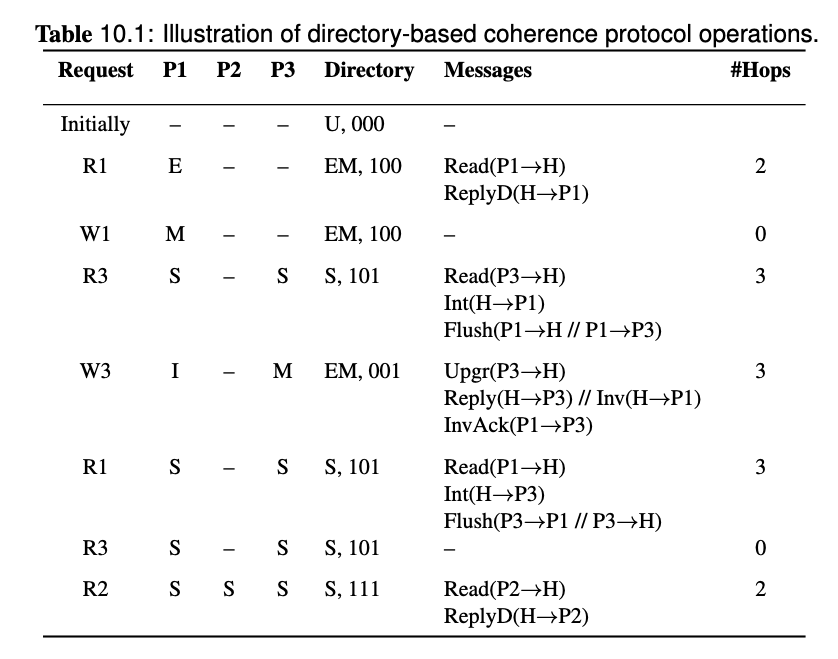

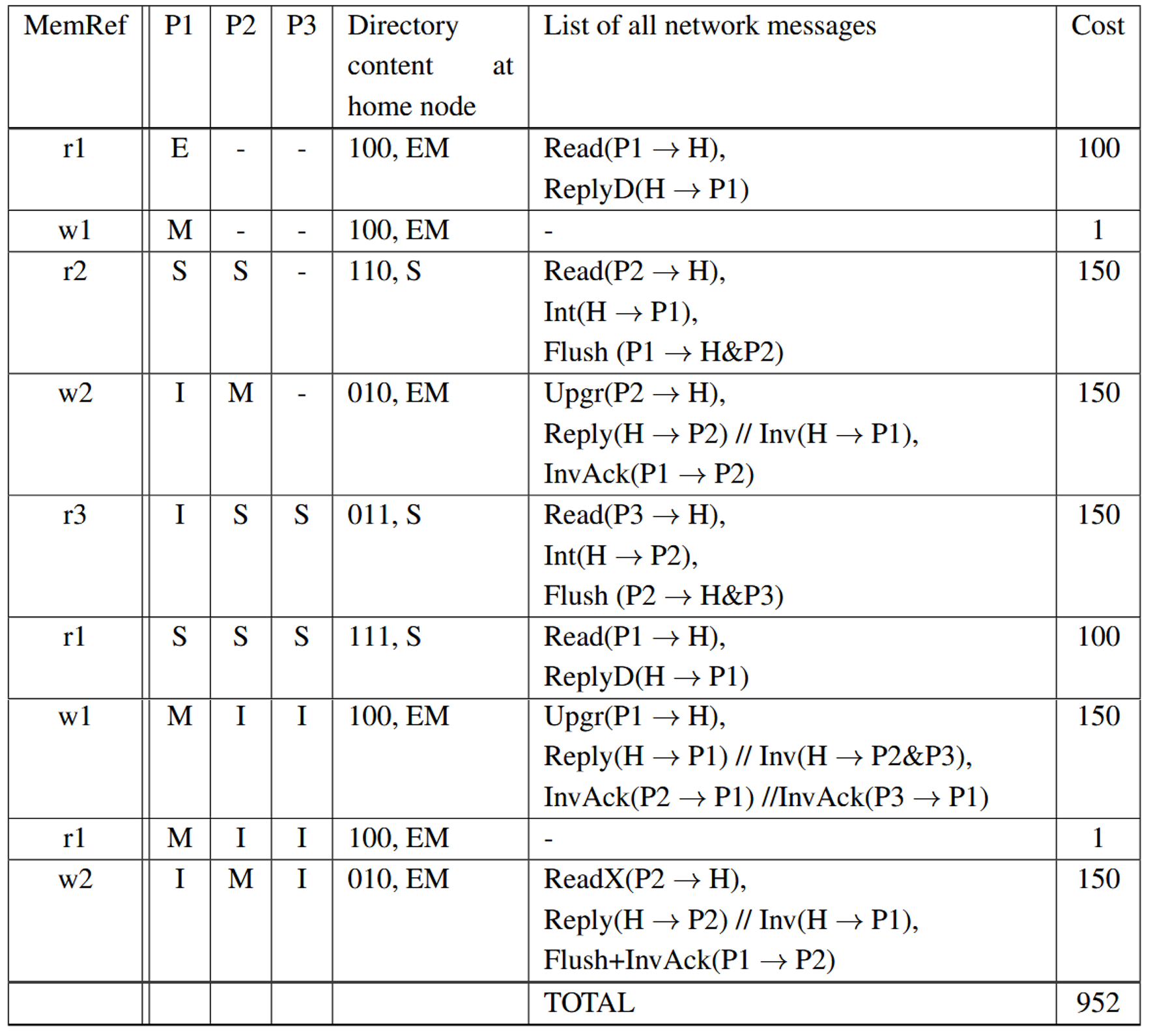

Assume a 3-processor multiprocessor system with directorybased coherence protocol. Assume that the cost of a network transaction is solely determined by the number of sequential protocol hops involved in the transaction. Each hop takes 50 cycles to complete, while a cache hit costs 1 cycle. Furthermore, ignore NACK traffc and speculative replies. The caches keep MESI states, while the directory keep EM (exclusive or modifed), S (shared), and U (uncached) states. Display the state transition of all the 3 caches, the directory content and its state, and the network messages generated for the reference stream shown in the tables.

Write Propagation

Write propagation is achieved by sending all requests to directory, which will then send invalidations to all sharers. On a miss, the directory provides the most recently written data by either:

- retrieving from memory

- or sending an intervention to the cache that owns a dirty block.

Transaction Serialization

Transaction serialization is achieved by making sure that all requests appear to complete in the order in which they are received (and accepted) by the directory. Stalling can be done by NACK or by buffering requests.

Storage Overheads

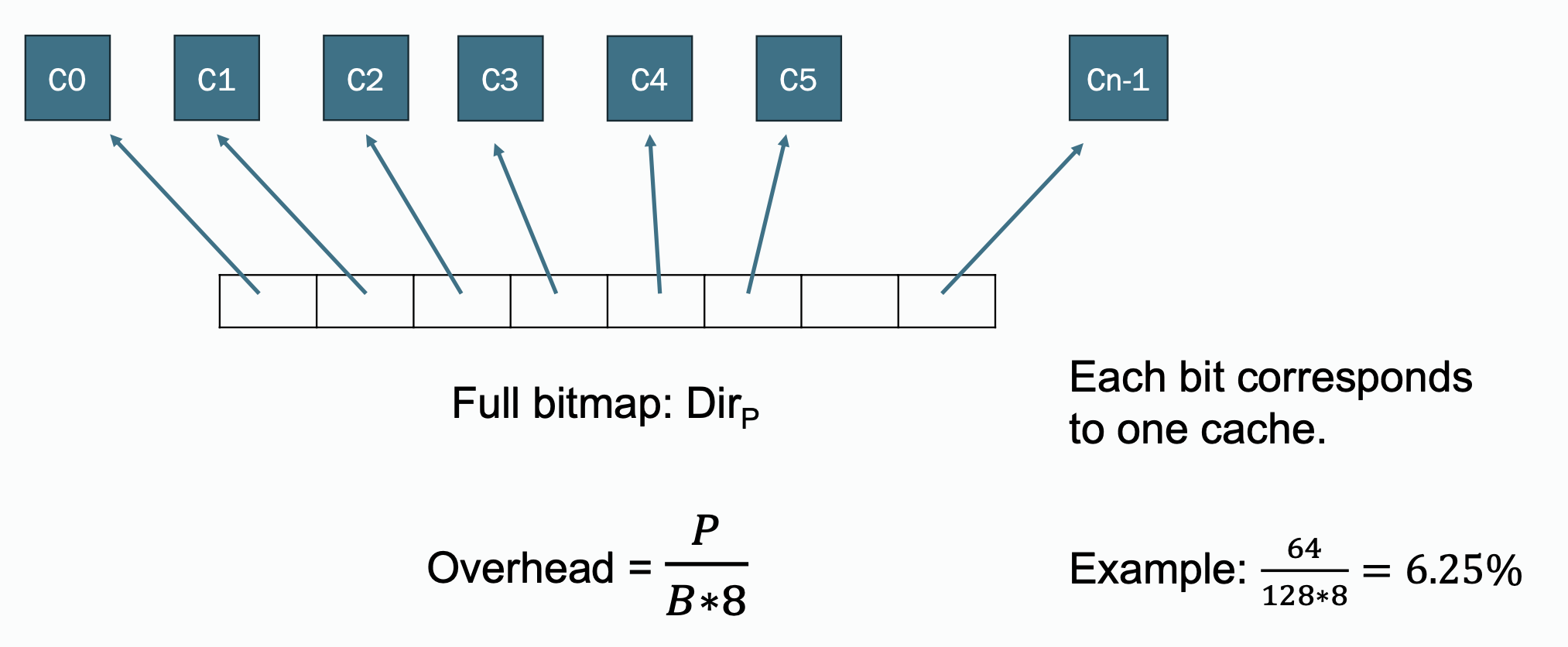

Full Bit Vector Format

The directory maintains a bit-vector for each memory block. Each bit in the vector corresponds to a cache, indicating whether that cache holds the block. On cache states updates, it updates corresponding bit of the block to 0 or 1 according to the new state

If there are p caches, each block in memory then requires p bits of information. The ratio of directory storage overhead to the storage for a data block grows linearly with the number of caches.

Assuming a cache block size of 64 bytes, when there are 64 caches, the storage overhead ratio is

Its simple and precise; supports any number of sharers, but the space overhead grows linearly with the number of caches. The overhead can be quite high for a larger machine.

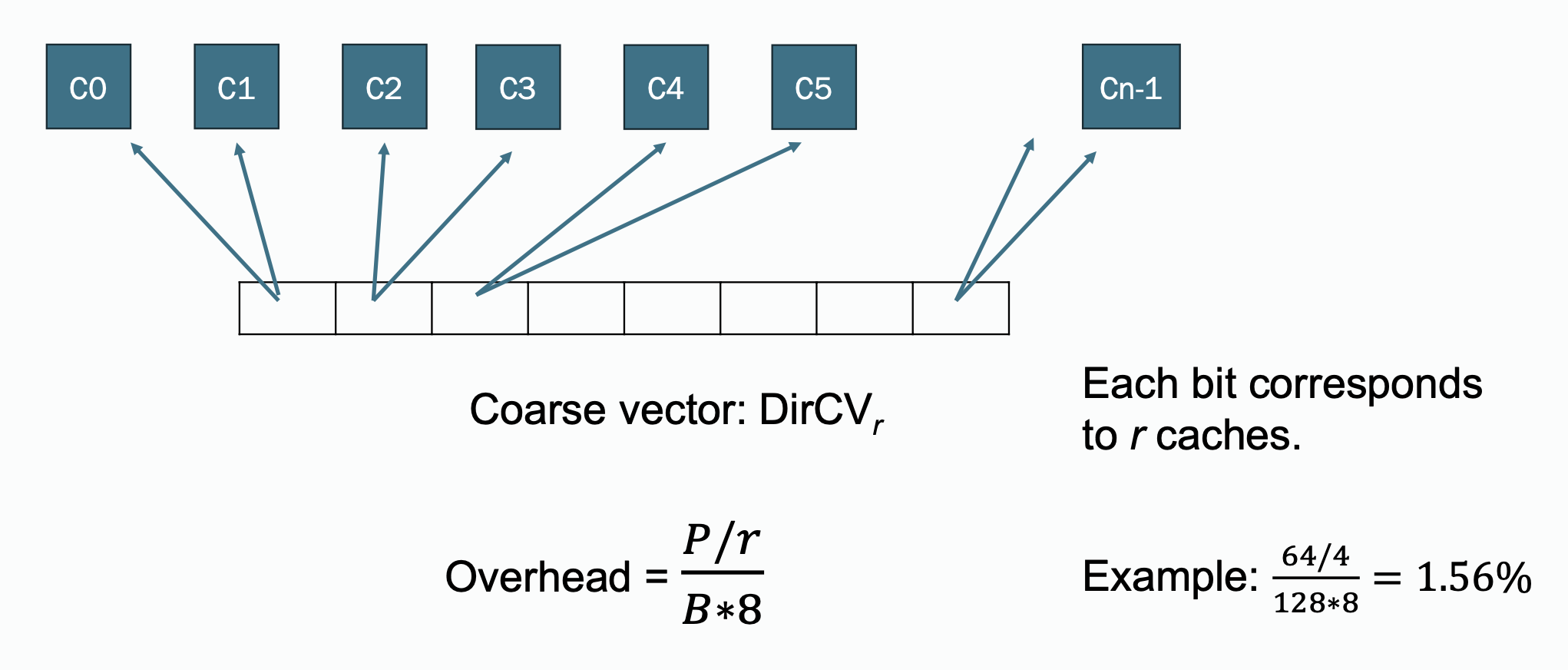

Coarse Bit Vector Directory Format

Caches are grouped into clusters or regions. The directory tracks which clusters have a copy of the block instead of individual caches.

If any cache in a group has a copy of a block, the bit value corresponding to the group is set to 1. If the block is not cached anywhere in the group, the bit value is set to 0.

This format reduces storage overhead by tracking clusters rather than individual caches.

Traffic increases compared to the full bit vector approach. Since the information is kept per group, when there is an invalidation, the invalidation must be sent to all caches in the group, even when only one cache in the group has the block.

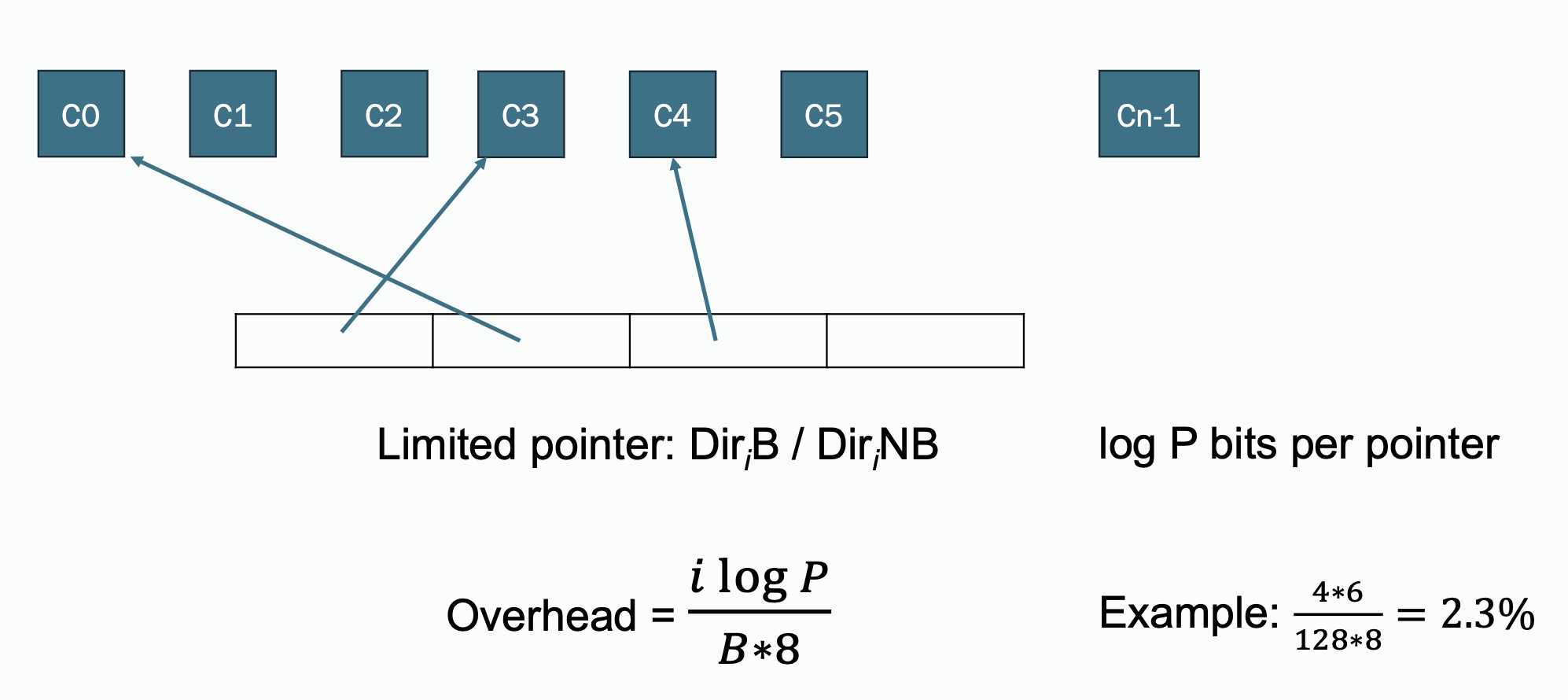

Limited Pointer Format

The directory maintains pointers to a fixed number of sharers (e.g., 2-4 caches). If the number of sharers exceeds this limit, the directory assumes all caches may have the block.

This strategy provides a tradeoff that improves performance when space is available and fallback to broadcast when not:

- If space is available, the directory adds the requesting cache to the list of pointers.

- If the list is full, it transitions to a broadcast-based invalidation mechanism.

One question is in the rare case in which the number of sharers is larger than the number of pointers. One strategy is to not allow the case to occur: when there is a cache which wants to keep a copy of a block, the directory sends an invalidation to a cache that currently keeps a copy of a block to make a room to store the ID of the new cache.

This strategy can backfire when the reason that there are many sharers of a block is because the block contains data used for global synchronization, such as a centralized barrier. Other strategies, such as reverting to broadcast when the number of sharers exceeds the number of pointers, suffers from a similar problem.

Sparse Directory Format

The directory stores information for a subset of memory blocks, focusing on blocks currently in use by caches. Blocks without directory entries are assumed uncached. On read miss, if an entry exists for the block, the directory updates it to include the requester. If no entry exists, a new entry is created.

The storage overhead is relatively low compared to full bit one, it only active blocks require directory entries.

There is a risk of overflow. This is because a clean block may be replaced silently from the cache, without notifying the directory cache. Thus, the directory cache may still keep the directory entry for the block, preventing the entry from being used for a block that may actually be cached.

| Scheme | Granularity | Storage Overhead | Update Complexity | Scalability |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Full Bit-Vector | Per Cache | High | Low | Poor for large systems |

| Coarse Vector | Per Cluster | Moderate | Moderate | Good |

| Limited Pointer | Fixed Number | Low to Moderate | Moderate to High | Good for few sharers |

| Sparse Directory | Per Active Block | Low | Moderate to High | Excellent |

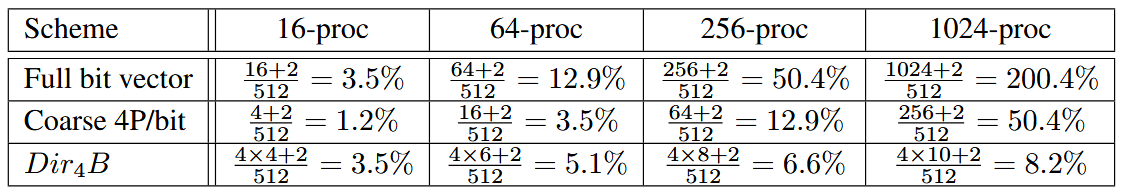

Storage overheads Suppose we have a directory coherence protocol keeping caches coherent. The caches use a 64-byte cache block. Each block requires 2 bits to encode coherence states in the directory. How many bits are required and what is the overhead ratio (number of directory bits divided by block size) to keep the directory information for each block, for full-bit vector, coarse vector with 4 processors/bit, limited pointers with 4 pointers per block? Consider 16, 64, 256, and 1024 caches in the system.

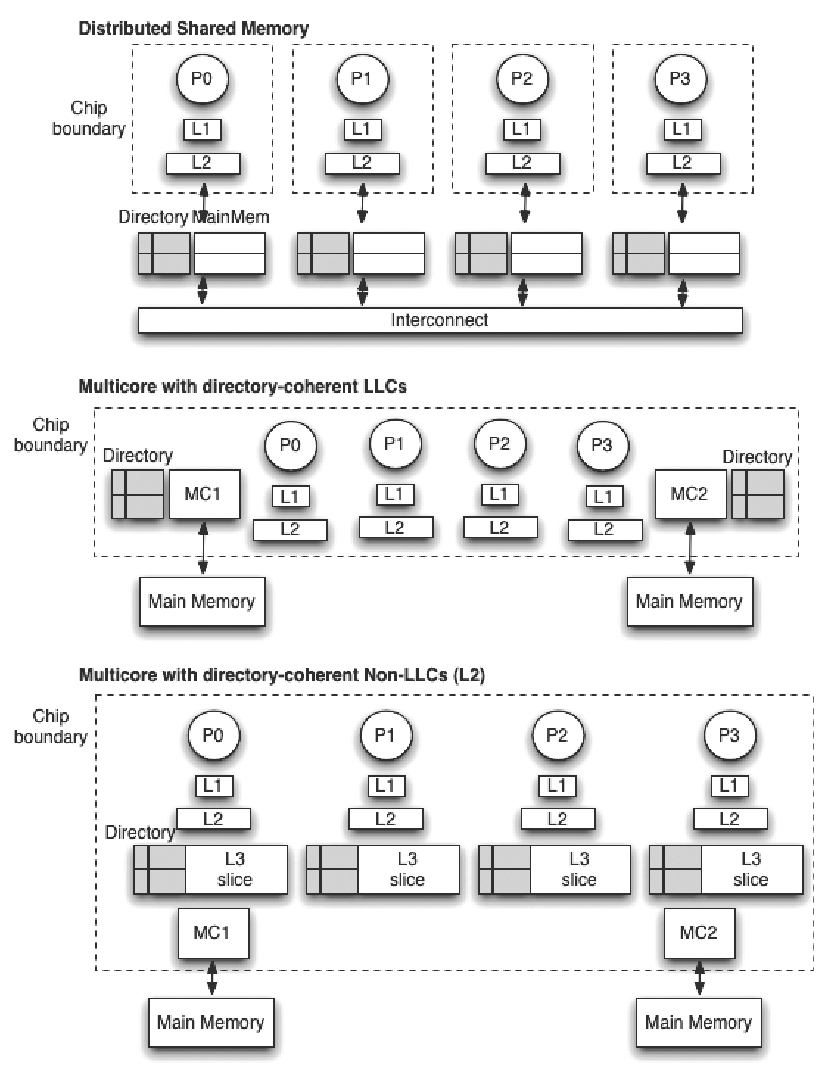

Centralized Vs Distributed Configuration

A centralized directory is simple to design. However, anything centralized at some point becomes a bottleneck to scalability: all cache miss requests will go to the same place and all invalidations have to be sent out from the same place. Thus, a scalable implementation of a directory requires a distributed organization.

Example: Possible Directory Locations

Implementation Correctness and Race Conditions

Previous discussions have assumed that:

- the directory state and its sharing vector reflects the most up to date state in which the block is cached

- messages due to a request are processed atomically (without being overlapped with one another)

In real systems, both assumptions do not necessarily apply. This results in various protocol races that need to be handled properly.

Out-of-Sync Directory State

Sometimes the directory having an inconsistent view of the cache states. Cache states can get out of sync is because they are not updated in lock step, and some events in the caches are never seen by the directory state.

One way to avoid this naively is to let the cache notify the directory when it is going to evict something, however, this will generate traffic, when there are a lot of eviction, the overall performance will also be reduced.

A directory state can become out-of-date if a cache line is silently evicted (e.g., due to cache replacement policies) without notifying the directory. One major situations here is that the directory thinks the block is shared / exclusively shared / modified in some node, but the node has already evicted it silently(maybe due to capacity).

Example of out-of-date information caused by silent eviction

- Initial State:

- Cache C1 and C2 hold a shared copy of a memory block

X. - The directory state for

Xis:- State: Shared

- Sharers: C1, C2

- Cache C1 and C2 hold a shared copy of a memory block

- Silent Eviction:

- Cache C2 evicts block

Xsilently (e.g., due to replacement). - The directory is not informed and still lists C2 as a sharer.

- Cache C2 evicts block

- Subsequent Operation:

- Cache C3 issues a write request to block

X. - The directory believes C1 and C2 still hold shared copies.

- Cache C3 issues a write request to block

- Protocol Action:

- The directory sends invalidation requests to C1 and C2.

- C1 invalidates its copy and acknowledges the directory.

- C2 checks its cache, finds that

Xis no longer present, and may either:- Ignore the invalidation (no action needed), or

- Respond with a "not-present" message to update the directory.

- State Update:

- The directory receives acknowledgments from all relevant caches.

- It updates the sharer list to remove C2 and marks C3 as the exclusive owner.

How to handle silent eviction

- Robust Acknowledgment Mechanism: The directory relies on acknowledgments from caches to confirm the invalidation. If a cache no longer has the block, it can signal this with a "not-present" or similar response.

- Lazy Updates: If caches do not inform the directory of silent evictions immediately, these are resolved during subsequent operations (e.g., writes or further invalidations).

- Periodic Cleanup (Optional): Some systems include mechanisms for periodic reconciliation between cache states and the directory to proactively correct stale information.

Another situation is when the directory thinks a node is already a sharer of a block, but the directory receives a read request from the node. This situation occurs because the node that kept the block in its cache has silently evicted the block, while the directory still thinks the node is a sharer. When the node wants to read from the block, it suffers a read miss, and as a result, a read request is sent to the directory. Handling this case is also simple. The directory can reply with data to the requester and keep the sharing bit vector unchanged, since the bit vector already refects the node as a sharer.

A Read or ReadX request may arrive at the directory from a node that the directory thinks as caching the block exclusively (in exclusive or modified state). In this case, apparently the node that owns the block has evicted the block. If the block was clean, no write back (or flush) had occurred, whereas if the block was dirty, the flush message has yet to reach the directory. The directory cannot just reply with data since it may not have the latest data. In contrast to the case in which the directory state is shared, with an EM state, the directory cannot reply with data just yet. However, it cannot just wait for the flushed block to arrive either because it may never come (the block might be clean and was evicted silently by the requester while it was in the exclusive state).

The question mentioned in last example is not a problem that can be solved just by the protocol at the directory alone, the coherence controller at each processor node must also participate.

When the processor evicts a dirty block and flushes the block to the main memory at the home node:

- The processor must keep track of whether the write back has been completed or not, with a structure called the outstanding transaction buffer.

- The home node must send an acknowledgment upon the receipt of a fush message.

- The coherence controller at the processor side must also delay

ReadorReadXrequests to a block that is being flushed, until it gets an acknowledgment from the directory that the flushed block has been received.

This way, the directory will never see a Read/ReadX request to a block from a node that is still flushing it.

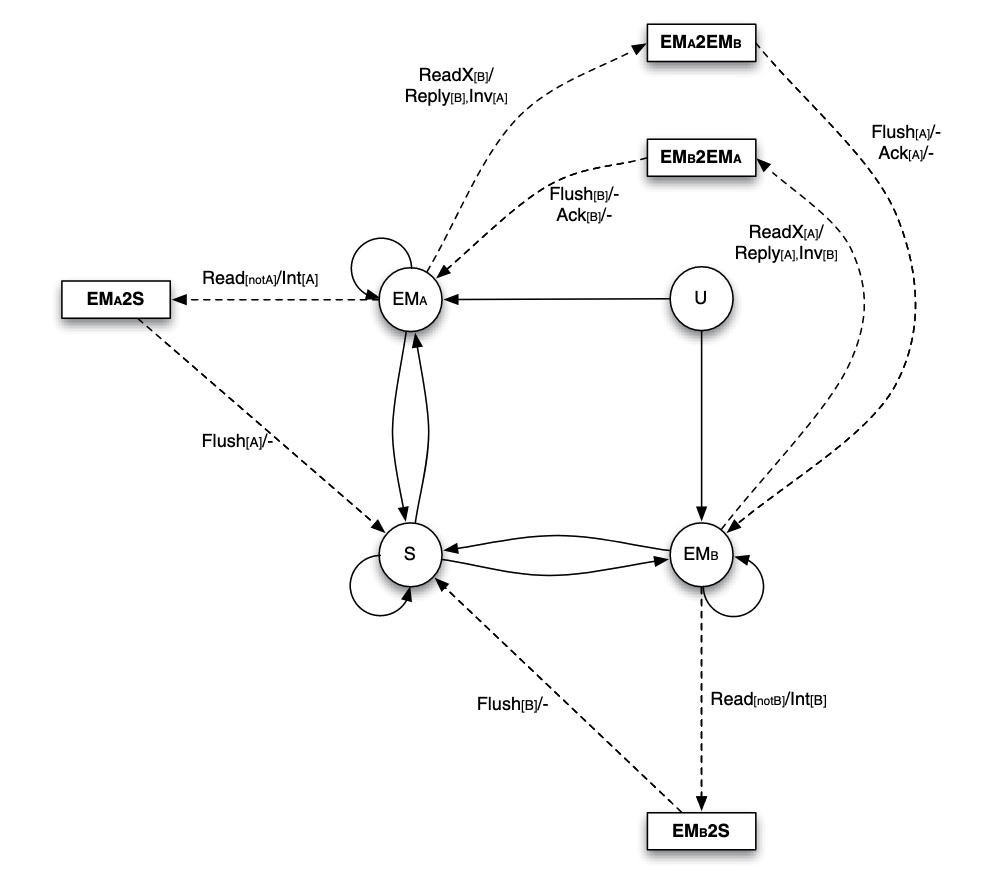

This state machine is for per entry on the directory. Recall that in full bit vector format, it means that each

In the figure,

- The left hand side of

/is the request received from the processor by the directory. The sender of the message (the requesting node) is shown in the brackets. - The right hand side of

/is the messages sent by the directory as a response to the request received from the processor. The destination of the message is shown in the brackets. - Only state transitions that are new compared with previous graph is labeled.

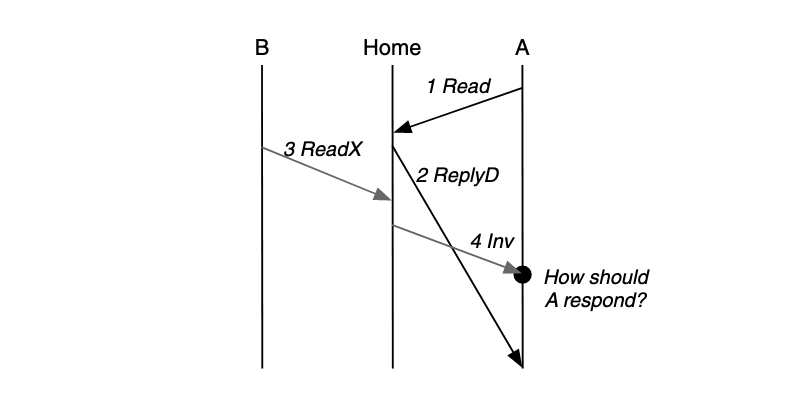

Races and Overlapping Requests

When messages that correspond to a request do not happen instantaneously, then it is possible for messages from two different requests to be overlapped.

Example: Early Invalidation Race A processor may try to read from a block and another processor may try to write to the block. Both the read and read exclusive requests to the same block may occur simultaneously in the system:

To distinguish when the processing of two requests is overlapped and when it is not, if the end time of the current request processing is greater than the start time of the next request, then their processing is overlapped; otherwise it is not.

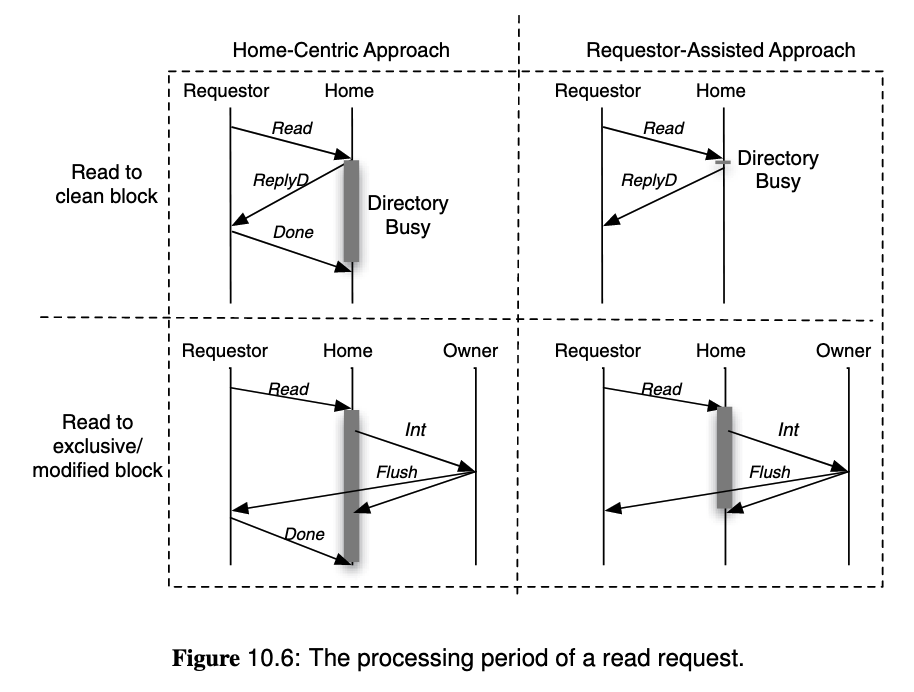

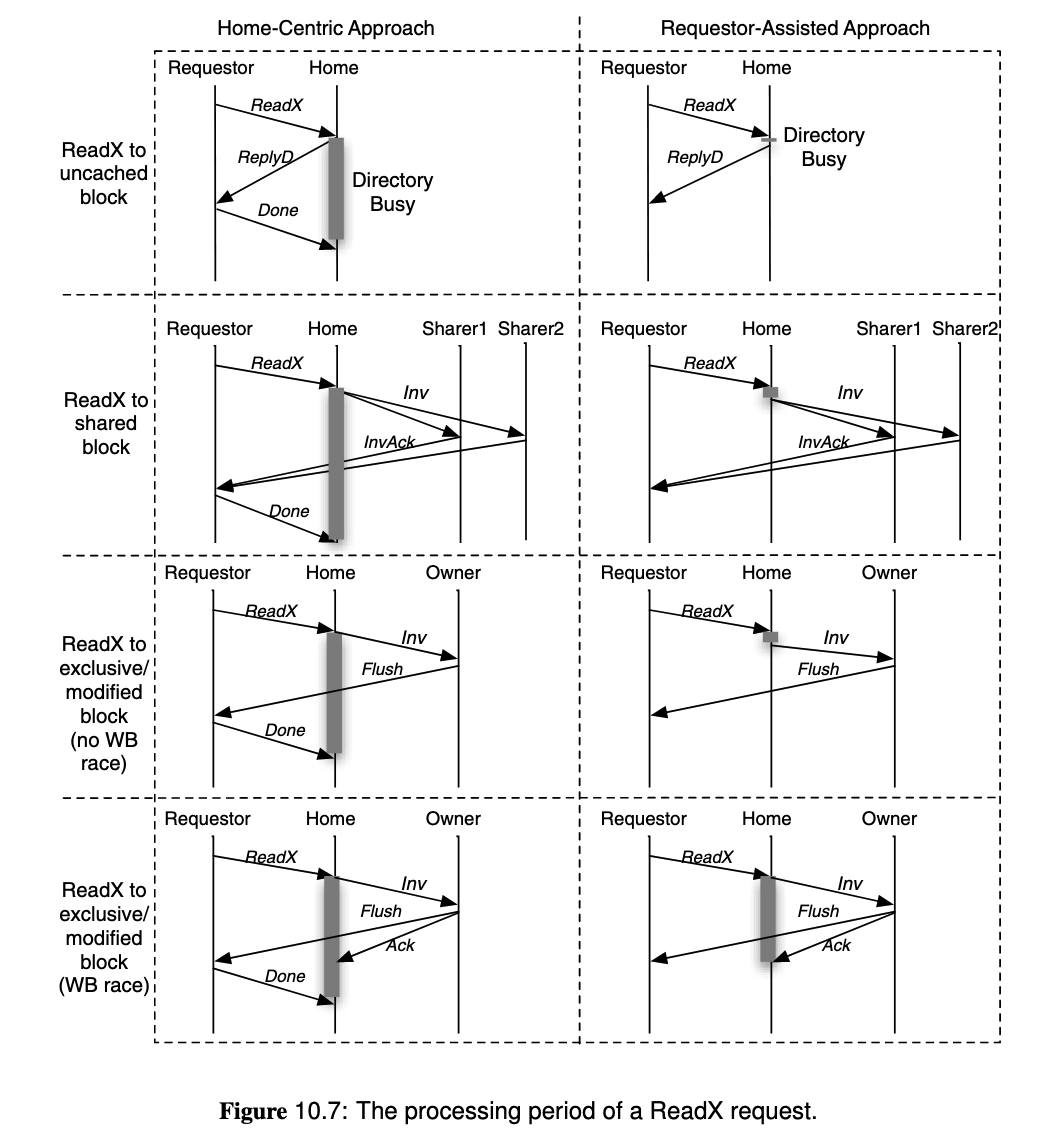

To solve overlapping requests,

- Home Centric Approach: Let the directory (home node) determine when the operation is complete, by receiving

Acks from the requester. It must defer or nack other requests to the same block before the current operation complete. - Requestor Assisted Approach: Let the cache controller to track ongoing requests, and only handle conflicting incoming requests after the request is complete. This allows the directory to finish the request earlier because it does not wait for

Ack.

A more complete directory state finite state coherence protocol diagram: