Transactional Memory

Transactional Memory

Definition: Transactional Memory Transactional memory allows a group of statements(memory operations) to be atomic and serializable without using locks. Transactional memory is:

- Atomic: either all these memory operations are performed and become visible, or none of them. A transaction is committed if its memory operations are performed.

- Serializable: global view of memory is consistent with ordering all transaction operations as a group in an interleaved serial execution of the program.

Compared to LL/SC instructions mentioned in Lecture - Consistency and Synchronization Problems which is more limited in scope but lightweight and suitable for fine-grained synchronization tasks, transactional memory offers broader support for complex atomic regions and simplifies programming.

Transactional memory operation is a code region enveloped as a transaction appears to execute fully or not at all (atomicity) without affected by interference from other threads (isolation):

| Lock | Transactional Memory |

|---|---|

|  |

From programmers' perspective, using locks requires explicit declaration, lock and release on lock variables. Transactional memory enables atomic regions in parallel software by allowing blocks of code to execute as transactions without explicit locks.

Under the programming layer, transactional memory provides:

- Speculative Execution: Transactions execute speculatively, tracking memory reads and writes in special hardware structures (e.g., cache or transactional buffers).

- Conflict Detection: The hardware monitors for conflicts (e.g., another thread modifies memory accessed by the transaction).

- Commit or Abort:

- If no conflicts occur, the transaction commits, making its updates globally visible atomically.

- If conflicts occur, the transaction aborts, and all changes are discarded, requiring retry or fallback logic.

HTM simplifies programming by avoiding manual lock management and reducing overhead for uncontested regions, but hardware resources and conflict detection limits can cause transactions to abort. A comparison between lock and HTM:

| Aspect | Transactional Memory (HTM) | LL/SC |

|---|---|---|

| Scope | Supports multiple memory locations within a transaction. | Operates on a single memory location. |

| Granularity | Detects conflicts for large memory regions using cache-line tracking. | Limited to a single address with explicit Load/Store operations. |

| Conflict Handling | Detects and handles conflicts automatically. | Relies on retries if the condition (SC succeeds) is violated. |

| Programming Model | High-level abstraction for atomic regions (e.g., transactional blocks). | Requires manual loops and retries around LL/SC operations. |

| Ease of Use | Easier for programmers; reduces explicit locking. | More low-level, requiring careful management. |

| Hardware Requirements | Requires dedicated transactional buffers or cache tracking. | Relatively simpler hardware support. |

The implementation of transactional memory can be either:

- Software Transactional Memory (STM)

- Hardware Transactional Memory (HTM)

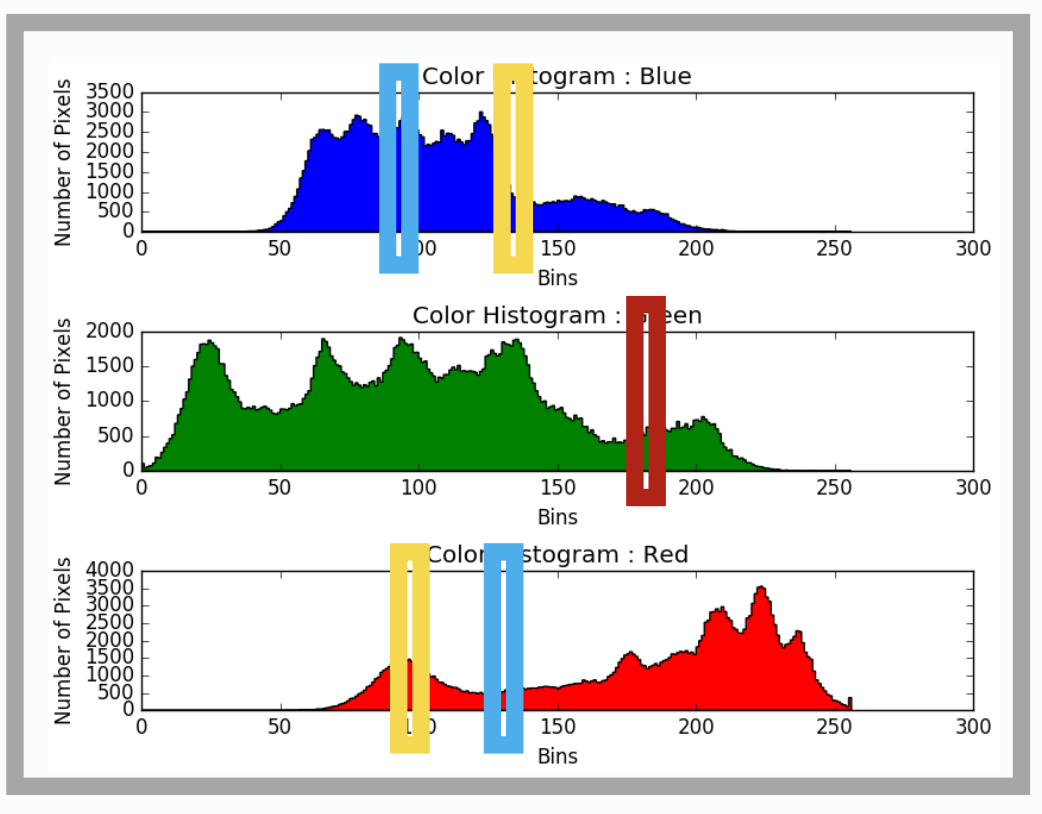

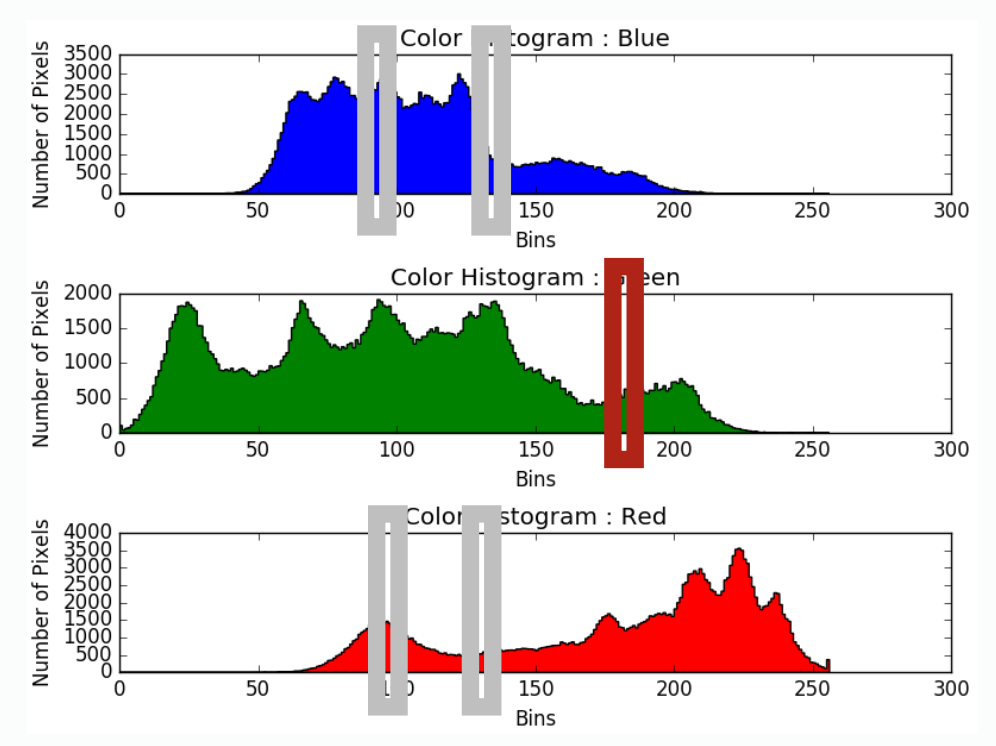

Granularity of Consistency

Transactional memory provides a different perspective on atomicity and has different view on granularity.

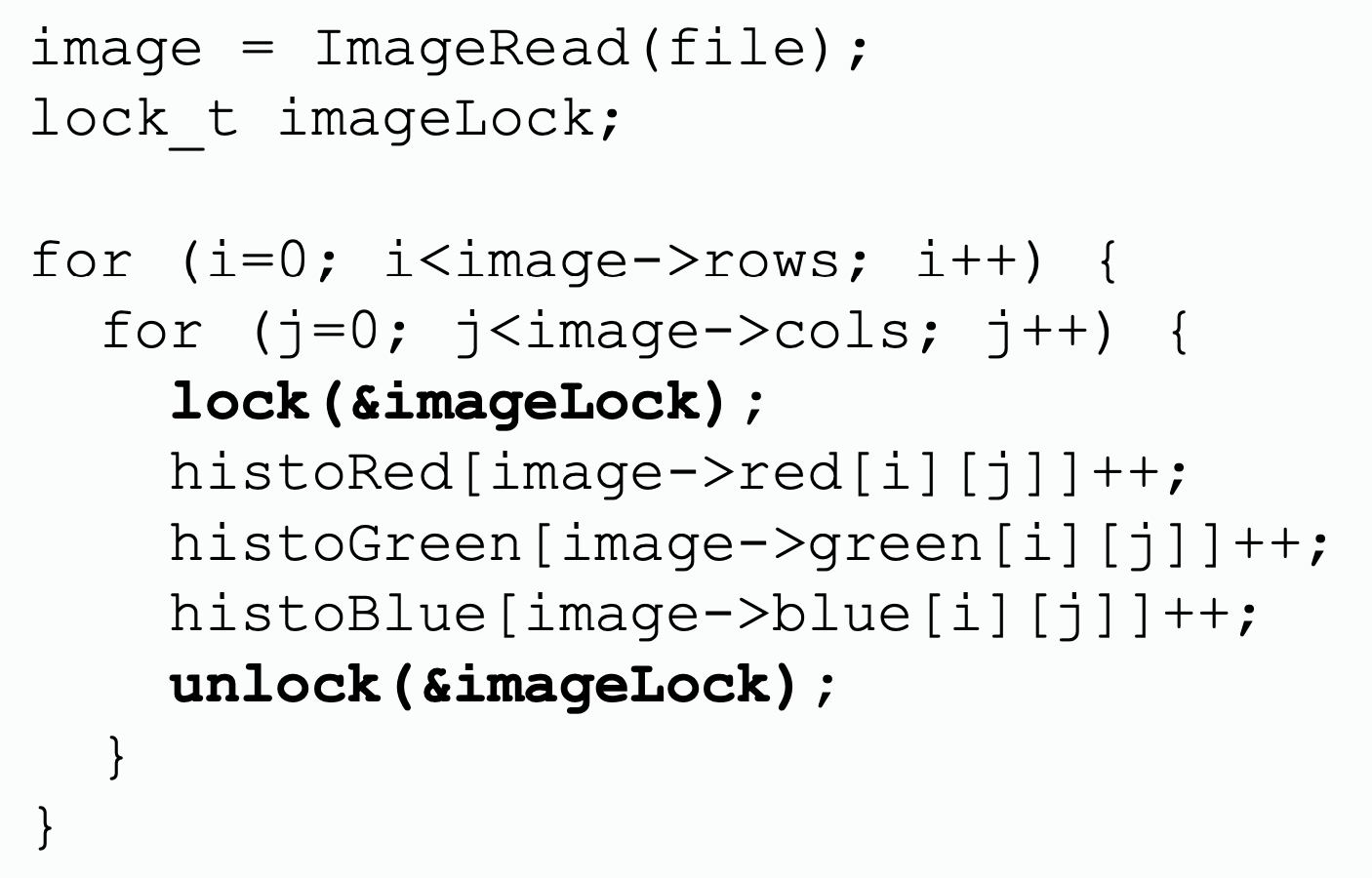

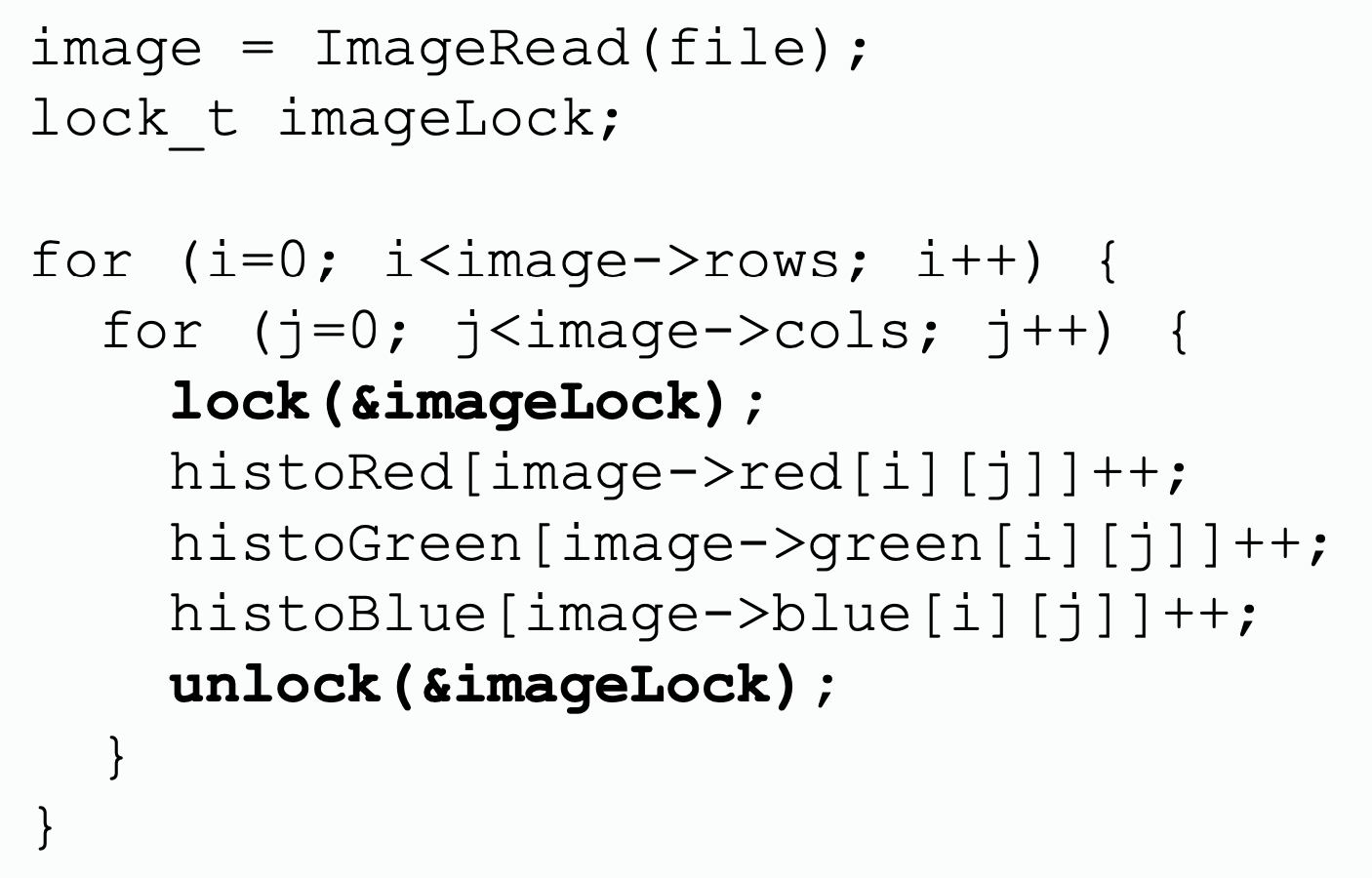

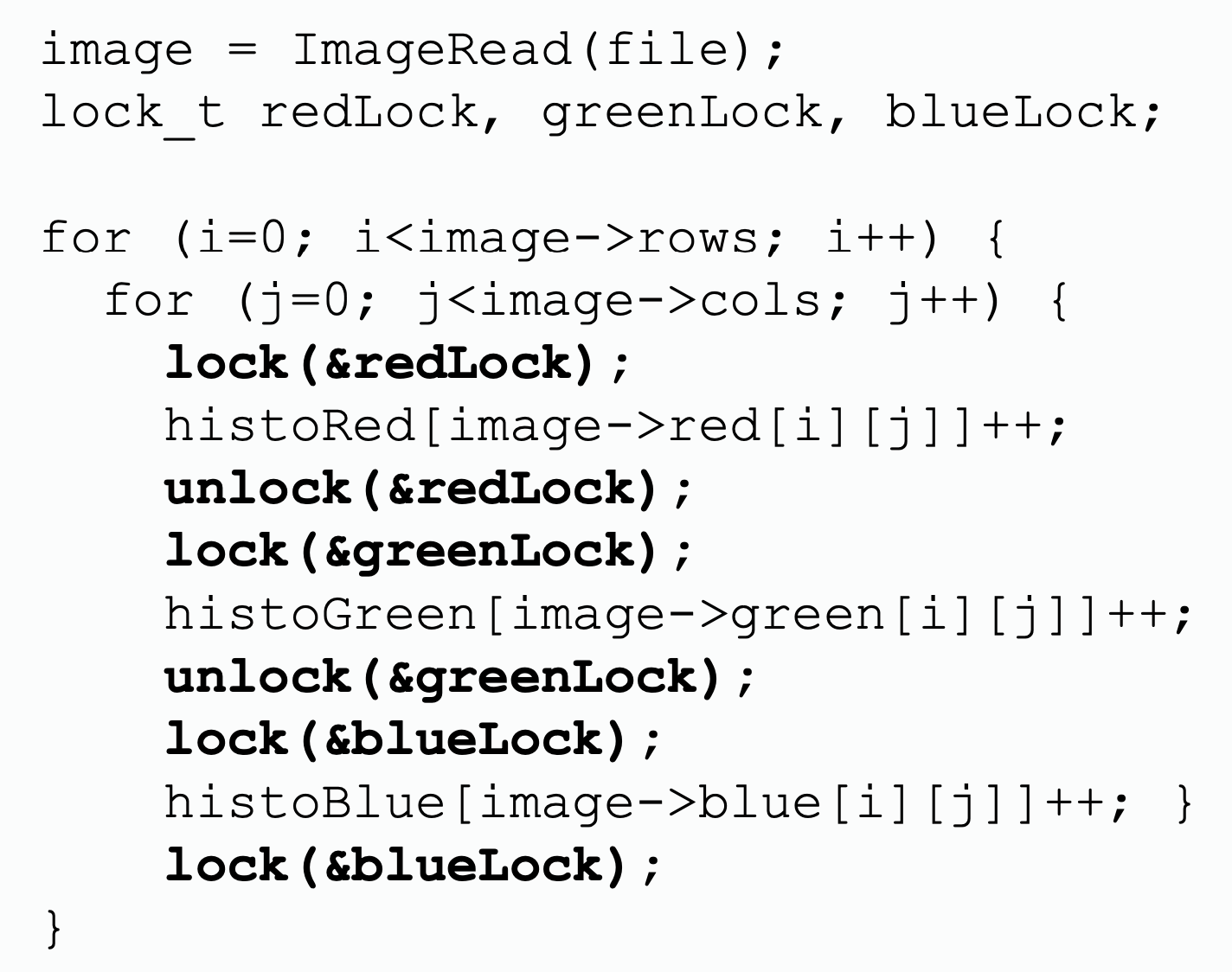

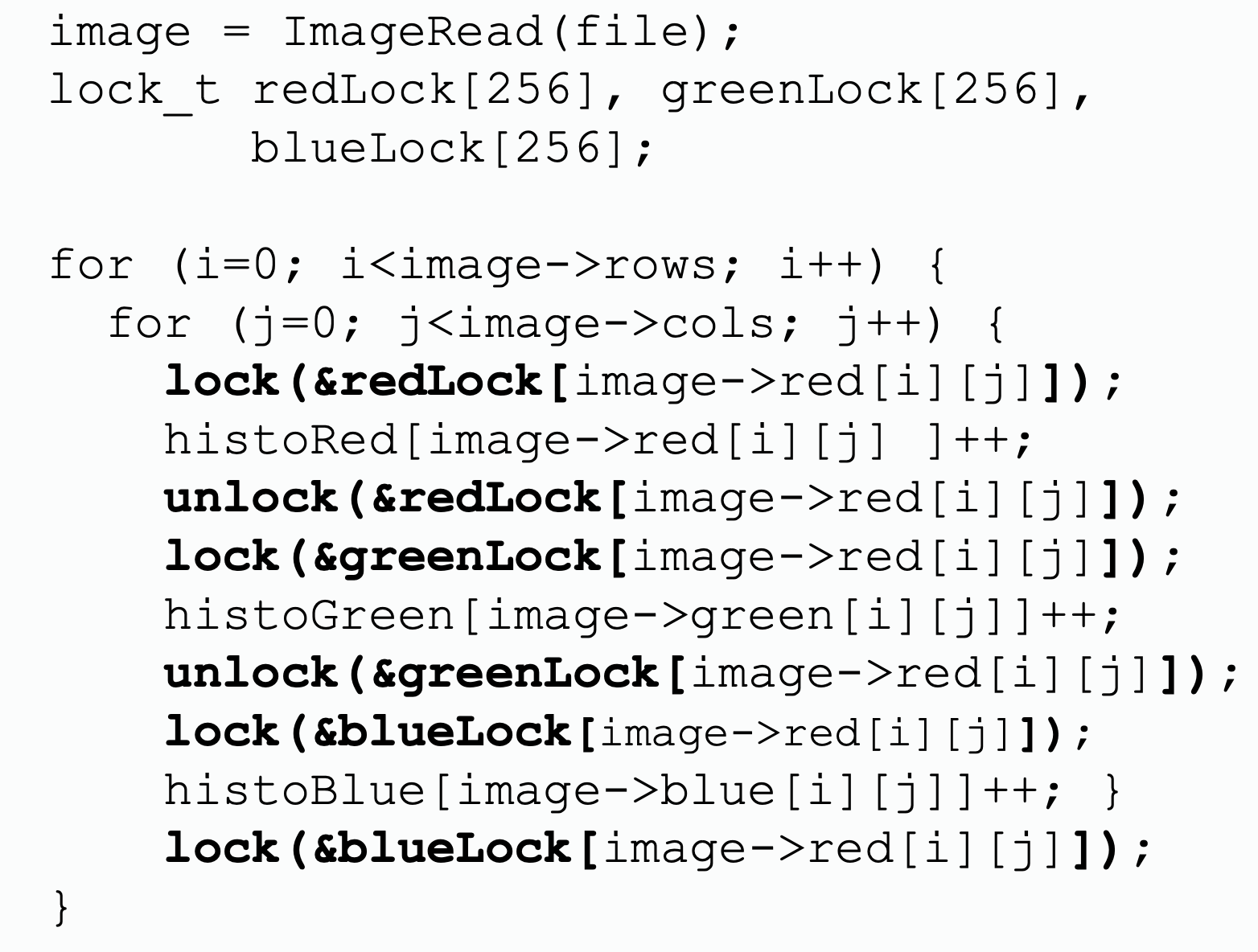

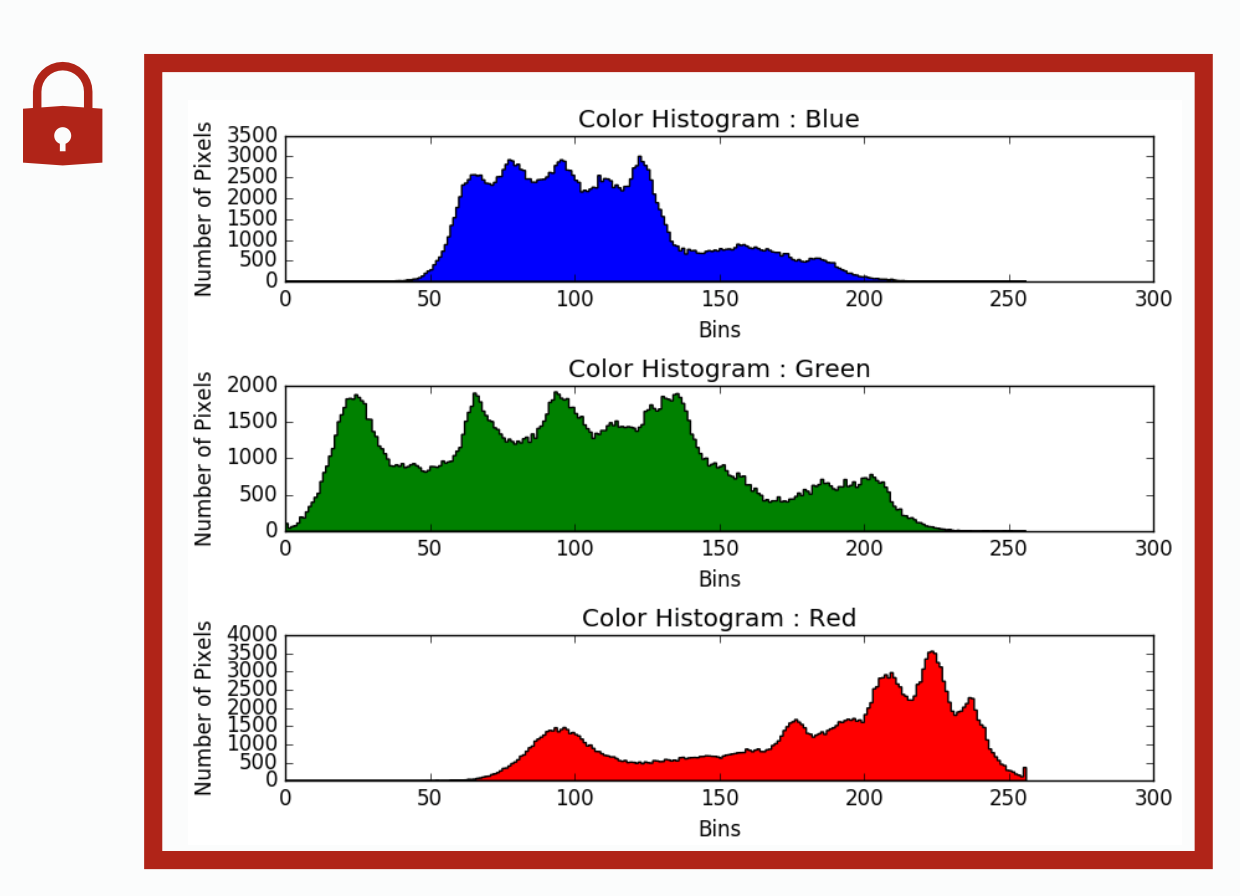

Granularity with Locks

| Coarse-grained lock | Fine-grained lock 1 | Fine-grained lock 2 |

|---|---|---|

|  |  |

|  |  |

| per histogram lock | per column lock | |

| does not expose parallelism at all, all thread will stuck at waiting others | exposes a little parallelism between operating on different diagrams | exposes a lot of parallelism by allowing writing to different column of each diagram simultenously |

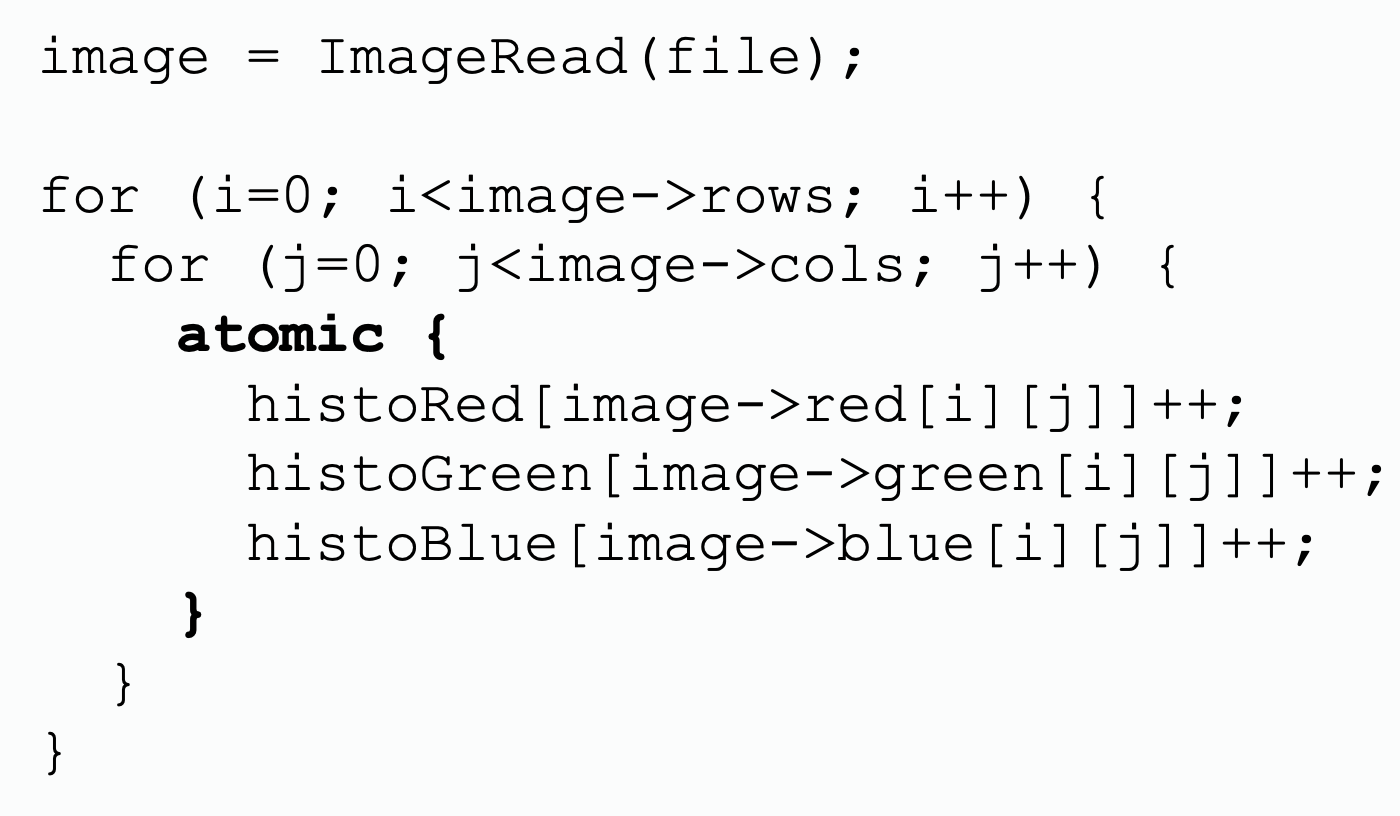

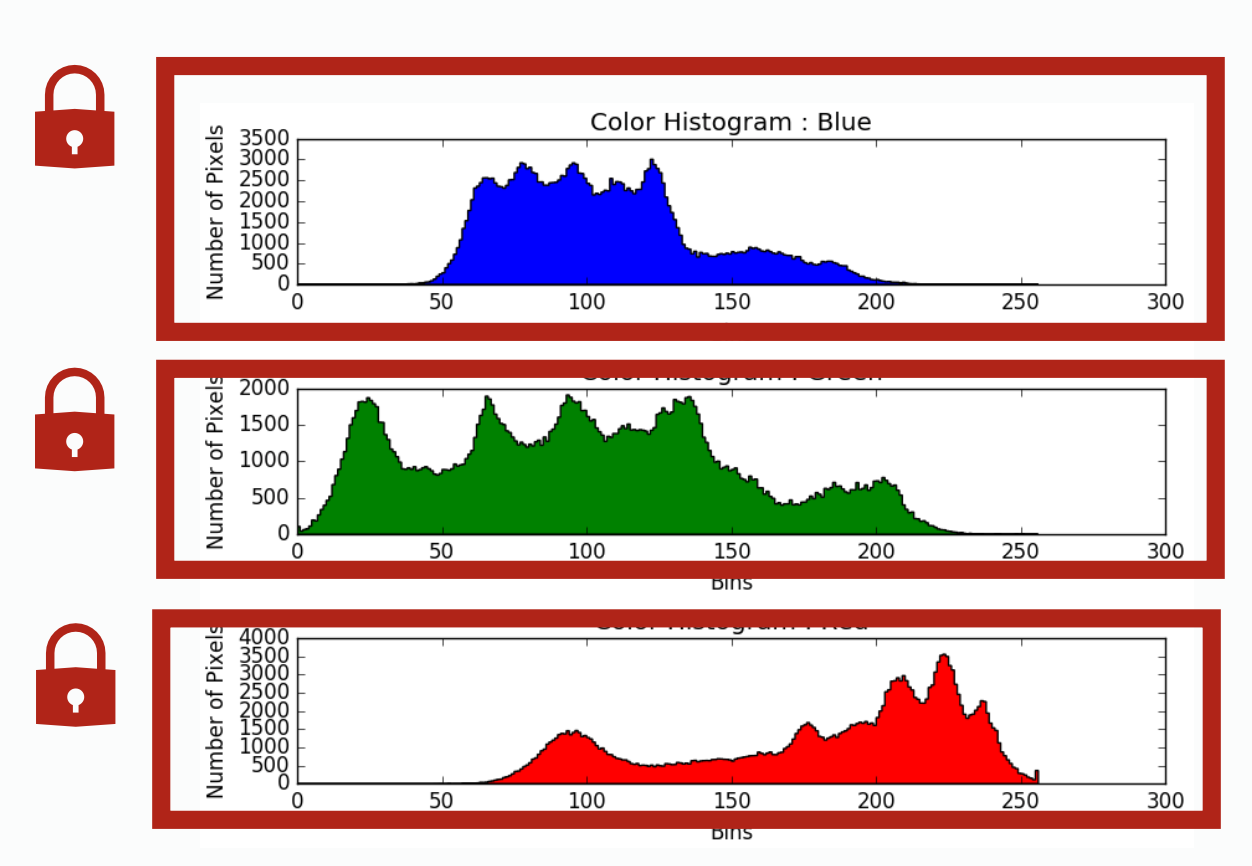

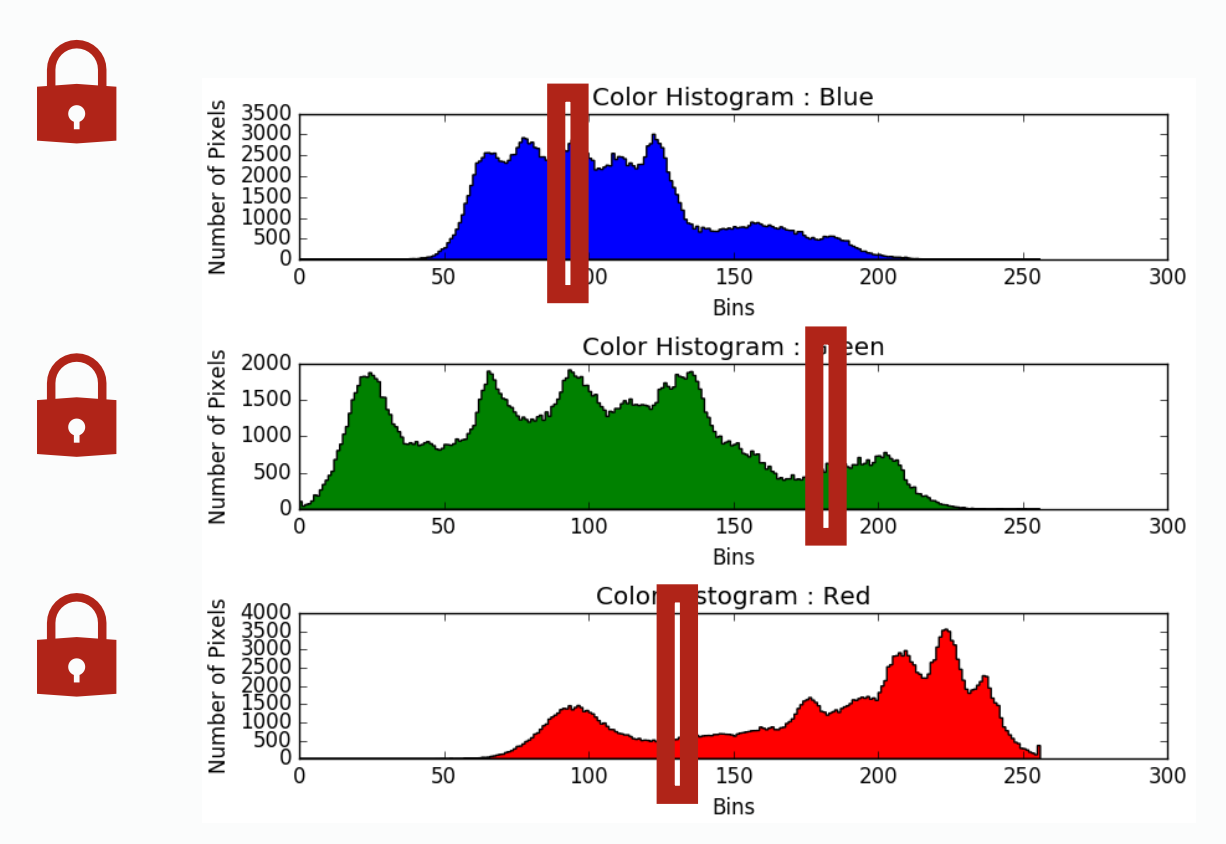

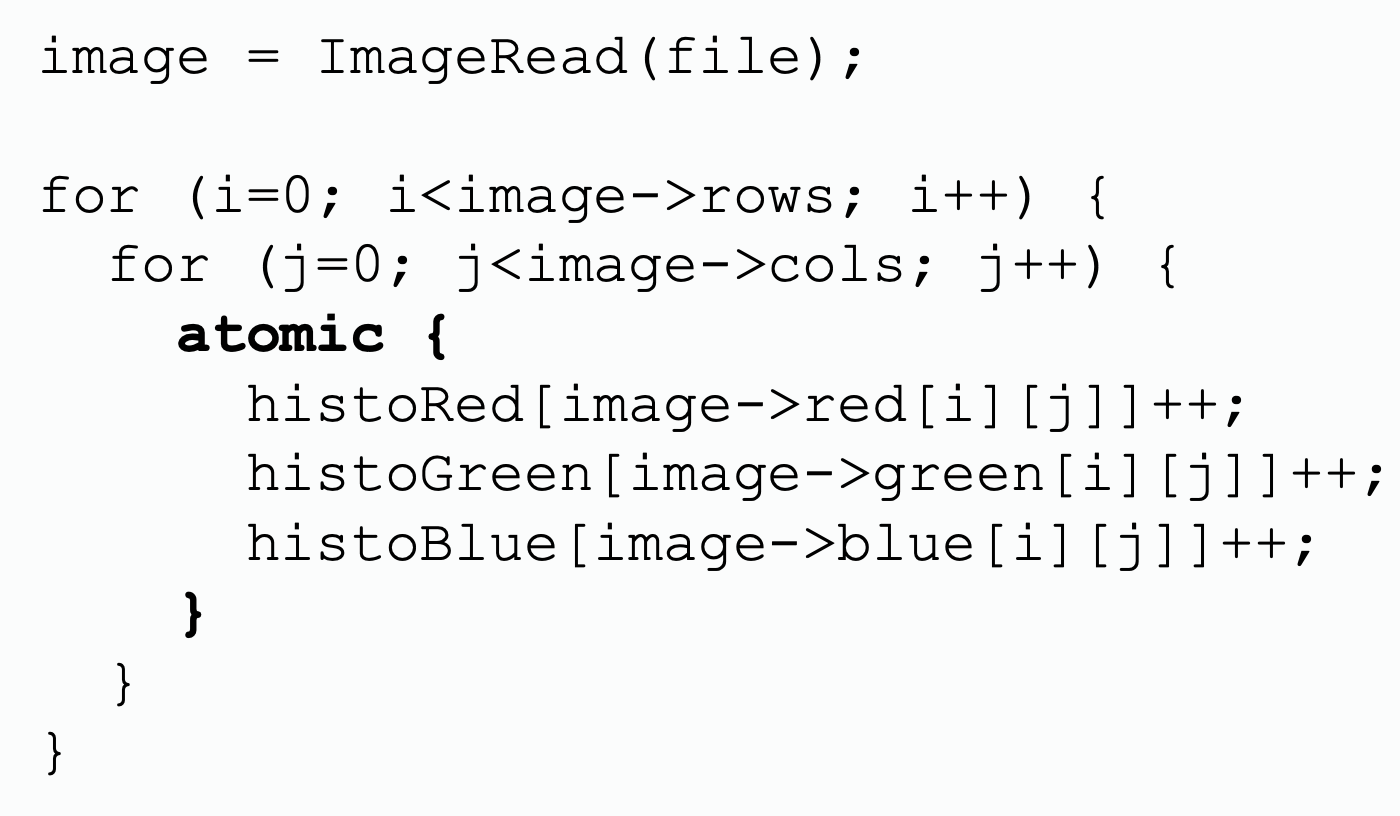

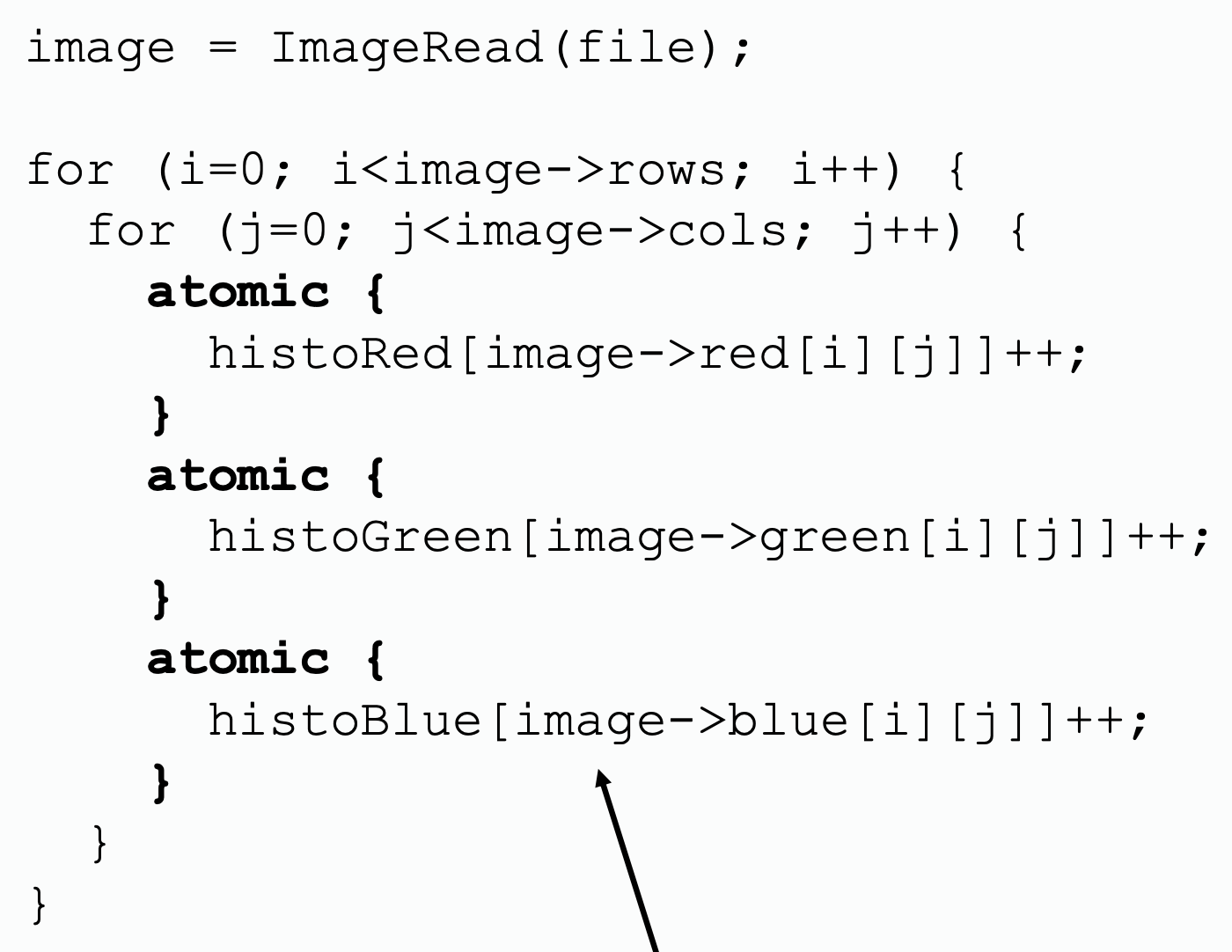

Granularity with Transactional Memory

| Coarse-grained transaction | Fine-grained transaction |

|---|---|

|  |

| This is fetch-and-increment, but transaction is more general. | |

|  |

Hardware Implementation

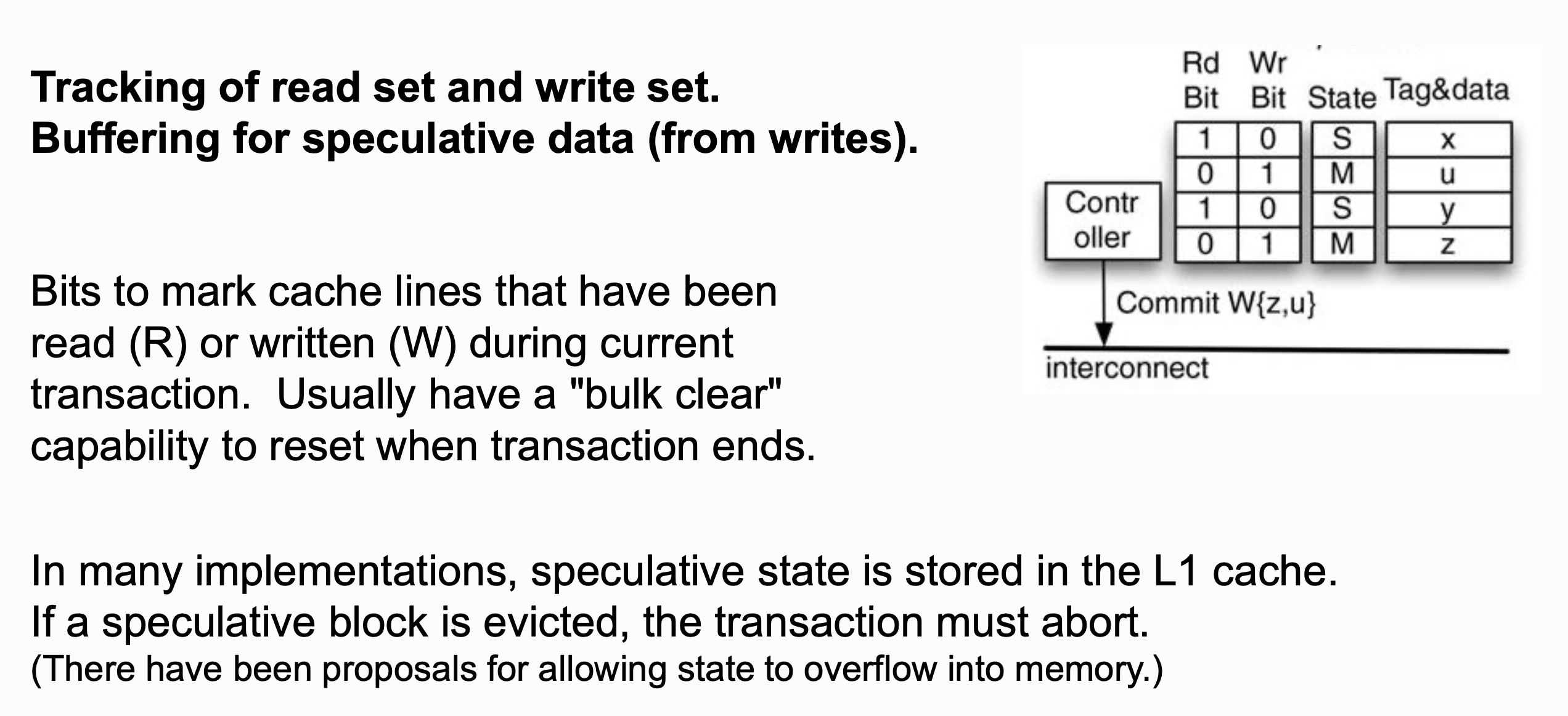

Instead of acquiring a lock, the hardware tracks memory reads and writes in the cache (or transactional buffers). Usually, hardware transactional memory marks the address as being read or written usually by adding read bit and write bit to the address.

Example: one possible implementation on hardware

Conflict Detection and Aborting

Conflict detection is naturally achieved via cache coherence protocol. In example above:

- Invalidation for a line in the read set = conflict

- Intervention/invalidation for a line in the write set = conflict

On detecting the conflict, two strategies are:

- eager: detect the conflict on the remote request happens

- lazy: only notified when commit happens

The policy of responding to a conflicts is usually:

- requester wins: Receiver of conflicting request provides data and aborts.

- requester stalls: Receiver either defers (buffers request) or NACKs (requester retries). Requester only aborts if there's a possibility of deadlock.

- committer wins: Someone commit first will win. This is compatible with lazy conflict detection.

On committing and aborting transactions:

- On aborting transaction, it can:

- simply mark all corresponding cache with

Mstate to beIstate, witch will abort all write operations to any address. - Clear R/W bits.

- Signal ABORT to processor, which must rollback execution

- simply mark all corresponding cache with

- On retry, new transaction will load non-speculative data as needed.

Consider two threads performing operations on a shared variable x using a lock.

Pseudo-Code:

Thread 1: Thread 2:

lock(L); lock(L);

x = x + 1; x = x + 2;

unlock(L); unlock(L);

- Start Transaction: Both threads detect the lock operation and treat it as a transactional start.

- Speculative Execution:

- Each thread executes the critical section speculatively.

- Hardware tracks memory operations (

xandL) in the cache.

- Conflict Detection:

- If

Thread 1writesxwhileThread 2is also accessingx, the cache coherence protocol detects the conflict.

- If

- Conflict Management:

- Abort: One thread (e.g.,

Thread 2) aborts its transaction. - Retry: The aborted thread retries, either re-entering the speculative region or falling back to the lock.

- Abort: One thread (e.g.,

The above example is a typically Speculative Lock Elision (SLE).

Speculative Lock Elision (SLE)

The lock is treated as a "version number." Instead of acquiring the lock, SLE records a snapshot of memory locations accessed during the critical section. This avoids modifying the lock's state in memory, which reduces contention.

The hardware monitors memory accesses (via cache coherence mechanisms). If another thread modifies a memory location accessed speculatively, a conflict is detected.

On a conflict, SLE aborts the speculative execution, rolls back changes, and retries execution by falling back to the traditional locking mechanism.

Transactional Lock Removal (TLR)

TLR uses transactional memory to maintain a private "working copy" of the data modified during the critical section. The actual lock is ignored during speculative execution.

Similar to SLE, TLR uses hardware mechanisms to detect conflicts through cache coherence protocols. Any write-set or read-set conflict triggers detection.

On a conflict, TLR aborts the transaction and retries execution, potentially reverting to locking. It ensures that only one thread makes forward progress in case of contention.

How SLE and TLR Address Bottlenecks

- Avoid Overhead: By avoiding actual lock acquisition, both techniques reduce memory contention and cache invalidation associated with locks.

- Conflict Resolution: They rely on hardware's ability to detect conflicts at fine granularity, leading to more efficient resolution than traditional lock contention.

- Scalability: Both improve scalability in multi-core systems by reducing the serialization imposed by locks.

| Feature | Speculative Lock Elision (SLE) | Transactional Lock Removal (TLR) | Locks |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lock Interpretation | Ignores lock but speculates mutual exclusion | Ignores lock entirely; full transactional semantics | Strictly acquires and releases lock to ensure mutual exclusion |

| Fallback Mechanism | Acquires the lock on abort | Retries transaction or falls back to lock | - |

| Assumptions | Assumes lock is not critical for logic | Assumes critical section can complete without conflict | Assumes critical section needs strict serialized access |

| Conflict Detection | Hardware-monitored via cache coherence | Hardware-monitored via cache coherence | No explicit conflict detection, contention leads to blocking or spinning |

| Conflict Management | Aborts and retries with locking | Aborts and retries transaction or locks | Threads wait |

| Version Control | Implicit (speculative snapshots of memory) | Maintained via transactional memory | Explicit |

| Performance Overhead | Low unless conflicts occur frequently | Low unless conflicts occur frequently | High under contention (due to lock contention and thread blocking) |

| Scalability | High for low-conflict scenarios | High for low-conflict scenarios | Poor scalability under high contention |